Revisiting our neighborhood’s student housing policy

April 14, 2022

Every year, students from St. Paul’s agglomeration of colleges embark on a search for new housing. Many students who have lived in dorms enter the private rental market for the first time in their lives. Houses, duplexes and apartment buildings all fill up.

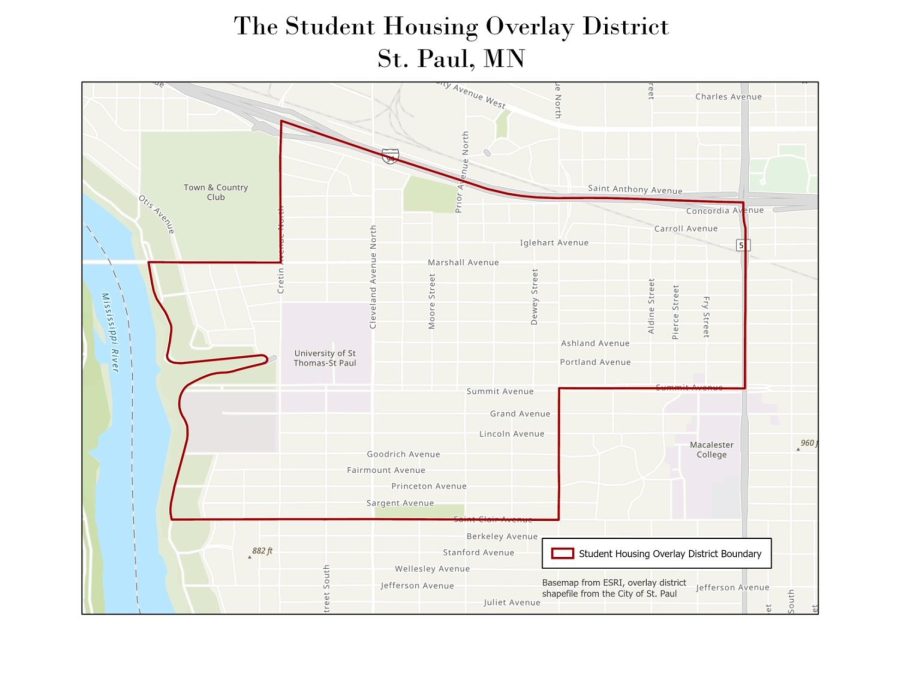

For students searching for housing in the area around the University of Saint Thomas (UST) — including areas right to Macalester’s north and west — there is a policy that systematically limits their living options. This is the Student Housing Overlay District.

The Student Housing Overlay District was passed by the City Council in 2012, requiring landlords to register houses and duplexes as student dwelling if there will be 3 or more students in the unit. With this registration system in hand, the city enforces a requirement that no two houses or duplexes for students can be within 150 feet of each other.

Both in principle and in practice, the overlay has problems. The policy comes from real concerns from other neighbors that must be addressed. But the overlay unfairly targets student renters and imposes real burdens on them, a shortcoming that calls for revisiting the policy.

The policy has its origin in neighborhood tensions between UST student renters and homeowners in the area. Through the 2000s, St. Thomas’s student population had been growing faster than its on-campus dorm capacity, and the University only controlled enough dorms to require that students live on campus for one year. As a result, abnormally high amounts of students were moving into houses in the neighborhood.

“There are homeowner neighbors that have said to me, ‘St. Thomas outsourced its housing problem to the neighborhood,’” Amy Gage, the Director of Neighborhood Relations at University of St. Thomas, said.

Some residents near St. Thomas felt that their blocks were being overwhelmed by student housing. In an influential report written in 2001, the law firm Smith Partners wrote that having more than 30% of households become rentals (rentals of any kind, including but not limited to students) would risk “disinvestment and decline.”

It was clearly true that some students were infringing on the well-being of their neighbors. Residents testified to the city council about dealing with drunken tomfoolery and late-night noise problems. Some rental houses with distant landlords and careless students were not being well-kept, deteriorating the block’s appearance.

These problems matter to homeowners. “Curb appeal can make a big difference on the next door neighbor’s property value,” Deanna Seppanen, director of the Macalester High Winds Fund, said.

But while the causes of neighborly discontent were legitimate, the policy that was crafted in response seemed to unfairly and undemocratically target students.

Efforts to institute the policy were supported by neighbors in groups like the West Summit Neighborhood Advisory Council and the Macalester-Groveland Community Council. In June 2012, the city council held a public hearing and voted on the policy. Many residents testified in favor of the ordinance; a few testified against it. There were no students there, because St. Thomas’s school year wasn’t even in session. The city council approved the policy in a 5-2 vote.

Today, St. Paul has a Frequently Asked Questions page about the Overlay District. It seems to reflect how some of our fellow citizens and policymakers perceive students as neighbors:

“The ordinance is created to address the concentration of the number of student houses on any given block in the overlay district. It is aimed at the idea that beyond a certain tipping point, our neighborhoods become destabilized.”

The ordinance singles out college students as a group that cannot be too prominent, lest they destabilize the neighborhood.

Bill Lindeke is an urban geographer and blogger who was serving on the St. Paul Planning Commission when the overlay district was passed.

“It just struck me as a kind of policy I don’t like, which specifically targets a group of people over something they have no control over,” Lindeke said.

Beyond the attitudes toward students seen in the language and creation of the ordinance, the actual policy is harmful to student renters. It seems well-designed to prevent students from “destabilizing neighborhoods.” But it’s poorly designed to help 20 year olds with student debt and no car find a place to live.

One result of mandatorily spreading out student housing is an increase in transportation costs for students everywhere. Most students would naturally prefer to live closer to campus and have an easier commute. However, requiring that all student housing be rationed in 150-foot portions means that students have to make further, longer commutes — or switch to otherwise unnecessary car commutes. That imposes individual costs on students, and social costs via pollution and traffic.

At the same time, this policy likely raises housing costs for students. There’s an extensive body of research which finds that strict land use regulations (such as single-family zoning) make housing more expensive by constricting the supply of housing available. For example, UCLA urban studies professors Michael Lens and Paavo Monkkonen found that low-density zoning segregates affluent people into their own neighborhoods by limiting the availability of housing, and economists Edward Glaeser and Edward Gyourko found that zoning regulations in U.S. cities generally make housing pricier than it would otherwise be.

The Student Housing Overlay District is similar to these kinds of policies: it chokes off the supply of housing that’s available to students. Doing so reduces the housing available in the most desirable, near-campus locations, gifting excess market power to the landlords that can rent to students near campus. So almost certainly, this policy makes students — many of whom are already incurring debt and living on thin finances — pay more for housing than they otherwise would.

The overlay district is not without benefits. A primary upside to the policy is maintaining a healthy mix of households in the neighborhood.

“I have homeowners near me, retirees, student neighbors, empty nesters, a house for adults with developmental disabilities, sober houses. There’s a mix, so our students get a more real-world experience with the overlay than they would if they lived in Dinkytown with nothing but other students around them,” Gage said. This can improve the neighborhood experience for student and non-student residents alike. As some of neighbors’ testimonials from years ago depict, a weak student-neighbor relationship really can harm the neighborhood.

The fact that the overlay district has upsides, however, does not necessarily justify its existence. The policy comes with substantial downsides, and the downsides — higher rents and further travel times — fall primarily on students.

St. Paul is not the only place that has struggled with student-neighborhood relations. In February, neighborhood members in Berkeley, California nearly forced UC Berkeley to reduce its incoming class size by a few thousand students (state lawmakers were later able to ameliorate the situation). A chief concern was that there wasn’t space for students in the neighborhood, and that they were creating a nuisance to neighbors. This would have forced thousands of young people to lose an opportunity to study at one of the world’s premier public institutions.

The case of UC Berkeley is one far more severe than that of the Student Housing Overlay District. But I fear that it reflects a similar, zero-sum worldview, in which incumbent homeowners must defend their neighborhood from the next generation of residents. Students eventually grow up, and when they do, they become a very important component of our future.

Additionally, many of the issues that the overlay was designed to address need not be addressed by constricting the availability of student housing near college campuses. A major cause for neighborly discontent was that the UST student body had been growing without adequate additions to on-campus housing. Addressing this dorm shortage probably never required the overlay district in the first place. Nevertheless, it’s no longer a problem: in the past few years, UST has invested in building new dorms and outfitting existing ones, giving them enough dorm capacity to implement a two-year on-campus residency requirement for the first time.

There are also fairer solutions to address other problems that led to the overlay’s creation. If students are partying too much and acting as nuisances to their neighbors, then those neighbors should work with the school and their students to resolve the conflict, or work to ensure enforcement of our city’s noise ordinance. If absentee landlords are leaving their properties overcrowded and under-preserved, then we should pass regulations that demand more of landlords. As then-Councilmember Melvin Carter said during a 2012 City Council meeting discussing the ordinance, policies should focus “on a set of behaviors rather than a set of people.”

St. Paul’s many higher-ed institutions offer an incredible opportunity for mutually beneficial interactions. Students spend many hours working and volunteering in this city, and many of them eventually settle down here. And it goes both ways — non-student residents offer students opportunities to engage with the Twin Cities and gain meaningful experiences. These interactions make our city better.

“Without the schools that we have, St. Paul would be a pretty desolate place,” Lindeke said.

So it is a subtle but painful indignity for our neighbors to inscribe city policy that treats students as lesser. Students are capable of addressing problems, but that’s not the message sent by writing policy that only imposes burdens upon students.

Neighbors can meet students on equal footing and collaborate on a better policy instead of one that comes at students’ expense. “It’s a relational thing on both sides, it’s all about getting along with your neighbors. That’s not always easy,” Seppanen said.

Certainly, a college that grows has a responsibility to accommodate that growth and build places for students to live, and students have a responsibility to act as members of a neighborhood community. Residents of our neighborhood also have a responsibility: to treat students as real community members. As is, the Student Housing Overlay District isn’t accomplishing that. It’s time for reconsideration.

Joseph • Apr 20, 2022 at 3:12 pm

While I agree with this opinion piece (mostly). This comes from the same publication that favored rent control. Seems hypocritical to oppose government intervention on one side and favor it on another.

Zak Yudhishthu • Apr 20, 2022 at 9:47 pm

For what it’s worth, the rent control piece was written by my colleague at the Mac Weekly, not myself.

But either way, I don’t think that holding those two stances is hypocritical, because it doesn’t make much sense to judge public policy based on a general principle of whether or not we like government intervention. We should instead judge public policy case-by-case, based on its impacts.