Content Warning: Matias Sosa-Wheelock’s death affected all members of the campus community differently, depending on individual experiences that night, in the days following or with mental health and mental healthcare at other points in their lives. This special report includes in-depth reporting on the response to Sosa-Wheelock’s death as well as the state of mental health and healthcare on campus more broadly. While we have refrained from including graphic details, it may nonetheless be difficult to read. Before beginning, please be aware.

For a list of support resources on and off campus, visit this page.

On Sunday, April 8, as part of their annual “Macalester Sunday” program, President Brian Rosenberg spoke to the congregation at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Minneapolis.

Rosenberg focused his remarks on his perception of the societal pressures and related mental health challenges facing young people.

Colleges, he said, “were never designed to be mental health providers.”

But, increasingly, they have needed to be. As students’ mental health concerns and mental illnesses have grown exponentially over the last ten to twenty years, demand for the support services provided by the Laurie Hamre Health and Wellness Center (HWC) has become a focus of many on campus.

Students have long questioned the efficacy of the center’s programming and service offerings, while staffers and administrators seek to strike a balance between satisfying these needs while attending to the college’s finances.

Health and Wellness

When National Alliance on Mental Illness Minnesota director Sue Abderholden ’76 was a student at Macalester, she remembers a school with minimal infrastructure to help students with basic medical needs – let alone mental health concerns.

“I think there was a small clinic,” Abderholden said. “It was right on the corner of Snelling and Grand, and you could go see if you had mono or something like that. I was never aware that they were doing any mental health services there, and I think that was true of most colleges back then. They just threw you to the wolves.”

Today, the HWC strives to create community and promote health, by combining medical services and educational programming with mental health support and counseling services. The goal is to care for the student as a whole.

“It’s a wellness center by intention,” Vice President for Student Affairs Donna Lee said, “I think there’s something powerful in having the Wellness Center [and] not a separate counseling center like a lot of campuses have.”

Perception of HWC

Leah Wilcox ’18, chair of Macalester’s Disability, Chronic Pain and Chronic Illness Collective, sought out therapy at the HWC. She was later directed off-campus to a specialist, but retained a positive impression of the center.

“I’d say the Health and Wellness Center counseling is counseling, and the off-campus therapy is therapy,” Wilcox explained. “I found [the HWC] extremely useful, and also different than my experience with therapy off-campus.”

“I think Health and Wellness does the best that they can,” Voices on Mental Health co-chair Kendall Dickinson ’18 said. “They market self care and mental healthcare to students in a broad sense.”

Despite its best intentions, the center doesn’t have an entirely positive reputation among the student body. Some students question the surface-level quality of some of the HWC’s programs, which have in the past included sponsoring massage chairs in the library and nap locations around campus, alongside more extensive medical offerings.

“They do practice a different kind of therapy there. It’s more short term, less about digging into things sometimes,” Wilcox said.

Dickinson recognizes that some of this outreach can be effective in reaching pockets of the campus community that might not otherwise choose to engage with the HWC themselves. “Things like mindfulness, meditation, those sorts of buzzwords that aren’t stigmatized, is a good way to reach out to people,” Dickinson said. “But I [also] think that isn’t specific enough.” Liz Roten ’18 agreed with Wilcox’s assessment of the HWC’s counseling practices.

“I think it’s kind of hard to tell where Health and Wellness’ priorities are,” she said. “It seems kind of like they’re trying to reach more people in a more superficial way than having really hard conversations with individual students.”

A significant issue that students face is an unclear understanding of who they should contact at the administrative level if they are dealing with mental health challenges.

“A lot of times when [I’ve been concerned about a friend], I will call my own therapist back home,” Anni Clark ’21, a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual violence said. “But in terms of on-campus resources, I really don’t know who I would go to.” Oftentimes that means that students don’t turn to the administration at all – instead looking to different, non-medical communities for support. One of the places where students frequently seek help for their mental health issues is the Center for Religious and Spiritual Life (CRSL), or their own existing support networks.

“Everyone in the athletic department has been really great and supportive, but the rest of the administration will be like ‘oh, yeah, look, we’ll look into it,’ and then nothing happens,” said Will DeBruin ’20, a football player and first responder at the scene of Sosa-Wheelock’s death in February.

Liz Roten ’18 gained an advocate in Disability Services.

“[Former Disability Services Director Robin Hart Ruthenbeck] was aware that I was not doing well, I was self-harming again and was isolating – that I really was on a downhill slope,” Roten said of her sophomore year. “I had her personal cell phone number. So when shit really hit the fan I called her, and Robin also connected with my therapist off campus. So there was also that kind of external accountability. It prevented anything from going too far.”

But while advocates like Ruthenbeck can be helpful to students in need, they are often not medical professionals – limiting the kind of care they can provide.

Student frustrations regarding the HWC also stem from the limits on appointments and other barriers to receiving the care that they need. Every student gets 10 free counseling sessions per academic year, but many feel that this number is insufficient. Wait times for counseling sessions also represent a considerable problem for students trying to get support.

When HWC Director Denise Ward last conducted a study on the center’s wait times, students waited an average of 10 days before getting an initial consultation. While some students were seen quickly, others had to wait for up to three weeks before they could get in.

“I had a friend last semester who went [to the HWC] and was thinking about dying,” Clark said. “She went and was like, ‘Hey, I need to see a therapist,’ and they were like, ‘Okay, we’ll see you in three weeks for a consultation.’

“That’s not acceptable. It’s a hard thing to do, anyways, to say, ‘Hey, I need a therapist.’ It’s even harder to do that and be told you have to wait.”

Both Ward and Director of Counseling Ted Rueff have stated that students who are in desperate need of seeing someone will be attended to immediately and special drop-in sessions are available daily on a first-come, first-serve basis.

Nevertheless, the wait list remains a deterrent for students who are deciding whether to seek mental health support.

Much of the criticism surrounding the HWC and its ability to best serve students takes into account the larger issue of funding and resource allocation.

“I’m confused by [the HWC], because it seems like they have good intentions,” Margaret Moran ’21 said. “But…they lack the resources they need in order to be an actual source of support.”

Onur Unal ’18 was diagnosed with depression after a professor at Macalester directed him to the HWC. He had one or two of his 10 free sessions left during the semester he was diagnosed, but voluntarily put an end to the consultations because he had started to feel better. “I didn’t want to take someone else’s place, because I know how tight it is,” Unal said.

Because he had to take time off to care for his mental health, Unal will have taken two and a half extra years to graduate from Macalester, when he does so next December. “The Health and Wellness Center has too few counselors. “So it’s hard to get a spot. I mean, it’s a funding issue,” Unal said.

Students aren’t the only ones taking stock of the impact of funding and resource limitations.

“We have students in crisis,” religious studies professor Erik Davis ’96 said. “We attempt to create supports for students in crisis. There are not enough supports for students in crisis. Therefore, students remain in crisis.”

“Some people might say, ‘well, [mental healthcare is] not Macalester’s job, we’re educators.’ Okay. I get that,” he continued. “But then how are we going to deal with the sense of crisis and the fact that there are students in crisis? We have choices to make.”

Unaddressed needs

Besides the need for additional counselors and increased access to counseling, some students feel other additions could bolster the center’s goal of supporting students who have mental health concerns.

Roten argued that there is a need for Macalester to employ a full-time psychiatrist who would be able to write prescriptions for students.

While Dr. Rich Levine is currently available for student contact hours in the HWC, he is hired as a consultant psychiatrist and is rarely at the school.

“Most people don’t know that we have [a psychiatrist] because we basically don’t,” Roten said. “[Levine] is on campus once a month for half a day. And you can’t make an appointment with him unless you’ve already had a counseling appointment.” Sessions with Levine, who also consults for Hamline and practices as an emergency medicine physician at the University of Minnesota, are also capped at three per year before students are directed off campus.

Roten and others noted the importance of easing the transition for students who need to be connected with off-campus resources.

“We could have a more solid system for giving a warm transfer as opposed to ‘here’s a list,’” she said.

“Their [referral] list was not super useful for me,” Wilcox said. “A lot of the therapists were full up when I called them. It was very discouraging to just have a string of people who were already full.”

The energy required to seek professional and other help for mental health issues represents an obstacle for many students who could use it. For international students, there is the added barrier of having to work within a culturally unfamiliar environment surrounding mental health and health care.

Malvika Shankar ’19, who is currently taking a semester off, felt that the HWC’s intake process lacked the humanity that is present in her care in India.

“As an international student, the whole bureaucratisation of all forms of healthcare, physical or mental, creates a daunting and formal atmosphere,” Shankar said. “When I considered speaking to a counselor, the form-filling process put me off and I left it halfway.”

Francis Ma ’21, did not seek out the HWC when he struggled through his first semester at Mac.

“I mean there are some resources,” Ma acknowledges, “But none of them actually really understand what it means to be in a totally different country. You know, the best thing Macalester can do is try to be a home to everyone.”

Biology professor Devavani Chatterjea has seen her students struggle with mental healthcare because of cultural differences first-hand.

“[Let’s think about] whether there are structures that could be set up to help international students overcome these barriers and access health,” Chatterjea said.

The budget

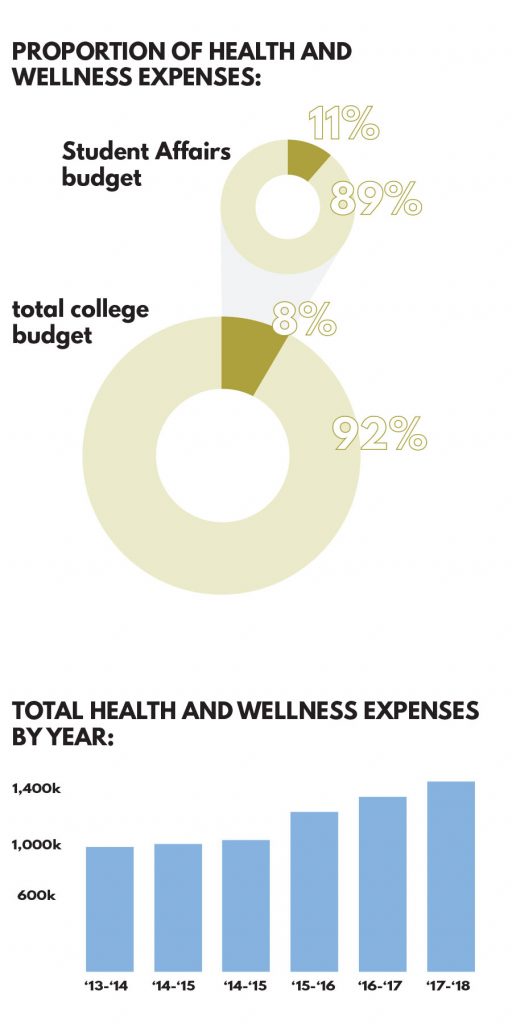

Over the last five fiscal years, the HWC has received incremental increases in funding.

In the 2012-13 year, the HWC’s total expenses amounted to $951,232. The estimates for 2017-18, place the HWC’s total expenses at $1,451,889 – an increase of 53 percent when compared to the 2012-13 year, with much of the increased spending going towards compensation and benefits for new staff.

This budget allocation amounts to 11 percent of the Student Affairs department budget, which itself represents just eight percent of the college’s expenses per year.

“I think we could always use more [resources],” Ward said. “That being said, the college has really listened to some of the needs we have around staffing.”

In 2006, the HWC as a whole had 11 staff members. Currently, the center has 23 staff members, increasing by 40 percent its capacity for student contact hours.

In counseling specifically, two full-time counselors were added since 2006 – bringing the current number of full-time counselors to six.

To Ward, the HWC’s biggest current staffing need is now on the promotional side.

“I think in terms of counseling we are getting there, [but health promotions] is about, how do we work with faculty to change expectations around deadlines or absences? How do we create living environments that provide spaces for people and opportunities to help reduce stress and anxiety? To me, that’s one of the next big pieces. You can put your fingers in the dike, but at some point you need to deal with water level.”

Programming and development

Several HWC services and programs rolled out in the last several years have begun to make a positive impact. The HWC’s intake process has been sharpened to identify from the first point of contact, the best resources to direct students towards.

Last summer, the HWC hired Julia Hutchinson – a new care coordinator who does initial consults with all students who are, in Rueff’s words, “newly presenting” at counseling services. After a roughly 20 minute-long assessment, Hutchinson funnels students to the right care modality.

“In the past, people would simply come in and be assigned a counselor when that wasn’t necessarily the best fit for them,” Rueff said. “Maybe a group is the best fit. Maybe a drop-in situation would be better. Maybe they need to be seen by Disability Services and really [don’t] need the services of an individual counselor.”

“That’s freed us up to then see other people who might have been on a waitlist before,” he continued, “and get people the kind of attention that they need and deserve in the moment.”

While Rueff said he would like to eventually see the waitlist for counseling appointments disappear entirely, he said that wait times are “trending well.”

Around 20 students remain on the waitlist for counseling services, but Ward said that most of these students are waiting on a specific counselor or time slot that may not be immediately available. Based on a student interest in peer-centered spaces, the HWC has increased its group counseling offerings significantly in the last year. The HWC currently offers seven groups, each of which addresses different health issues from: anxiety management to depression.

MCSG Community Engagement Officer Meera Singh ’19, who is organizing a panel on mental health for next fall, believes that groups can support students in ways one-on-one counseling cannot.

“Personally what’s really helpful is recognition – so having groups is really helpful to just get your troubles validated,” Singh said.

Assistant Vice President and Dean of Students DeMethra LaSha Bradley said that she is committed to creating and enhancing collective spaces on campus to promote conversations around mental health.

“In working with students, we realized many of them want and benefit from group interaction,” Bradley said. “Be that in addition to an individualized counseling appointment, or they may just want to be in community with others who have had experiences [similar to theirs] and also have that group guided by a clinician.”

Other new resources have been helpful in providing students access to clinicians and other mental health resources.

Last year the HWC hired a sports psychologist to cater specifically to the mental health needs of student-athletes. A dialectical behavioral therapist was also added to help students cope with anxiety, stress and other mental health struggles, a resource Dickinson has found very useful.

Press 2, an all-hours program which connects students with a mental health counselor over the phone, has also been effective. In the last twelve months, it has connected 186 callers with medical or psychological professionals.

“It has been very successful,” Ward said. “Two of the calls generated involved suicide gestures. The students were talking with the protocol folks and they called security and the [Residence] Hall Director on duty and were able to get to a safe space and place.”

Students can now also take Uber rides to and from their off-campus appointments, free of charge, in an effort by the HWC to help students get the care they need beyond campus.

“In the past, the college had offered taxi rides for students,” Ward in an email to The Mac Weekly. “Four years ago Health and Wellness picked up the cost for those rides [that used to be billed to a student’s account]. But the taxis took forever to come and the billing structure was problematic.”

Voices on Mental Health co-chair Tess Huber ’18, who has had to make several trips to urgent care during her time at the college, knows that this initiative can make a difference for students under financial pressure.

“There [are] times when I have the money for an Uber, and times when I have no money,” Huber said. “Like, right now, I could not afford an Uber if I needed one. This kind of thing, to make things truly accessible, is what we need to see happen.”

Rueff, on the whole, is both encouraged by and proud of the progress that the HWC is making.

“I do think, in a lot of ways, [that] Macalester is on the cutting edge of service provision for students with mental health [concerns],” he said. “I really do. I attend all the national conferences, I do all the reading, I’m well-versed in what’s going on at other places… I’m really excited about what we’ve been doing.”

Looking forward

As the HWC takes stock of its service offerings and students’ suggestions and frustrations, Ward and Rueff are planning ahead. “People need to be working upstream, so to speak, getting ahead of situations before they develop and promoting an ethos of wellbeing on the campus,” Rueff said.

Ward and Rueff have been thinking of partnering with online cognitive therapy based platforms such as SilverCloud or Learn to Live, to provide students with tools that they could use to work remotely on their therapy or more general care.

“These aren’t designed for major depressive disorders or more higher-level, more challenging mental health concerns,” Ward said. “These become resources that students can use that aren’t dependent upon an individual therapist.”

“I do think that the way people are interfacing with technology is that some people will prefer to use it, and I do think that it does augment the relationship piece that happens in a counseling session,” Rueff said.

“If I have to spend less time teaching skills in a counseling session, because I have the option to assign that as homework in an online version,” he continued, “I think [that] is to the benefit of the counseling relationship.”

If they are included in the HWC’s offerings, the online platforms would be accessible year-round and to students abroad. According to Ward, they would also be included in Macalester’s student health insurance plan.

Rueff said that he might also consider pursuing more programming targeting sophomores and students who identify as male – two demographics at greater risk of carrying out suicidal ideation.

“Sophomore year seems to be a year that students struggle more than any others,” Rueff said. “There’s less attention given to sophomores relative to their first year experience, they have not yet necessarily affiliated strongly with a major course of study and been brought into a sense of community with fellow scholars in their discipline. It’s a bit of a strange place to occupy, I think.”

Rueff said sensibilizing men on depression and suicide is equally important.While trends show that females attempt suicide at higher rates, males do so with more lethal methods, resulting in higher death rates.

Another priority is increasing the diversity of the HWC staff.

“There are healthcare disparity outcomes among persons of color,” Rueff said. “I think that is deserving of our attention, for sure, and in fact we have partnered with the Department of Multicultural Life in starting to tackle some of that.”

Both Rueff and Ward emphasized the importance of racial, religious and national diversity in its counseling staff.

“It’s definitely a high-priority [in our hiring practices],” Ward said. “Number one is ensuring quality and professionalism. Number two is we really want students to see themselves in the staff.”

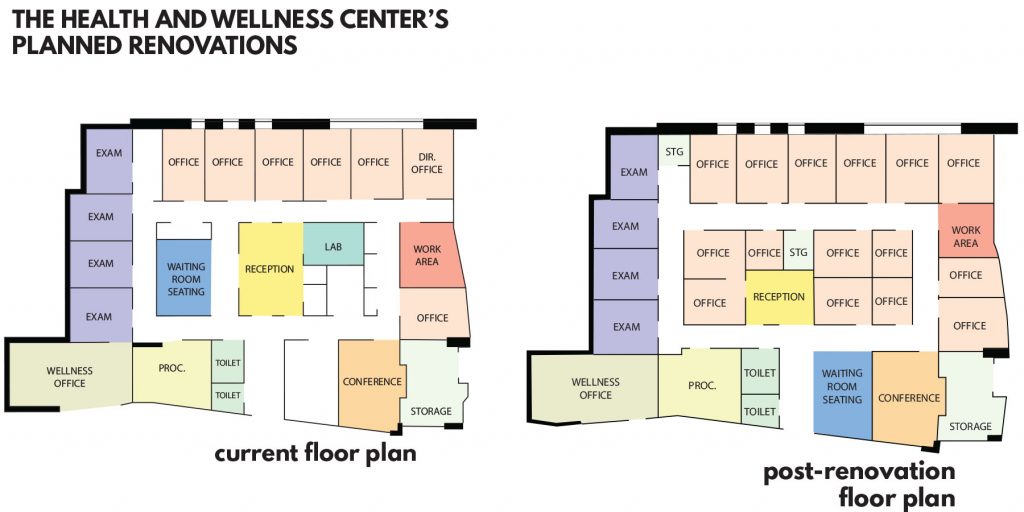

The HWC’s physical space will also be upgraded over the summer. In March, Macalester’s Board of Trustees approved the college’s budget for the 2018-19 year that includes an additional allocation for the HWC to re-work its office floor plan in the Leonard Center.

The waiting room, currently located in the middle of the center, will move to the entryway in front of the reception desk as the space currently serving as the waiting room is converted into several new offices and exam rooms.

“Really what it does is give us a space for everyone that’s here right now,” Ward said.

Denver warehousing • Sep 11, 2019 at 9:14 am

Great post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

listas iptv • Sep 10, 2019 at 7:53 am

I loved your article post.Really thank you! Want more.

junior bouncy castle • Sep 8, 2019 at 6:35 pm

Very neat post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

Harry Hamilton • Sep 8, 2019 at 5:07 pm

Hello my friend! I wish to say that this article is amazing, nice written and include approximately all important infos. I’d like to see more posts like this.

quest bars cheap • Sep 8, 2019 at 1:22 pm

Thank you for any other great article. Where else may anyone get that type of info in such a perfect method of writing?

I have a presentation subsequent week, and I am

on the look for such info.

quest bars cheap • Sep 8, 2019 at 4:28 am

I’m extremely pleased to discover this site. I wanted to thank you for ones time just for

this wonderful read!! I definitely appreciated every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new information in your web site.

quest bars cheap • Sep 7, 2019 at 10:10 pm

Greate post. Keep posting such kind of info on your page.

Im really impressed by it.

Hi there, You have performed a fantastic job. I’ll definitely

digg it and for my part recommend to my friends.

I am confident they’ll be benefited from this site.

quest bars cheap • Sep 7, 2019 at 5:13 pm

You really make it seem so easy together with your presentation but I to find this matter to be really one thing which

I feel I might by no means understand. It kind of feels too complex and

extremely broad for me. I’m having a look forward on your subsequent publish,

I’ll try to get the hold of it!

liteblue login • Sep 7, 2019 at 5:08 pm

Thank you ever so for you article post. Want more.

quest bars cheap • Sep 7, 2019 at 10:38 am

Hi there, yeah this piece of writing is truly good and

I have learned lot of things from it on the topic of blogging.

thanks.

quest bars cheap • Sep 7, 2019 at 7:53 am

Excellent blog here! Also your website loads up very fast!

What web host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host?

I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

quest bars cheap • Sep 7, 2019 at 5:12 am

excellent points altogether, you just received a emblem new

reader. What might you recommend in regards to your submit that you simply made some days in the past?

Any certain?

Home Tutor Dhanbad • Sep 6, 2019 at 2:49 pm

Great blog.Much thanks again. Will read on…

quest bars cheap • Sep 6, 2019 at 2:15 pm

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate

you penning this write-up and the rest of the website is extremely good.

big and tall recliner • Sep 5, 2019 at 11:25 pm

Thank you ever so for you blog. Keep writing.

ben wa balls • Sep 5, 2019 at 8:06 am

Im thankful for the blog.Much thanks again. Really Great.

minecraft games • Sep 5, 2019 at 5:08 am

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to protect against

hackers? I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any recommendations?

minecraft games • Sep 5, 2019 at 3:20 am

Spot on with this write-up, I seriously think this website

needs much more attention. I’ll probably be back again to read more,

thanks for the information!

stainless steel penis ring • Sep 4, 2019 at 7:16 pm

Thanks-a-mundo for the blog post.Really thank you! Awesome.

minecraft games • Sep 4, 2019 at 5:24 am

I always used to read article in news papers but now as I

am a user of internet thus from now I am using net for content, thanks to web.

minecraft games • Sep 3, 2019 at 10:49 pm

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with helpful information to

work on. You have performed an impressive activity and our whole group shall be

grateful to you.

minecraft games • Sep 3, 2019 at 12:43 pm

With havin so much written content do you ever run into any issues

of plagorism or copyright infringement? My blog has a

lot of unique content I’ve either authored myself or outsourced but it

appears a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my agreement.

Do you know any techniques to help protect against content from being ripped off?

I’d certainly appreciate it.

minecraft games • Sep 3, 2019 at 1:41 am

Do you mind if I quote a couple of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources back to your webpage?

My blog site is in the very same area of

interest as yours and my visitors would truly benefit from some

of the information you provide here. Please let me know if this okay with you.

Thank you!

Funcionamiento de aire acondicionado • Sep 2, 2019 at 4:54 pm

LG Electronics presentó muchos productos nuevos, aplicó nuevas tecnologías como los dispositivos móviles y los TV digitales en el siglo XXI y continúa reafirmando su posición como una compañía mundial. En 1997 Los primeros dispositivos móviles digitales CDMA suministrados a Ameritech y GTE en Logra la certificación UL en los Desarrolla el primer aparato IC en el mundo para DTV. Repuestos y Recambios para Repuestos – SAUNIER DUVALCompra Repuestos y Recambios para Repuestos – SAUNIER DUVAL siempre al mejor precio.

adam and eve offer codes • Sep 1, 2019 at 9:59 pm

I loved your blog article. Great.

minecraft games • Sep 1, 2019 at 1:22 pm

I am truly delighted to read this webpage posts which consists of plenty of valuable facts, thanks for providing these kinds of statistics.

HDKA 186 • Aug 31, 2019 at 10:53 pm

Im obliged for the blog.Thanks Again. Will read on…

TBF Financial reviews • Aug 30, 2019 at 10:34 pm

Very neat blog.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

vagina toys • Aug 30, 2019 at 9:40 pm

I don’t normally comment on blogs.. But nice post! I just bookmarked your site

job vacancies in nigeria for fresh graduates • Aug 30, 2019 at 8:26 am

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog.Much thanks again. Want more.

bouncy castle hire lewisham • Aug 29, 2019 at 3:42 pm

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article.Much thanks again.

bouncy castle hire and soft play in hammersmith • Aug 29, 2019 at 7:47 am

I think this is a real great article post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

bouncy castle and soft play Bexley • Aug 28, 2019 at 12:30 pm

I truly appreciate this post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

แทงบอลออนไลน์ • Aug 27, 2019 at 11:36 pm

Really informative blog.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

vegus 1168 • Aug 27, 2019 at 7:58 am

I value the blog article.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

hotmail.com login • Aug 26, 2019 at 8:50 am

Thanks for the article.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

vegus168 ไอดีไลน์ • Aug 25, 2019 at 8:52 pm

Looking forward to reading more. Great post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

yellow pages Turkey • Aug 25, 2019 at 8:52 am

A big thank you for your blog.Really thank you! Want more.

JUY-974 • Aug 25, 2019 at 12:05 am

Really informative blog. Keep writing.

quest bars cheap • Aug 24, 2019 at 9:42 am

This is really attention-grabbing, You are an excessively professional blogger.

I have joined your feed and stay up for in quest of more of your great post.

Also, I’ve shared your web site in my social networks

quest bars cheap • Aug 24, 2019 at 3:22 am

Greate post. Keep posting such kind of info on your blog.

Im really impressed by your site.

Hey there, You’ve performed an excellent job. I’ll definitely

digg it and in my view suggest to my friends. I’m confident they will be benefited from

this site.

quest bars cheap • Aug 24, 2019 at 1:15 am

I just like the valuable info you provide to your articles.

I will bookmark your weblog and take a look at again here frequently.

I am somewhat sure I’ll learn lots of new stuff right

right here! Best of luck for the following!

click here • Aug 23, 2019 at 8:58 am

This blog post is excellent, probably because of how well the subject was developed. I like some of the comments too though I could prefer we all stay on the subject in order add value to the subject!

quest bars cheap • Aug 23, 2019 at 4:19 am

I visited many blogs except the audio quality for audio songs existing at this web page is actually

excellent.

Badosa • Aug 22, 2019 at 7:17 am

Are grateful for this blog post, it’s tough to find good information and facts on the internet

walmartone login • Aug 21, 2019 at 9:53 pm

I am so grateful for your post.Much thanks again. Cool.

Boston Car Service • Aug 21, 2019 at 4:31 am

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post.Really thank you! Really Great.

KBI-017 • Aug 20, 2019 at 12:20 am

Thank you ever so for you article post.Really thank you! Will read on…

descargar facebook • Aug 19, 2019 at 7:08 pm

constantly i used to read smaller articles

or reviews which as well clear their motive, and that is

also happening with this piece of writing which I am reading at this time.

minecraft games • Aug 19, 2019 at 8:37 am

This article provides clear idea in favor of the new visitors of

blogging, that really how to do blogging and site-building.

voyance pas cher • Aug 18, 2019 at 10:28 pm

I really liked your blog article. Awesome.

minecraft games • Aug 18, 2019 at 12:38 pm

This is a good tip especially to those new to the blogosphere.

Simple but very accurate info… Many thanks for sharing this one.

A must read article!

descargar facebook • Aug 18, 2019 at 11:57 am

My partner and I stumbled over here different page and thought I

might as well check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you.

Look forward to looking at your web page yet again.

descargar facebook • Aug 18, 2019 at 6:53 am

Its such as you read my mind! You appear to grasp a lot about this, like you wrote

the ebook in it or something. I believe that you could do with

some percent to pressure the message home a bit, however other than that,

this is fantastic blog. An excellent read. I’ll definitely be back.

Trigona • Aug 17, 2019 at 9:31 pm

Thank you for your blog. Much obliged.

furniture hire • Aug 17, 2019 at 9:33 am

Awesome blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

ispoofer activation code • Aug 16, 2019 at 2:58 pm

Respect to website author , some wonderful entropy.

bouncy castle hire in hammersmith • Aug 16, 2019 at 12:55 pm

Hey, thanks for the blog article.Really thank you! Want more.

1 • Aug 15, 2019 at 2:03 pm

Fantastic blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

quarkxpress 2017 serial number • Aug 15, 2019 at 9:16 am

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, thanks .

feebhax not working • Aug 14, 2019 at 5:47 pm

Cheers, great stuff, Me enjoying.

plenty of fish dating site • Aug 14, 2019 at 3:30 pm

Hey very nice blog!

plenty of fish dating site • Aug 14, 2019 at 2:21 am

It’s in fact very difficult in this full of activity life to listen news on TV, so

I just use internet for that purpose, and get the most

up-to-date news.

plenty of fish dating site • Aug 14, 2019 at 2:11 am

It’s going to be ending of mine day, however before ending I am reading this impressive post to increase my know-how.

plenty of fish dating site • Aug 13, 2019 at 9:08 pm

An impressive share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a coworker who was doing a little homework on this.

And he actually bought me lunch because I discovered it for

him… lol. So allow me to reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!!

But yeah, thanx for spending some time to discuss this subject here on your website.

how to hack hoichoi app • Aug 13, 2019 at 9:03 pm

I’m impressed, I have to admit. Genuinely rarely should i encounter a weblog that’s both educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you may have hit the nail about the head. Your idea is outstanding; the problem is an element that insufficient persons are speaking intelligently about. I am delighted we came across this during my look for something with this.

plenty of fish dating site • Aug 13, 2019 at 12:02 pm

I really like what you guys are usually up too. This kind of clever

work and coverage! Keep up the awesome works guys I’ve

added you guys to our blogroll.

buy tramadol online • Aug 13, 2019 at 7:01 am

Im obliged for the article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

plenty of fish dating site • Aug 13, 2019 at 2:28 am

Incredible points. Great arguments. Keep up the amazing effort.

Polycrystalline silicon solar • Aug 10, 2019 at 10:10 am

wow, awesome blog article.Really thank you! Really Great.

answer the internet • Aug 10, 2019 at 8:09 am

I like this website its a master peace ! Glad I found this on google .

maca peruana tribulus terrestris • Aug 9, 2019 at 2:38 pm

Really appreciate you sharing this blog article. Great.

메이저토토 • Aug 8, 2019 at 6:38 am

Thanks-a-mundo for the blog.Really looking forward to read more.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCVqEwYdG-3757IGnLsXh0Gg • Aug 7, 2019 at 3:37 pm

Enjoyed every bit of your blog.Really thank you!

Ormekur kat hеndkшb • Aug 6, 2019 at 6:12 am

Hey, thanks for the post.Much thanks again. Really Great.

queens wedding venues • Aug 5, 2019 at 6:47 pm

Thanks again for the post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

roblox account generator • Aug 5, 2019 at 12:40 pm

I have interest in this, cheers.

homemade sex toy • Aug 5, 2019 at 6:10 am

Thanks for the post.Really thank you! Really Great.

Adam Eve coupon goodsearch • Aug 4, 2019 at 8:59 pm

Im grateful for the post. Much obliged.

best male sex toys • Aug 4, 2019 at 8:23 am

Awesome blog post. Cool.

the breakfast club • Aug 3, 2019 at 7:46 pm

Wow, great blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.

krunker io aimbot • Aug 3, 2019 at 8:24 am

I dugg some of you post as I thought they were very beneficial invaluable

Home Tutor Ranchi • Aug 2, 2019 at 7:06 pm

Im obliged for the post. Cool.

pof https://natalielise.tumblr.com • Aug 2, 2019 at 1:01 am

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up and let you know

a few of the pictures aren’t loading correctly.

I’m not sure why but I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different web browsers and both show

the same outcome. natalielise plenty of fish

plenty of fish • Aug 1, 2019 at 6:37 pm

Thank you for the good writeup. It in truth was once a enjoyment account it.

Glance complex to more brought agreeable from you! However,

how can we keep in touch?

plenty of fish • Aug 1, 2019 at 3:37 am

Hi there to every body, it’s my first go to see

of this web site; this webpage carries remarkable and truly

fine stuff for readers.

pof https://natalielise.tumblr.com • Jul 31, 2019 at 4:52 pm

Right away I am going away to do my breakfast, once having my breakfast coming yet again to read more news.

plenty of fish natalielise

plenty of fish • Jul 31, 2019 at 5:06 am

Nice post. I learn something new and challenging on blogs I stumbleupon everyday.

It’s always interesting to read through articles from

other authors and use something from other sites.

plenty of fish • Jul 31, 2019 at 5:06 am

First off I would like to say terrific blog!

I had a quick question that I’d like to ask if you do not mind.

I was curious to know how you center yourself and clear your mind prior to writing.

I’ve had difficulty clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out.

I do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the first 10 to 15 minutes are usually

lost simply just trying to figure out how to begin. Any suggestions or hints?

Thank you!

plenty of fish • Jul 30, 2019 at 9:37 pm

Awesome things here. I am very glad to see

your article. Thanks so much and I’m looking forward to contact you.

Will you kindly drop me a mail?

plenty of fish • Jul 30, 2019 at 5:15 pm

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m

trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good

results. If you know of any please share. Thanks!

xbox one mods free download • Jul 30, 2019 at 3:15 pm

Very interesting points you have remarked, appreciate it for putting up.

plenty of fish • Jul 30, 2019 at 4:58 am

Hello, this weekend is fastidious in favor of me, since this time i

am reading this impressive educational article here at my house.

pof • Jul 30, 2019 at 2:02 am

That is a good tip particularly to those fresh to the blogosphere.

Brief but very precise information… Thank you for sharing this one.

A must read article!

see this • Jul 29, 2019 at 11:30 pm

I truly appreciate this blog post. Awesome.

removals blackpool • Jul 29, 2019 at 10:46 pm

I am so grateful for your post.Thanks Again. Fantastic.

male stroker • Jul 28, 2019 at 9:44 pm

Really appreciate you sharing this article.Much thanks again. Much obliged.

Hundekurv • Jul 28, 2019 at 9:17 am

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic blog post. Fantastic.

bbw dildo • Jul 27, 2019 at 10:50 pm

Thanks for the article.

mastrubator • Jul 27, 2019 at 12:20 pm

Hey, thanks for the blog article. Awesome.

ezfrags • Jul 26, 2019 at 10:02 am

I like this site because so much useful stuff on here : D.

smore.com • Jul 26, 2019 at 12:51 am

Hey I know this is off topic but I was wondering if you knew of

any widgets I could add to my blog that automatically tweet my newest twitter updates.

I’ve been looking for a plug-in like this for quite some time and was hoping maybe you

would have some experience with something like this. Please let me know if you run into anything.

I truly enjoy reading your blog and I look forward to your new updates.

natalielise pof

ezfrags • Jul 25, 2019 at 8:57 am

Deference to op , some superb selective information .

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 25, 2019 at 5:44 am

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to

me. Nonetheless, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking

back often!

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 24, 2019 at 11:56 pm

This article will help the internet visitors for setting up new

weblog or even a weblog from start to end.

Change Bigpond Email Passwor • Jul 24, 2019 at 8:54 pm

Thanks a lot for the article post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

cant get licence key for farming simulator 19 • Jul 24, 2019 at 6:45 am

Ni hao, i really think i will be back to your site

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 23, 2019 at 6:31 pm

I really like what you guys are up too. This kind of clever work and coverage!

Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve added you guys to

blogroll.

ergonomic chairs • Jul 23, 2019 at 6:18 pm

I truly appreciate this post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

acid swapper • Jul 23, 2019 at 6:29 am

This helps. Cheers!

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 23, 2019 at 1:20 am

Howdy! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone 3gs!

Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all

your posts! Carry on the fantastic work!

Children martial arts in Natomas • Jul 22, 2019 at 5:59 am

Fantastic article.Really thank you! Awesome.

natalielise • Jul 22, 2019 at 4:29 am

I know this if off topic but I’m looking into starting my own weblog and was wondering

what all is required to get setup? I’m assuming having a blog like

yours would cost a pretty penny? I’m not very web savvy so I’m not 100% certain. Any recommendations

or advice would be greatly appreciated. Cheers pof natalielise

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 21, 2019 at 4:50 pm

Oh my goodness! Impressive article dude! Thank you, However I am experiencing problems

with your RSS. I don’t know the reason why I can’t join it.

Is there anybody having similar RSS problems? Anyone that knows

the answer can you kindly respond? Thanks!!

eebest8 seo • Jul 21, 2019 at 11:27 am

Thank you, I have just been looking for information about this subject for ages and yours is the best I have discovered so far. But, what about the conclusion? Are you sure about the source?

eebest8 seo

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 21, 2019 at 8:47 am

Fantastic goods from you, man. I have take note your stuff

prior to and you are simply too magnificent.

I really like what you have obtained here, really like what

you’re saying and the way in which you say it. You are

making it entertaining and you still take care of to keep it sensible.

I can’t wait to learn much more from you.

That is actually a tremendous site.

prodigy game files • Jul 21, 2019 at 7:58 am

I am not rattling great with English but I get hold this really easygoing to read .

https://www.uspslitebluelogin.net/ • Jul 20, 2019 at 2:20 pm

Really enjoyed this post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 20, 2019 at 4:06 am

Hi there, I discovered your site by the use of Google while looking for a similar subject, your

site came up, it seems to be great. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Hello there, simply become alert to your weblog thru Google, and located that it is truly informative.

I am gonna watch out for brussels. I’ll appreciate in case

you continue this in future. Numerous other people might be benefited out of your writing.

Cheers!

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 20, 2019 at 2:17 am

Magnificent items from you, man. I’ve be aware your stuff prior to and you’re just extremely

fantastic. I really like what you have obtained right here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which by which you assert it.

You’re making it entertaining and you continue to take care of

to keep it sensible. I can’t wait to read far more from you.

This is actually a wonderful site.

Hard Money Lending • Jul 19, 2019 at 3:15 pm

Appreciate you sharing, great article.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 19, 2019 at 11:11 am

Heya superb blog! Does running a blog such as this

require a large amount of work? I’ve absolutely no expertise in computer programming however I was hoping to start my own blog

in the near future. Anyway, if you have any suggestions or tips for new blog owners please share.

I understand this is off subject but I simply wanted to ask.

Thank you!

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 19, 2019 at 8:08 am

Hi there, i read your blog from time to time and i own a similar one

and i was just curious if you get a lot of spam remarks? If so how do you reduce it,

any plugin or anything you can suggest?

I get so much lately it’s driving me insane so any assistance is very much appreciated.

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 19, 2019 at 1:19 am

I constantly emailed this website post page to all my contacts, for

the reason that if like to read it afterward my links will

too.

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 18, 2019 at 6:09 am

Hi to all, the contents present at this website are actually remarkable for

people knowledge, well, keep up the nice work fellows.

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 18, 2019 at 4:26 am

At this time I am ready to do my breakfast, later than having my breakfast coming yet again to read further news.

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 17, 2019 at 8:59 pm

Currently it sounds like Movable Type is the preferred blogging platform out

there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that

what you are using on your blog?

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 16, 2019 at 10:58 pm

We’re a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with valuable info to work on. You

have done a formidable job and our entire community will be grateful to you.

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 16, 2019 at 10:08 pm

Howdy! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine

Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some

targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good success. If you know of any please

share. Thank you!

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 16, 2019 at 6:46 am

Usually I don’t learn article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very compelled me to take a look at and do so!

Your writing style has been surprised me. Thanks, quite

great post.

how to get help in windows 10 • Jul 16, 2019 at 6:17 am

I’ll immediately take hold of your rss feed as I

can’t in finding your email subscription hyperlink or newsletter service.

Do you have any? Kindly let me understand in order that I may subscribe.

Thanks.

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 15, 2019 at 4:44 am

Hello there! This blog post couldn’t be written much better!

Looking at this post reminds me of my previous roommate!

He continually kept preaching about this. I am going to send this article to him.

Pretty sure he’ll have a very good read.

Thanks for sharing!

plenty of fish dating site • Jul 15, 2019 at 1:25 am

I read this piece of writing completely on the topic of the resemblance

of latest and preceding technologies, it’s remarkable article.

quest bars • Jul 10, 2019 at 9:02 pm

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on quest bars. Regards

quest bars cheap • Jul 10, 2019 at 7:26 pm

Do you mind if I quote a few of your posts as long as I provide credit and sources

back to your weblog? My blog site is in the very same niche as yours

and my visitors would definitely benefit from a

lot of the information you present here.

Please let me know if this alright with you. Thanks a lot!

roblox fps unlocker • Jul 9, 2019 at 3:42 am

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, thanks .

quest bars cheap 2019 coupon • Jul 8, 2019 at 11:21 pm

I pay a quick visit every day a few web pages and sites to read articles or

reviews, except this blog provides quality based posts.

call of duty black ops 4 license key for pc free download • Jul 7, 2019 at 1:46 am

Morning, here from yahoo, i enjoyng this, I come back soon.

gx tool uc hack app download • Jul 6, 2019 at 3:39 am

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, thanks .

synapse x • Jul 5, 2019 at 11:25 pm

Respect to website author , some wonderful entropy.

erdas foundation 2015 • Jul 5, 2019 at 12:30 pm

yahoo brought me here. Cheers!

open dego • Jul 5, 2019 at 12:12 am

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, thanks .

subbot • Jul 4, 2019 at 11:57 am

I dugg some of you post as I thought they were very beneficial invaluable

vehicle simulator script • Jul 4, 2019 at 12:10 am

I was looking at some of your articles on this site and I believe this internet site is really instructive! Keep on posting .

cyberhackid • Jul 3, 2019 at 12:08 pm

Great writing to see, glad that duckduck took me here, Keep Up great Work

vn hax • Jul 3, 2019 at 12:13 am

Respect to website author , some wonderful entropy.

redline v3.0 • Jul 2, 2019 at 6:02 am

I consider something really special in this site.

escape from tarkov cheats and hacks • Jul 2, 2019 at 12:39 am

Some truly wonderful stuff on this web site , appreciate it for contribution.

cheat fortnite download no virus • Jul 1, 2019 at 12:38 pm

Thank You for this.

tinyurl.com • Jul 1, 2019 at 12:14 pm

you are actually a just right webmaster. The site loading speed is amazing.

It sort of feels that you’re doing any unique trick. In addition, The contents are

masterwork. you have done a fantastic task in this

matter!

http://tinyurl.com/y33fzurp • Jul 1, 2019 at 9:25 am

Whats up are using WordPress for your blog platform? I’m new to the blog world

but I’m trying to get started and create my own. Do you need any

html coding knowledge to make your own blog? Any help would be really appreciated!

nextgenerator net • Jul 1, 2019 at 1:55 am

I have interest in this, thanks.

cryptotab hack script free download 2019 • Jun 29, 2019 at 1:03 am

I am not rattling great with English but I get hold this really easygoing to read .

how to get help in windows 10 • Jun 28, 2019 at 11:10 pm

Hi there Dear, are you actually visiting this web page

on a regular basis, if so afterward you will absolutely get pleasant experience.

how to get help in windows 10 • Jun 28, 2019 at 8:52 pm

Woah! I’m really enjoying the template/theme of this blog.

It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s hard to get that “perfect balance” between superb usability and visual appearance.

I must say that you’ve done a awesome job with this.

Additionally, the blog loads super fast for me on Firefox.

Exceptional Blog!

advanced systemcare 11.5 serial key • Jun 28, 2019 at 6:16 am

I simply must tell you that you have an excellent and unique web that I must say enjoyed reading.

strucid aimbot script • Jun 28, 2019 at 12:34 am

I have interest in this, xexe.

synapse x serial key free • Jun 27, 2019 at 1:55 pm

I was looking at some of your articles on this site and I believe this internet site is really instructive! Keep on posting .

ispoofer • Jun 26, 2019 at 11:05 pm

bing bring me here. Cheers!

skisploit • Jun 25, 2019 at 11:43 pm

Ha, here from yahoo, this is what i was browsing for.

viacutan olie • Jun 25, 2019 at 6:36 pm

wow, awesome post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

qureka pro apk • Jun 25, 2019 at 1:04 pm

Good Day, happy that i saw on this in yahoo. Thanks!

Explain Like I’m Five • Jun 24, 2019 at 10:20 pm

Respect to website author , some wonderful entropy.

gx tool apk • Jun 24, 2019 at 8:25 am

I like this website its a master peace ! Glad I found this on google .

badoo superpowers free • Jun 23, 2019 at 10:21 am

Great read to check out, glad that google led me here, Keep Up great job

quest bars cheap • Jun 23, 2019 at 12:51 am

I’m gone to inform my little brother, that he should also go

to see this webpage on regular basis to obtain updated from latest reports.

plenty of fish dating site • Jun 22, 2019 at 12:12 am

Have you ever thought about writing an ebook or guest

authoring on other websites? I have a blog centered on the same subjects you

discuss and would love to have you share some stories/information.

I know my readers would enjoy your work. If you are even remotely

interested, feel free to shoot me an e-mail.

plenty of fish dating site • Jun 21, 2019 at 10:30 pm

It’s an remarkable piece of writing for all the

web users; they will obtain advantage from it I am

sure.

nonsense diamond 1.9 • Jun 21, 2019 at 12:56 am

I conceive this web site holds some real superb information for everyone : D.

vn hax pubg mobile • Jun 20, 2019 at 11:48 am

Thanks for this site. I definitely agree with what you are saying.

proxo key • Jun 19, 2019 at 3:04 am

I conceive you have mentioned some very interesting details , appreciate it for the post.

ปั้มไลค์ • Jun 18, 2019 at 5:53 am

Like!! I blog frequently and I really thank you for your content. The article has truly peaked my interest.

tinyurl.com • Jun 17, 2019 at 6:03 pm

excellent points altogether, you simply won a emblem new reader.

What would you recommend in regards to your publish that you made some days ago?

Any certain?

http://tinyurl.com/y2frreso • Jun 17, 2019 at 5:52 am

If you are going for finest contents like I do, only go to see this website all the time because it offers feature contents, thanks

aimbot download fortnite • Jun 16, 2019 at 8:22 pm

Good Day, happy that i found on this in google. Thanks!

quest bars • Jun 16, 2019 at 11:18 am

I have read so many articles about the blogger lovers but this paragraph is in fact a good post,

keep it up.

quest bars cheap • Jun 14, 2019 at 5:27 pm

Hey! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting

a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us useful information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

quest bars cheap • Jun 14, 2019 at 4:28 pm

Hey there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be okay.

I’m definitely enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.

quest bars cheap • Jun 14, 2019 at 4:59 am

I love it when individuals get together and share thoughts.

Great website, continue the good work!

playstation 4 best games ever made 2019 • Jun 12, 2019 at 10:15 am

Excellent items from you, man. I have remember your stuff prior to and you’re

just too fantastic. I really like what you’ve bought here, really like what you’re

stating and the best way during which you assert it. You make it entertaining

and you still take care of to stay it smart. I can’t

wait to read far more from you. That is really

a wonderful website.

ps4 best games ever made 2019 • Jun 12, 2019 at 6:21 am

Excellent post however I was wondering if you could write a

litte more on this subject? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit

more. Many thanks!

playstation 4 best games ever made 2019 • Jun 12, 2019 at 5:44 am

I pay a quick visit everyday a few blogs and information sites to read

articles, but this blog offers feature based articles.

playstation 4 best games ever made 2019 • Jun 12, 2019 at 4:26 am

Hi there, I do believe your site might be having internet browser compatibility

problems. Whenever I take a look at your website in Safari,

it looks fine but when opening in I.E., it has some overlapping issues.

I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Aside from that, great

blog!

gamefly free trial 2019 coupon • Jun 10, 2019 at 9:12 am

It’s really a nice and useful piece of information. I am happy that you simply shared this helpful information with us.

Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for

sharing.

http://tinyurl.com • Jun 10, 2019 at 1:58 am

Pretty section of content. I just stumbled upon your blog

and in accession capital to assert that I get actually enjoyed

account your blog posts. Any way I will be subscribing to your feeds and even I achievement you access

consistently fast.

ps4 games 2015-16 ign • Jun 7, 2019 at 4:03 pm

It’s actually a nice and helpful piece of info. I’m glad that you just shared this

useful information with us. Please keep us informed

like this. Thank you for sharing.

gamefly free trial • Jun 6, 2019 at 8:11 am

Attractive component of content. I just stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to say that

I get in fact enjoyed account your blog

posts. Anyway I will be subscribing in your augment or even I success you get admission to constantly quickly.

gamefly free trial • Jun 5, 2019 at 10:59 pm

Ahaa, its good conversation regarding this article here at this web site, I have read all

that, so now me also commenting here.

gamefly free trial • Jun 4, 2019 at 6:40 am

Hi! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a

group of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same

niche. Your blog provided us useful information to work on. You have done a marvellous

job!

gamefly free trial • Jun 4, 2019 at 4:18 am

Your mode of describing the whole thing in this piece

of writing is genuinely nice, every one be able to simply

know it, Thanks a lot.

gamefly free trial • Jun 3, 2019 at 10:40 pm

That is a very good tip especially to those new to the blogosphere.

Simple but very precise info… Appreciate

your sharing this one. A must read article!

gamefly free trial • Jun 3, 2019 at 4:10 am

You ought to take part in a contest for one of

the best sites on the web. I will recommend this site!

gamefly free trial • Jun 2, 2019 at 7:41 pm

Howdy would you mind letting me know which web host you’re using?

I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different internet browsers and I must say

this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you suggest a good web hosting provider at a fair price?

Thanks, I appreciate it!

gamefly free trial • Jun 2, 2019 at 8:27 am

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it.

Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! However, how

can we communicate?

gamefly free trial • Jun 1, 2019 at 1:11 pm

When someone writes an piece of writing he/she keeps the idea of

a user in his/her brain that how a user can understand

it. So that’s why this post is amazing. Thanks!

gamefly free trial • May 31, 2019 at 11:53 pm

I am regular visitor, how are you everybody? This post posted at this site is genuinely good.

gamefly free trial • May 31, 2019 at 9:38 pm

Thanks for a marvelous posting! I genuinely enjoyed reading

it, you can be a great author. I will be sure to bookmark your blog and will eventually come back very soon. I want to encourage you continue your great job, have

a nice afternoon!

gamefly free trial • May 30, 2019 at 12:11 pm

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point.

You obviously know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your blog when you could be giving

us something enlightening to read?

how to get help in windows 10 • May 30, 2019 at 9:00 am

If some one wishes expert view on the topic of blogging and site-building

then i advise him/her to pay a quick visit this web site, Keep up the fastidious job.

gamefly free trial • May 29, 2019 at 9:36 am

Hi, yeah this post is truly nice and I have learned lot of things from it on the topic of blogging.

thanks.

gamefly free trial • May 29, 2019 at 2:59 am

Hi there to all, how is the whole thing, I think every one is getting more from this web site, and your views are pleasant

for new people.

how to get help in windows 10 • May 28, 2019 at 9:00 am

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on how to get help in windows 10.

Regards