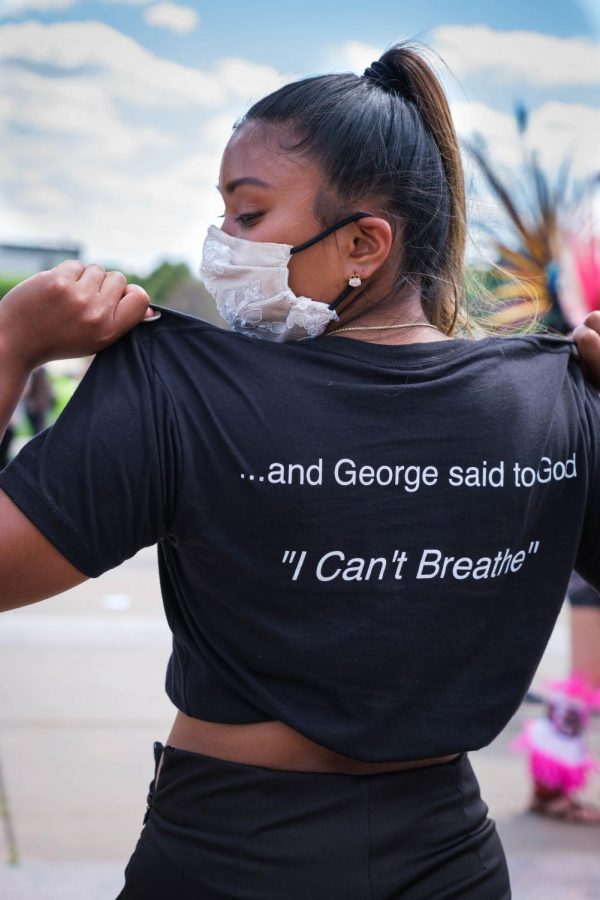

Families of police brutality victims march on the capitol

July 14, 2020

On Sunday July 12, over 100 people from around the country gathered in the Twin Cities for the National Mothers March to tell the stories of their sons, fathers, sisters and mothers killed or brutalized by police.

Speaking at the beginning of the march and again on the capitol lawn, family members reiterated their central demand: that officials reopen every one of their cases.

Some have seen officers fired or sent to prison for a few years; some have received monetary settlements; some haven’t seen anyone held accountable. All of them said it wasn’t enough — their loved ones are never coming home.

Dionne Smith-Downs’ 16-year-old son was killed by Stockton police officers in 2010. She addressed the crowd from the steps of the capitol, surrounded by the rest of the families.

“I drove from Stockton, California all the way here when I heard George Floyd say, ‘mama,’” she said. “He was calling all the mothers. The universe had opened up.”

At a private event on Saturday, July 11, family members gathered for a day of workshops and storytelling. Ashley Quinones, who has been organizing for justice since her husband Brian was killed by police in Bloomington in December 2019, opened the event.

Quinones hoped this would be a chance to give families a platform to speak and be heard.

“This is an event that is geared by families — ran by families and for the families — and that’s exactly what needs to happen going forward,” Quinones said.

Several of the family members who stepped forward to speak noted that those chances are few and far between. Many of their loved ones’ names faded from the headlines several years ago — or never made it there in the first place.

Nicole Pettiford traveled from Baltimore, Md. to represent her father-in-law, Anthony Anderson, who was killed by police in 2012. Two weeks later, she lost her newborn daughter. She has been telling their stories ever since.

“What they fail to realize, and what you all here need to understand: they can’t kill you until they kill your name,” Pettiford said. “As long as I have breath in my body… we will never die.”

Some families are newcomers to this community of healing and activism. Breonna Taylor’s cousin, Preonia Flakes, has been mourning — and organizing — for four months. She traveled to the Twin Cities to tell her cousin’s story, and to remind the crowd that even one of the most well-publicized cases still hasn’t seen a resolution.

“No justice has been brought to any of us, and we’re fighting daily, sun up to sundown, to bring the officers, charge them and lock them up,” Flakes said.

She took a break midway through her speech, struggling to keep talking. The other family members were quick to offer support, calling out, “we got your back.” After a moment, she continued.

“As my favorite cousin, my partner, my sister, I just want to keep her name alive,” Flakes said. “I want you all to know her story, and I want you all to keep saying her name.”

Some families here have spent years fighting for justice for their loved ones, and for an end to police racism and violence. Cephus Johnson, better known publicly as Uncle Bobby X, has been doing this work since his nephew Oscar Grant was killed by police in Oakland, Ca. in 2009.

Grant’s murder was one of the first instances of police violence against Black Americans to be filmed and widely publicized, and Uncle Bobby X has been in the limelight since, crafting a network of families impacted by police violence. That community has grown to include over 300 families connected through Families United 4 Justice, which he helped found in 2014.

If lawmakers and the public had heard the urgency of Grant’s story, Uncle Bobby X said, countless cases of police violence could have been avoided. The officer who killed Grant was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and served 11 months in prison. Uncle Bobby X has been working for 11 years.

“Because we failed in that respect, what we saw happening was a green light given to police officers to articulate why they killed him and get away with murder,” he said. “It’s only going to get worse if we fail to do it today.”

Although the repeated line in the marchers’ speeches and stories was a demand for law enforcement to reopen closed cases, the speakers pressed for a deeper goal, as well: an overhaul of the justice system and accountability in law enforcement.

With the surge of the Black Lives Matter movement over the last couple of months, Uncle Bobby X hopes this might be a turning point in a long fight.

“I see this as a window of opportunity to bring in real legislative change,” he said. “It’s our hope that as families show up… they be given the chance to sit at the table to bring about the change, and what we see happening today is just that.”

Kori Suzuki contributed to the reporting of this story.