The men Macalester immortalized

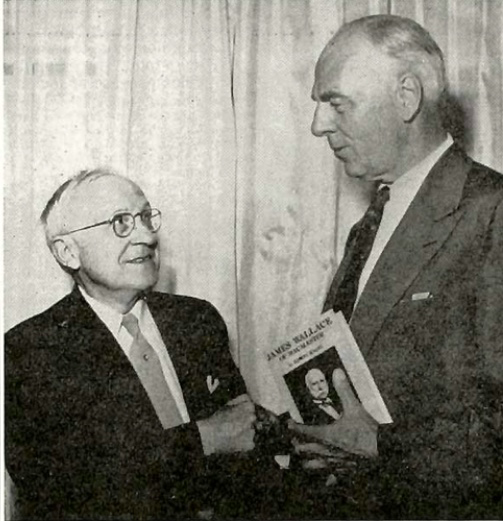

Edwin Kagin and DeWitt Wallace. Photo from The Mac Weekly archive.

October 31, 2019

Emblazoned over the entryway to a building, carved into a wooden sign outside a dorm, etched into a stone plaza. Nearly every hall, atrium and meeting room at Macalester is marked with the name of a towering figure from the college’s history.

But while these names are part of the everyday vocabulary of the people who have lived, worked and studied at Macalester, their origins often remain somewhat obscure.

DeWitt Wallace

Every night, the last building on campus to turn off its lights is the DeWitt Wallace Library.

The son of former Macalester president and professor James Wallace, DeWitt Wallace was born in St. Paul in 1889.

Wallace attended Macalester from 1907 until 1909, before transferring to the University of California, Berkeley for another two years and then joining the U.S. Army during World War I.

After suffering a combat injury in France in 1918, Wallace spent most of his time in a hospital bed reading American magazines, contemplating one day putting together a publication that condensed a series of articles from various magazines into a single publication.

After returning to the United States, Wallace met and eventually married Lila Acheson in 1921 and together they scraped together enough money to print their first Reader’s Digest in 1922. The first several issues made little profit, but by 1929, the magazine had 290,000 subscribers and was sold on newstands across the country.

In her book, “Condensing the Cold War: Reader’s Digest and American Identity,” historian Joanne Sharp writes that early on, Reader’s Digest established itself as fiercely anti-communist and supportive of an anti-Semitic America-first foreign policy.

During the mid-1930s, the publication routinely compared Joseph Stalin to Adolf Hitler — with one indicative article arguing that “violence is the very nature of the communist dictatorship.”

The Digest became a massive financial success in the early 1930s, and it was around that time that Wallace began to donate to Macalester.

Wallace’s first major donation came during the college’s capital campaign of 1938, when he and his wife made a donation of $500,000 — roughly equivalent to $9 million today.

Wallace wanted Macalester to become a nationally-recognized institution and leader among Midwest colleges. He encouraged then-Macalester President Charles Turck to make the college’s admissions process more selective.

Another area of focus for Wallace was faculty salaries. He established five endowed professorships, and created a fund for faculty to obtain their doctorate degrees.

In addition, Wallace launched the High Winds Fund in 1956 — enabling the college to purchase rundown homes in the neighborhood, repair them and sell them to faculty members.

Meanwhile, Reader’s Digest continued to amplify conservative, anti-communist views well into the 1940s, publishing excerpts from works of Whittaker Chambers and Friedrich Hayek.

In 1941, Wallace published excerpts of Anne Lindbergh’s 1940 book “The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith,” in which Lindbergh praises Hitler and argues that Nazism could be the blueprint for the future of humanity.

In his 1998 biography of Charles and Anne Lindbergh, historian A. Scott Berg characterized this book as one of the most despised books of its day — “surpassed only… by ‘Mein Kampf.’”

Nevertheless, Wallace called it the “article of the year” after its publication in the Digest.

Wallace’s consistent beneficence enabled the college to boost its academic clout during the 1950s and 60s. At the same time, the college was looking to improve the diversity of the student body.

In the fall of 1967, there were only 39 black students on the Macalester campus — and many of those students asserted that the college was not making any concerted effort to bring in more students of color.

When Macalester President Arthur Flemming started at the college in the summer of 1967, he made advancing racial equality his priority, and, with Flemming’s support, several faculty members began writing a proposal for a program aimed at bringing low-income black Americans to the college.

By December 1967, the group had a proposal for the Expanded Educational Opportunities Program (EEO) to provide full scholarships to 75 students each year — and, in January, the board of trustees earmarked $900,000 over a three-year period to fund it.

The college, however, was struggling financially under Flemming’s presidency. Wallace himself frequently made up budget shortfalls at the end of a fiscal year.

But by 1967, Wallace had grown tired of balancing the budget. He wanted to fund innovative programs, not operating expenses, and felt some individuals at the college were taking his support for granted.

In January 1971, Wallace’s educational advisor Paul Davis made the announcement that Wallace would terminate his giving to the college. The news landed on the front pages of both the Minneapolis Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

Reporters quoted Davis as saying that Macalester had become “too affluent” and even extravagant in its spending. The Minneapolis Tribune mentioned the EEO program, which cost the college $827,000 the year prior.

Davis said that while “programs for minority students are essential to the United States,” he was not sure whether Macalester could take one on.

In the midst of this financial crisis, Flemming resigned in spring 1971 and was replaced by James Robinson the following fall. Almost immediately, the EEO was swiftly and significantly cut — and students took note. In September 1974, a group of students staged a 12-day protest of cuts to the EEO that included a takeover of the administrative offices located at 77 Macalester Street.

Eventually, Robinson and student protestors agreed on a compromise and the protest ended. Later that fall, however, the board of trustees revoked the agreed-upon compromise, claiming that Robinson didn’t have the authority to engage in negotiation.

The next year, only 22 EEO students entered Macalester with partial scholarships. The program officially dissolved in 1984.

Last spring, as part of the Naming Hate lecture series, Zain Mahmood ’20, Jennings Mergenthal ’21 and Teresa Padrón ’21 gave a talk on the history of Macalester in which they spoke extensively about the legacy of Wallace’s contributions to Macalester.

The students tied the withdrawal of Wallace’s support directly to the downfall of the EEO.

“Given how [the] EEO was perceived and [given] the Reader’s Digest’s political leanings, it seemed pretty clear that DeWitt Wallace probably didn’t see EEO as a program that was boosting the college’s reputation — even though I’m pretty sure it was,” Mahmood said.

“It was a pretty popular program amongst people who were looking at diversity,” they said. “It was considered a groundbreaking program.”

DeWitt Wallace, age 91, died in his home in Pleasantville, N.Y. in 1980 — but not before he once again single-handedly changed Macalester’s financial destiny.

During the winter of 1975, four years after he ceased giving to the college, Wallace agreed to release seven million dollars in restricted endowment funds to be applied to the college’s growing debt.

Then, one month before his death, Wallace made his final gift: an additional 10 million shares of Reader’s Digest stock.

Reader’s Digest went public in 1990, and Macalester’s endowment almost quintupled over the course of a year — growing from $60 million in 1989 to $325 million in 1990, and cementing Wallace’s legacy at the school.

That legacy was also built in brick and mortar.

In September 1988, eight years after his death, the newly-built DeWitt Wallace Library was named in honor of the man who donated so much of his personal wealth to Macalester. The cost of construction was $15 million, funded by a combination of alumni donations and Wallace funds.

Frederick Weyerhaeuser

The previous library had also been funded by the Wallaces, though it bore a different name.

After DeWitt and Lila Wallace made their first major donation, the college built a series of buildings, including a new library. The building was constructed in 1942 and named after esteemed trustee Frederick Weyerhaeuser. It is now Weyerhaeuser Hall.

Weyerhaeuser was born in 1834 to a poor family in Germany. In 1853, he came to the United States to find work. After arriving in Pennsylvania, he settled down in Illinois — working in a small lumberyard where he met his soon to be brother-in-law, Frederick Denkmann.

In 1860, he and Denkmann purchased a bankrupt lumber mill in Rock Island, Illinois. After turning the once-failed mill into a huge success, the pair purchased several more mills and eventually started the Mississippi River Logging Company in 1872.

Weyerhaeuser eventually became president of the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, the Weyerhaeuser Syndicate and several other lumber companies — completing his rise from relative poverty to riches.

Weyerhaeuser moved to St. Paul in 1891 to be closer to the forests of northern Minnesota, which represented a massive profit opportunity for his companies.

He quickly spread his empire, buying the C.N. Nelson Lumber Company at Cloquet, Minn. and, with it, 600 million feet of standing lumber.

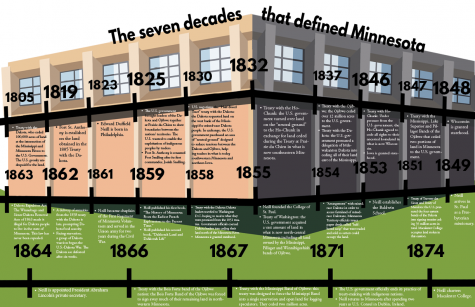

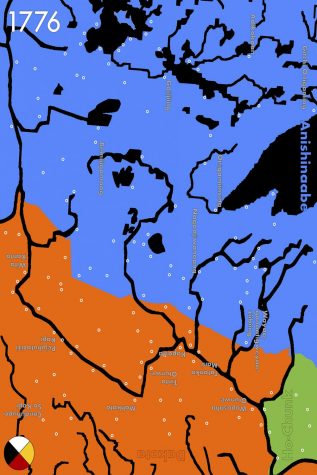

Part of the city of Cloquet lies within the Fond du Lac Indian Reservation. The U.S. government created the Fond du Lac reservation in 1854 after the Lake Superior and Mississippi Bands of the Ojibwe people ceded a large portion of their land to the federal government in exchange for annuities, cash, goods and payment of debts to traders.

In 1899, St. Paul-based railway tycoon James J. Hill sold 900,000 acres of land in the Pacific Northwest to Weyerhaeuser — one of the largest private American land sales at the time. After the sale, Weyerhaeuser owned more acres of standing timber than any other American.

Meanwhile, in the Cities, Weyerhaeuser found himself occupied by matters of faith.

In the early 20th century, Weyerhaeuser began to donate to a local Presbyterian school in his neighborhood — Macalester College. After being named a trustee, in 1911 he donated $50,000 — roughly $1.3 million in today’s money.

Weyerhaeuser and his foundation played a role in cementing the college’s religious values in its academic identity. Even after Weyerhaeuser’s death in 1914, the Frederick Weyerhaeuser Foundation endowed Macalester’s new Department of Religious Education in 1915.

However, by the mid- to late-1920s, the college began to question its evangelicalism and its mission of advancing Christianity. Students, faculty and staff were divided on the direction that the college’s religious affiliation could take: some were loyal to the college’s original conservative Presbyterian roots, while others wanted space for more progressive practices of worship and thought.

The Weyerhaeuser family lobbied the college to maintain its Presbyterian identity.

Weyerhaeuser’s two sons, Frederick and Rudolph, both made donations of $100,000 to Macalester’s fundraising campaign at the end of 1937. The endowment guaranteed that the college would maintain its relationship with the Presbyterian church. Funds gifted by the Weyerhaeusers also endowed Macalester’s chaplaincy.

In 1962, after the college decided that it would build a chapel on its campus, Weyerhaeuser’s daughter, Margaret, offered to fund the construction of the building as a memorial to her father.

The proposed chapel quickly became a point of contention. Some students, faculty and staff resisted its construction, mainly because the Weyerhaeusers supported compulsory attendance at weekly chapel services on Wednesday mornings.

The issue was not resolved until 1966, when the board decided to make chapel attendance optional.

Once made voluntary, chapel attendance dropped to 10 percent — a statistic consistent with other religious colleges who had eliminated the compulsory attendance requirement.

Nevertheless, the chapel named in honor of Fredrick Weyerhaeuser was built and dedicated in 1969.

Franklin W. Olin

On the other side of campus, another building is named for yet another powerful businessman and Macalester benefactor: the Olin-Rice Science Hall, named, in part, after Franklin W. Olin.

Olin had very little formal schooling after the age of 13, but knew from a young age he wanted to be an engineer.

According to a profile of Olin from the Olin College of Engineering, he was a largely self-taught inventor who, in his youth, worked as a farm machinery repairman before he passed the Cornell University entrance exam.

In the 1880s and 90s, however, his innovations turned more profitable when he began building gunpowder mills in rural Illinois.

By the 20th century, his companies had grown. One of them, Western Cartridge, supplied ammunition to the U.S. Army during both World Wars. According to the same Olin College profile, the company eventually became the “greatest small arms ammunition maker in history, producing more than 14 billion rounds.”

But while it raked in money, the corporation was engaged in discriminatory hiring practices throughout the early 20th century. In 1944, prominent civil rights activist and chief lobbyist for the NAACP Clarence Mitchell Jr. wrote that the Olin Corporation refused to hire black employees because they “preferred not to do so.”

Olin himself died in 1951, but the present-day Olin Corporation, a Fortune 500 company, lives on as a multi-billion dollar chemical producer.

The company also remains prominent in the weapons industry. Its subsidiary, Olin Winchester, has active contracts with the military. In September 2019, for instance, the U.S. Army chose the company to manage the Lake City Army Ammunition Camp in Independence, Mo.

Meanwhile, the F.W. Olin Foundation, which was active from 1938 until 2005, funded the creation of nearly 60 engineering facilities across the country. In 1997, it was used to establish the prestigious Olin College of Engineering in Needham, Mass.

While Olin was not directly affiliated with Macalester College, his foundation gifted $1.6 million for the construction of what was once the Olin Science Hall in November 1962.

At the time, the contribution was celebrated. A Mac Weekly article from the time pictures DeWitt Wallace cheering the Olin Foundation with “nine rahs.”

The original building was merged into the Olin-Rice Science Center in a 1997 renovation.

Of the college’s seven academic buildings, four are named after white men and one is named after a white woman. The ratio is worse for the eight dorms, six of which are named for white men and one for a white woman.

The remaining two academic buildings and one dorm are not named after people.

For Anael Kuperwajs Cohen ’21 and Juliet Kelson ’20, who organized the college-wide event Naming Hate last year, the names of Macalester’s buildings are a statement of the college’s priorities.

“When you see yourself in a place, it’s easier to connect to the place and it’s easier for you to feel like you belong,” Kuperwajs Cohen said. “We don’t look up to the figures that are important in Macalester [history] as anyone but white men, and that’s a big deal.”

Both agreed that Macalester must drastically change its priorities to better meet the needs of individuals from marginalized and historically underrepresented communities. The first step is making a change in whose contributions are honored and how.

“[It] is a way to keep people out of spaces… by making them uncomfortable and by saying, ‘Our priority is to honor this bad person,’” Kuperwajs Cohen said. “That’s kind of saying, if we’re honoring that person, we’re agreeing with them. It’s essentially saying ‘We don’t want you here.’”

Kelson agreed.

“You’re telling people every day [that] the money and the founding of this school are more important than you and your experience.”

This article is part of the Mac Weekly’s special reporting project, Colonial Macalester. Read the entire issue here.

Allen Charles Glorvigen '63 • Nov 19, 2019 at 2:30 pm

Are you suggesting that there were others who did more (or as much) for the college and therefore, whose names should on our college buildings instead?

Their names and their stories should be known to all.

Del Ehresman • Nov 4, 2019 at 1:38 am

Regarding the land transaction between Weyerhaeuser and Hill, note that 1899 was not the 20th century.

The Mac Weekly • Nov 4, 2019 at 9:25 am

Thank you for bringing that to our attention, the error has since been fixed.

Scott Teegee • Nov 3, 2019 at 11:51 am

This “In 1899, St. Paul-based railway tycoon James J. Hill sold 900 acres of land in the Pacific Northwest to Weyerhaeuser — one of the largest private American land sales in the 20th century.” should say 900,000 acres. Big difference.

The Mac Weekly • Nov 3, 2019 at 12:34 pm

Thank you for bringing that error to our attention. It has since been corrected in the article.