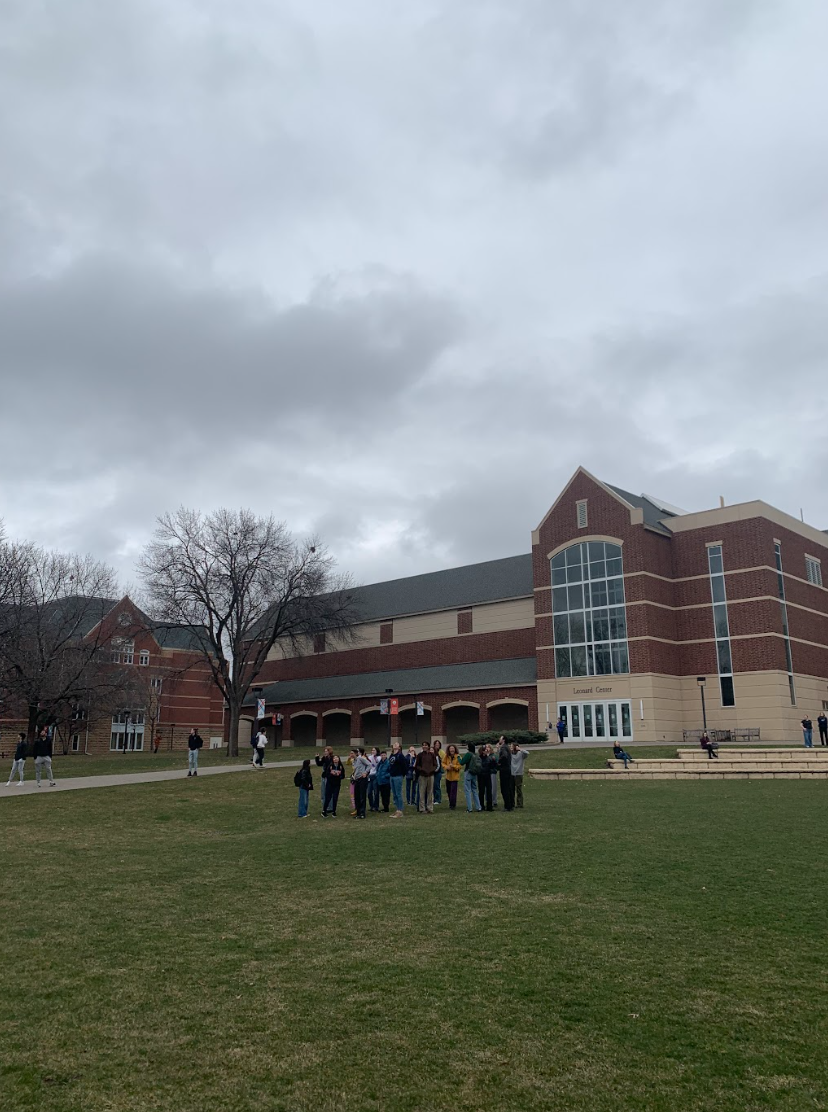

Macalester’s emphasis on social justice attracts students and attention to our campus. Despite this politically progressive orientation, many student activists have found their advocacy work is constrained. Student organizations have struggled to interact with the Twin Cities community and Macalester administration. Macalester’s rich tradition of student activism can inform current student activists about which tactics best overcome the “Macalester Bubble” and administrative obstacles.

Relating to the Twin Cities community is integral to successful organizing on Macalester’s campus. Uniquely situated in a metropolitan area, student activists now and throughout Macalester history can broaden their impact by taking their work off campus and partnering with community organizations.

In the 1960s and 70s, amidst the national surge in student activism in response to the Vietnam War, Macalester student organizations positioned their activism within the surrounding neighborhoods. The Macalester Committee for Peace in Vietnam distributed literature encouraging a community-wide boycott of Dow Chemical Company Products in 1967.

In 1970, students extended their activism into the summer when Twin Cities churches, schools and households allowed Macalester anti-war student organizations to use their buildings as meeting spaces. During that summer, eight student organizations representing an estimated half of Macalester’s student population wrote congressionally-sponsored proposals, distributed leaflets and held discussions with Minnesota women’s groups and high school students. Student organizations’ community connections allowed Macalester’s anti-war activism to assume a sober, determined and collective shape during a time when student activists were vilified as frenetic disruptors.

Chris Griffith ’92 detailed how the campus social justice organizations he was involved with interacted with the community. As a member of Proud Indigenous Peoples for Education (PIPE), Griffith saw Indigenous community members drawn to Macalester’s campus for PIPE powwows.

“Most of the people that came were Indigenous,” Griffith said. “In the Native community, drum groups are like rock bands, so people were coming from Manitoba and Winnipeg, from all over.”

Griffith was also a member of Maction, a student-run volunteering organization that would evolve into the Community Engagement Center.

“[Maction] volunteered at homeless shelters, women’s shelters and any community organization or nonprofit out there that needed help,” Griffith said. “We talked about [community engagement] … how do we get students off campus and how do we bring the community onto campus?”

A common critique of student activism is that on-campus change is too narrow of an objective. Dave Collins ’85, a librarian at Macalester, says on-campus advocacy is valuable.

“Pushing for changes on campus can lead to improvements for future students — even though those who organize may not see the change within their four year window,” Collins said.

Dr. Peter Rachleff, professor of history at Macalester from 1982-2012 and founder of East Side Freedom Library, agrees that campus and community organizing can be done in tandem.

“Why either/or?” Rachleff asked. “Couldn’t being active on both fronts strengthen impact on and off campus?”

A pro-Biafra relief group successfully married community and campus activism in 1968. National attention was on Minneapolis resident Ray Newgarden’s 19-day fast in response to the starvation crisis in the Nigeria-Biafra region. To catalyze this momentum, a 20-member Macalester group held a three-day fast in the Student Union, with 162 students joining for the last day. The group parlayed student support and media attention regarding their demonstration into a write-in, where students wrote to their congressmen urging for a ceasefire and U.S. aid to the Biafra region.

This demonstration bore real results: in a Dec. 1968 telegram written to Assistant Chaplain Alvin Currier, Senator Eugene McCarthy and Senator Walter Mondale, five representatives expressed their support for Macalester students’ and the surrounding Minnesota community action on behalf of those starving in Biafra. The congressional delegation then requested that President Johnson and President-elect Nixon appoint a representative for the sole purpose of expediting relief in the region.

Macalester’s administration is another body student organizations must grapple with. Tensions have risen on campus when Macalester student activism is directed inward.

Beginning in the late 1960s, Macalester financial connections to pro-apartheid corporations sparked a divestment movement. In 1970, the Macalester Proxies Committee began a movement to pressure the Macalester Board of Trustees into more transparency and student control in its shareholdings. Unsatisfied with the board’s proposal of a trustee relaying student demands at shareholder meetings, about 250 students entered and occupied 77 Macalester St. for three hours on April 16, 1970. During their occupation, students drafted a statement that demanded access to future trustee meetings, a student-controlled proxy rights model for the 1970 fiscal year and permanent shareholder voting procedures coherent with Macalester Proxies Committee’s proposal.

The Macalester Proxies Committee was confronted with administrative inelasticity. Most board members contacted during the occupation considered the occupation a nuisance. More moderate trustees worried the extreme members of the board would revoke their compromises or even seek reprisal. Despite student activists narrowing the scope of their demands to something feasible — transparency about where their tuition money was going — Macalester administration viewed the students as unreasonable and disruptive.

Griffith also found that administrative attitudes could act as both a barrier to or vehicle for the success of an organization. While Maction enjoyed administrative support and was eventually institutionalized, PIPE activists had to conduct a grassroots campaign for administration to charter their organization, which never happened during Griffith’s time at Macalester.

“[PIPE] went around to every door in administration … to explain who PIPE was and that we needed their support,” Griffith said. “For three years we were trying to get the school to take the [powwows] on as an institutionalized and sponsored event, which they never did. So we always felt a bit of resistance from [administration].”

Students’ limited time at Macalester complicates campus activism. Rachleff notes that students relate to communities less effectively as they are only considered temporary members. Administrations can ignore demands of students by simply waiting for them to graduate.

“Tactics that can affect real change require patience and organizing for sustained efforts — perhaps beyond the 4-year window of a student,” Collins said. “I think about the work of Fossil Free Mac, which went on for years.”

Fossil Free Mac, a student organization dedicated to Macalester divestment from fossil fuel companies, disbanded after seven years when the Macalester administration promised a moratorium on gas and oil investments in 2019. Their continuity over several classes of students inspired the digital toolkit “Fossil Free Mac Handbook: Lessons from a Divestment Campaign.”

Despite the obstacles organizations face, several mechanisms position Macalester students for more effective activism. Rachleff notes that student activism is akin to labor activism. Since both students and workers are already organized within an institution, it is easier for activists to establish important relationships. Macalester’s small size and residential nature allows for better connections between student activists.

“There’s no ‘there,’ at large commuter colleges,” Rachleff said. “Macalester is a much more fruitful space [for student activism.]” Social justice organizations at Macalester also drew Griffith closer to the community within Macalester’s campus.

“All of my [student activism] experiences were incredible bonding experiences,” Griffith said. “It was social but also had purpose. I think that is a potent combination.”