Pride, prejudice, and consumerism: The role of period piece romances in the 21st century

February 23, 2023

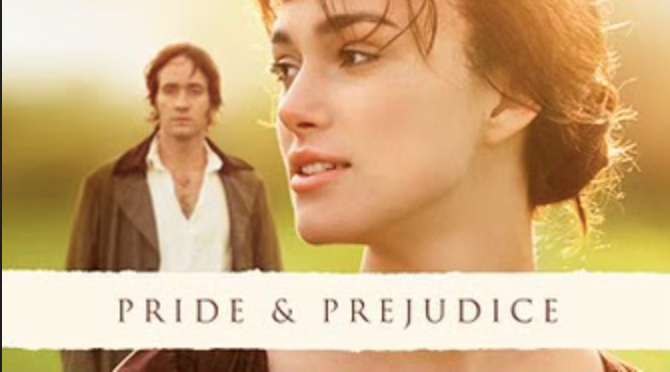

When the television show Bridgerton was released in 2020, it broke conventions of regency period dramas before it, most notably the movie Pride and Prejudice (2005), had cemented as a genre. Period pieces are characteristically known for slow burn romance and the meticulous process of courtship that takes its sweet time. On the other hand, Bridgerton took the aesthetic of the regency period without the cultural reality of the time. The show is a great example of the way Gen Z engages with period dramas, indicative of today’s dating and courting culture. In such a consumer-driven society, the speed at which we go through trends is beginning to translate into the way we build relationships of all types. The intensity of trend culture has created a revolving door of identities and aesthetics that, much like modern-day romance films, is fast-paced and surface-level.

Envision this: you have just written a letter to your lover, whom you have not seen since last season, awaiting a response that will take another month or so to arrive. Our access to an exhausting amount of choices disables our ability to synthesize the world around us. Dating applications, like Tinder, expose us to a variety of people, faces and stories that begin to imitate sites like AliExpress and Amazon, where the line between commodification and reality begins to thin. Period piece romance films have become the antithesis to today’s consumer culture of instant gratification.

Period pieces, like Pride and Prejudice, draw out romantic interactions over months, even years, creating a longing and tension between the characters and the audience. Seeing each other a limited amount of times allows for character development, where each protagonist takes their time understanding each other and their romantic circumstances. The pressures to give in to the coupling are often from their family instead of the modern culture of romantic instant gratification.

Pride and Prejudice, an adaptation of the Jane Austen novel by the same name, has become one of the most prolific period piece dramas, earning itself a cult following. The film follows Elizabeth Bennet, one of five daughters of an upper-middle class family, and her tumultuous relationship with Fitzwilliam Darcy, a landowning aristocrat. When they first meet at a ball, Darcy insults Elizabeth and quickly gains a reputation of being pompous and rude. However, as the story progresses, Darcy and Elizabeth find themselves in situations in which they are forced to interact with one another, as Darcy’s good friend, Bingley, has fallen in love with Elizabeth’s sister, Jane. Despite his actions, Darcy has been wooed by Elizabeth’s charm and asks her to marry him. She declines his offer, stating, “Yyou were the last man in the world I could ever be prevailed upon to marry.” However, Darcy manages to redeem himself to Elizabeth by saving her younger sister from disgracing the Bennet family name. When they meet again, Darcy asks Elizabeth to marry him once more and she agrees. Despite the month-long gaps in between their meetings, they still fall for each other, and in the end, it is his actions and devotion to her that encourage Elizabeth to marry him.

Elizabeth and Darcy are forced to be patient in their relationship, which allows them to foster other relationships that are not romantic, like familial and platonic. Modern-day love stories falsely narrativize expectations of love, implying one’s romantic partner should be more important than any other, hindering one’s ability to foster other platonic and community sourced love. The subplot of Darcy saving the Bennet family’s reputation is a perfect example of this. Elizabeth’s younger sister, Lydia, is deceived by Wickham, a man who is at odds with Darcy over money, to run away with him under the pretense of marriage. However, Wickham has no intention of marrying Lydia, and this elopement puts the Bennet family at risk of being disgraced. Once the family learns of this news, they are all beside themselves, and the importance placed on saving Lydia from Wickham by Elizabeth makes it clear how important family is to her and her relatives. It is this reason that Darcy is able to redeem himself in Elizabeth’s eyes, as he secretly pays Wickham to marry Lydia, and handles all of his debts that would have affected the Bennet family otherwise.

Romantic patience in period pieces is so common because it is a product of their era. These stories often span months and years because they had to. There were no cars, let alone cell phones or dating apps. The 1800s equivalent of the “talking stage” was the lengthy process of courting in order to get to know someone. However, a slow burn romance is not unique to the movies set in the regency period, nor is an enemy-to-lovers romance. In fact, there are many that achieve the same effect in modern day settings, like 10 Things I Hate About You (1999) or When Harry Met Sally (1989).

Romance is a billion-dollar industry that has profited from consumer culture two-fold: our obsession with romantic love and our need for instant, feel-good romance. As we experience consumer burn-out, unable to follow a trend because there are so many, shopping for a new Skims top and swiping at the end of the night become a parallel activity. Period dramas, in a time where consumer culture has not sunk its teeth into every social activity, becomes a method of escapism. As we watch period dramas, we see people reading, resting, playing instruments and doing activities other than working a 9-5 with no paid leave. Pride and Prejudice encapsulates activities and relationships that seem to be drowned out by the insistence of consumerism. Elizabeth and Darcy did not match on Tinder, they initially did not even match in real life, but the element of time and patience was a virtue that granted a depth to their relationship unseen in modern-day romance films.