Corrie Grosse talks environmental activism for EnviroThursday

November 17, 2022

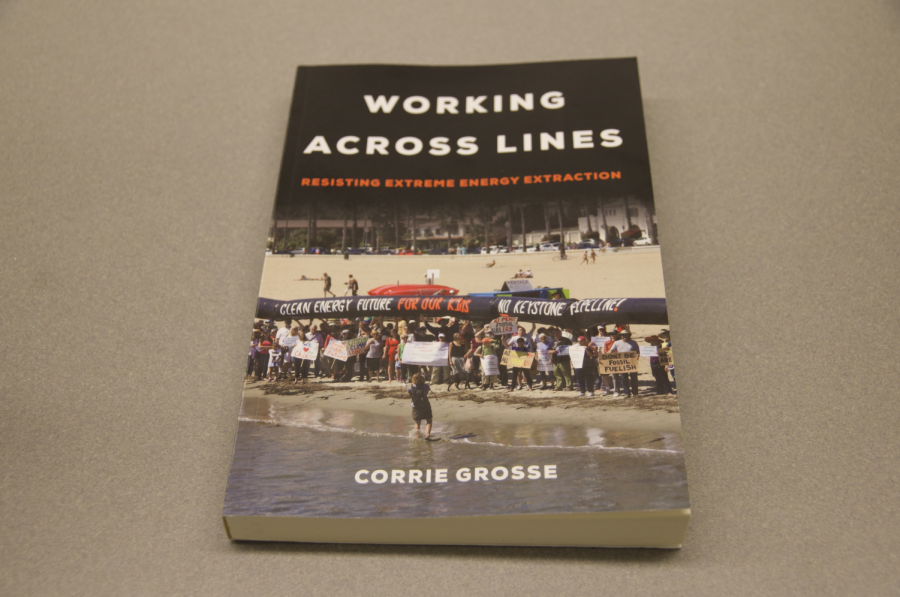

On Thursday, Nov. 10, members of the Macalester community gathered to listen to Corrie Grosse, an assistant professor of environmental studies at the College of Saint Benedict & Saint John’s University, speak about her experiences with two environmental movements, anti-oil and fracking in Idaho and California respectively. She also shared how those movements have changed her perspective on activism and how it should be conducted.

Grosse began the discussion by talking about her experience in Idaho where oil companies used rural highways to ship megaloads to the tar sands in Canada. Megaloads are 650,000-pound pieces of equipment that are used to process tar sands into usable oil. Idaho has the furthest inland port connected to the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River, and thus was the starting point for these megaloads.

These oil companies used rural highways, specifically Highway 12, for transport since normal highways have overpasses that don’t fit the megaloads. However, because Highway 12 is only two lanes, the megaloads took up the entire road, rendering the road useless during their transport.

People protested the transportation of megaloads for a variety of reasons, ranging from concern for the local environment and nature along the highway to anger over their destination, the tar sands.

Since the transport of megaloads prevented people from using the road, they stopped traffic, interrupted business along the road and disrupted the communities they went through. Highway 12 is an important thoroughfare for Idaho, connecting metropolitan areas across the state. This made the megaload interruption extremely difficult for Idahoans.

“[Highway 12] is the only road for hundreds of miles, so [for] people who live along the highway it’s the only way to get to the hospital,” Grosse said. “There were concerns about that.”

Grosse discussed the diversity of activism in response, including protests around the permits to transport megaloads, arguments with ExxonMobil presenters over their use of the tar sands and even people timing how long megaloads stopped traffic to prove they were breaking the law. She also emphasized that the collaboration between the Nez Perce tribe, whose reservation was a part of the megaloads’ route, and non-native activists made the activism more effective.

After four years of activism and legal challenges, in 2017, a court agreement banned megaloads of a certain size, ensuring that Highway 12 was no longer a transportation option for oil companies. This made it significantly harder for oil companies to use megaloads and extract oil from the tar sands.

The other major experience that Grosse discussed was in Santa Barbara, where activists tried to prevent new fracking permits from being issued via a ballot measure called Measure P.

The organization she was a part of, the Santa Barbara County Water Guardians, got 20,000 handwritten signatures to get Measure P on the ballot in only three weeks.

“This messaging about water was really strategic,” Grosse said. “Water has the ability to be bipartisan. They [didn’t] have oil or climate change in [the messaging].”

She spoke about how the leaders of the movement, including herself, were told by old-guard environmentalists to work with the Democratic Party. However, in doing so, the structure of the movement changed, to be more hierarchical and less community-focused. Grosse said this decreased the empowerment and involvement of those who had been with the movement since the beginning.

The ballot measure ended up failing, and Grosse cited a general lack of support from Latinx voters as the reason why, due to major mistakes from the movement leadership when communicating with the Latinx community. Leaders neglected to include existing Latinx organizations in the process and failed to incorporate issues they cared about into their messaging.

Despite the electoral loss, Grosse argued that the measure still produced some successes. After Measure P, there have been no new major oil projects in Santa Barbara, and new stringent emission limits have been implemented in the county.

Grosse concluded the talk by giving some advice about activism, explaining that it’s important to make activism fun and creative. She provided examples from her personal experiences within movements, including the creation of an inflatable oil pipeline to carry around at protests, salsa dancing to keep warm and dressing in ballroom gowns and dancing to stop megaload transports.

She also emphasized that people need to find common ground and creating relationships with people can go a long way for a movement.

“Despite the rhetoric that we hear in national news, most people do really share core values when we talk about them in non-politicized terms,” Grosse said.