You’re not (yet) graduating into a recession

February 9, 2023

In the past couple months, prominent tech companies have laid off sizable portions of their workforces. Google, for example, recently let go of 12,000 employees, contributing to an estimated 60,000 tech workers laid off in the last month (roughly 30 times the size of the Macalester student body). Perhaps you have seen headlines about similar layoffs in other industries, too: this month, Vox Media laid off seven percent of their workforce and the Washington Post let 20 reporters go while deciding to leave another 50 positions open. And the investment bank Goldman Sachs cut over 3,000 employees in January.

As an undergraduate observer, such news might seem like cause for concern. Facing the prospect of a recession is no fun for a student. Graduating into a recession means struggling to find a good job, and if you can find a job, accepting one for worse pay. If a recession continues for a while — as it did in 2008 — then you can expect to have dismal wage growth thereafter. The market for internships would look worse in a recession—in a 2021 interview with The New Republic, sociologist Carrie Sandra said that the Great Recession’s weak labor market saw employers increase the education and skill requirements for interns (a trend that did not reverse afterwards). Further economic research finds that those who graduate into recessions can face long-term harms to their career prospects and health.

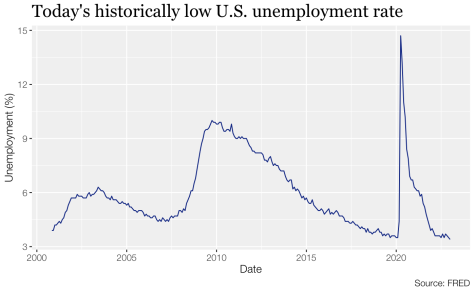

But in spite of layoffs in a couple of prominent industries, there is good news: we are not there yet. While the risks of a recession in the coming months have not disappeared, we are currently experiencing something like the opposite of a recession: on Feb. 3, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 517,000 jobs were added to the economy, and that the national unemployment rate fell to 3.4%—the lowest U.S. unemployment rate since The Beatles broke up.

The Federal (the Fed) Reserve has been fighting to lower inflation, relying on their primary tool of raising interest rates. Through a somewhat abstruse process, this reduces the ability of businesses to borrow money, meaning that they must reduce their investment. Inevitably, they also shrink their labor forces, leaving people jobless.

While taming abnormally high inflation is a valid goal, these efforts also risk creating a recession: the higher interest rates go, the more businesses pull back on their investment and the more people lose their jobs. Additionally, as economist Alex Williams has written, when unemployment goes up a little, it tends to go up a lot. Once people are getting laid off en masse, others may reduce their spending for fear of losing their jobs too, forcing businesses to further shrink their workforces. Such is the doom loop of a recession.

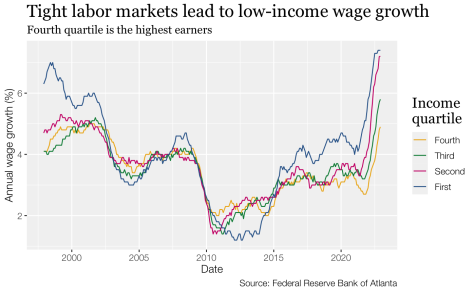

For workers, recessions bring the problem of a “loose,” or weak, labor market. This describes the general matchup between workers and employees: when the labor market is loose, there are many workers looking for employment but few firms hiring. As a result, workers have minimal bargaining power—prospective employees can either take the job they are offered, or face unemployment. Once employed, workers are unable to switch jobs if their current one sucks, and they cannot bargain for better wages. Unsurprisingly, it is the least-educated and lowest-earning workers who suffer the most in such an environment.

But in a “tight” labor market, these dismal trends reverse. That is why 2021 saw the highest-ever rate of people quitting their jobs—not because people stopped working altogether but because they were empowered to leave bad jobs for better ones.

Today, the labor market continues to be beneficial to workers. As the journalist Emily Stewart recently wrote, layoffs in a few prominent areas do not spell doom for the rest of the job market. There has been no noticeable uptick in claims for unemployment insurance, wh

ich is one common indicator of nation-wide job losses. The employment-to-population ratio for 25-54 year olds, which measures how many “prime-age” workers have jobs, is nearly at its pre-pandemic heights. And the lowest-earning workers continue to see the fastest wage growth—even outpacing inflation.

So we are doing more than just avoiding a recession—we are experiencing a really favorable labor market for workers. And for the reasons listed above, that is great news for college students as they look for summer jobs or begin their post-graduation careers.

Of course, there are still problems. Inflation has not returned to the Fed’s target of two percent, and they will continue to raise interest rates to pursue this goal, even if that entails higher unemployment. Sector-specific disruptions are still omnipresent—eggs, for example, just went through a massive spike in prices. A tight labor market, while beneficial, cannot fix all or even most of our economic problems. Yet we should keep in mind that recent macroeconomic news is mostly good news—for students and for workers everywhere else.

Alex • Feb 17, 2023 at 7:13 pm

Zak, you are the best!