Outside the core curriculum: marginalized voices in topics courses

September 30, 2021

At Macalester, topics courses are a way for professors to cultivate classes based around their current research focuses, with complete autonomy over the sources and content they include. The classes are not a part of the official department curriculum and do not have to be approved by the Educational Policy and Governance Committee (EPAG), which is responsible for reviewing changes in course offerings.

The Macalester Registrar’s website describes topics courses as classes that are designed to accommodate the interests of students and faculty regarding current issues in the subject area, or to offer an experimental course that may later become part of the curriculum. In the fall 2021 semester, 54 topics courses are being offered at Macalester.

The simpler approval process for topics courses allows professors to teach classes with content that they are passionate about and affords them flexibility when it comes to the resources and ideas included in the courses. For some professors, that means teaching classes that bring in a variety of different perspectives and incorporating their research into the course content.

One of this semester’s topics courses, Native Americans in Popular Culture is taught by Assistant History Professor Katrina Phillips. The course is cross-listed in the history and media and cultural studies departments at the 200 level. It aims to examine the representation of Native Americans within pop culture, as well as how non-Natives have appropriated Indigenous imagery and established harmful stereotypes.

Phillips draws on her personal research on the part that Indigenous historical pageants have played in history, as well as from articles she has come across during her education. Part of her process when creating this course was diving deep into sources from the library, in an effort to develop more comprehensive course content.

“I’ll get links to sources from my dad,” Phillips said. “He knew that I was teaching this pop culture class and he started sending me links about Native actors who are in film and television. He’ll send me links to music and things like that.”

Showing students what it really means to study Indigenous peoples and understand the prevalence of harmful imagery and stereotypes is extremely important to Phillips, and this course highlights a lot of the work Indigenous artists and creators are doing to counter the conventional ideas seen in media. She described teaching the class as similar to peeling an onion; students are able to get to the heart of the matter and engage in more difficult conversations after peeling back the first shiny layer of the traditional historical narrative.

“It sometimes feels like there is a lot of pressure, because I do teach the history of historically excluded populations,” Phillips said. “Native people are so rarely included in a lot of curricular conversations.”

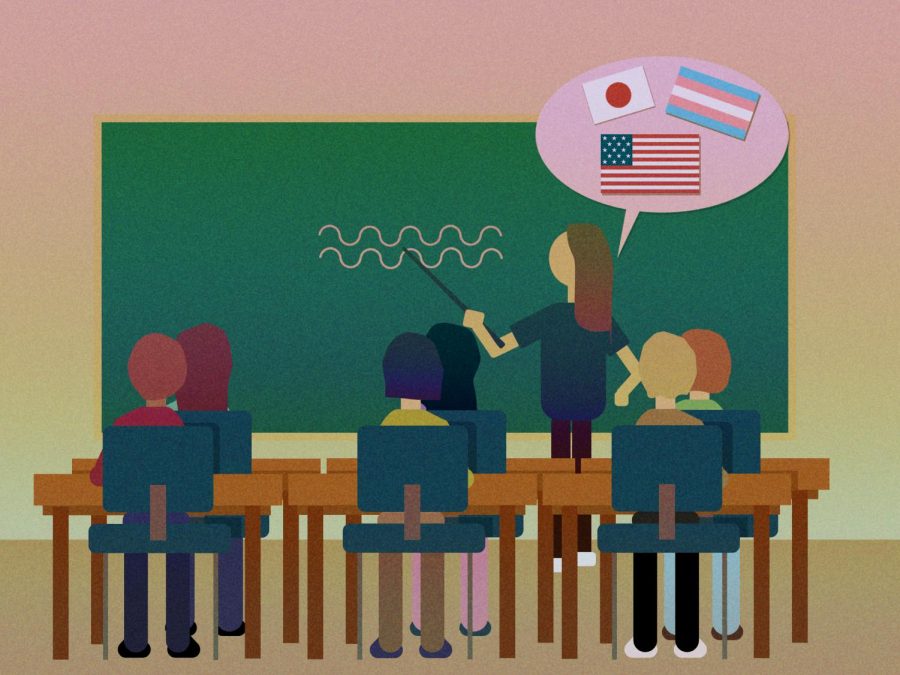

DeWitt Wallace Professor of Asian languages and cultures Satoko Suzuki is a specialist in Japanese linguistics, specifically language and gender, language ideologies and media representations. She is currently teaching a topics course called Language and Identity in Japanese, Asian American and Other Communities. Suzuki has been a part of the Macalester staff for over two decades and has seen her interests grow over the years.

“During the past year I was on sabbatical, and so I thought I wanted to develop new courses,” Suzuki said. “This is one of them. This reflects my research interests, which is how people use language to express their identity.”

Suzuki wants to include a more personal take on the subjects she teaches, focusing on relating language to identity. The first reading she assigned for the course was an essay called “The Triangle” by Indian American writer Jhumpa Lahiri, talking about the relationship between the three languages she speaks.

Suzuki’s course syllabus also includes an interview assignment where students are required to interview someone about language and how it relates to their identity. She said that a lot of her students are taking her class because they either are multilingual or they know someone who is and want to explore that. This contributes to her desire to teach students about personal stories, rather than just academic articles.

“The syllabus also includes reading assignments that I have not read yet, but I’ve seen the title and then that [article] looks really interesting,” Suzuki said. “So I want to learn about them myself too. I want to learn about them with my students.”

Each of the professors has their own way of keeping their classes engaged in the course content and discussions. Part of Phillips’ lectures is a guiding question for each day, which helps to direct the conversation if students are unsure of where to start. Suzuki has pairs of students lead class discussions and create content questions based on the readings due that day, and finds that discussions are sometimes more enriching when students lead than when she does herself.

This is Assistant Professor of media and cultural studies Tia-Simone Gardner’s second year of teaching at Macalester. Gardner taught Cultural Politics of Differences during modules one and three of the 2020-2021 academic year. She is teaching two sections of the course this semester.

Gardner sometimes finds it difficult to balance the foundational and background material necessary for the course while also including more contemporary readings and sources. The wide variety of students and their varying levels of background knowledge force her to adjust her expectations for the class depending on the dynamic her students create.

“I think sometimes it can be scary and intimidating to include things you’re less familiar with,” Gardner said. “But I’m happy to learn alongside students, because I think there’s a lot that I don’t know, and so I try to think very broadly with things.”

Gardner’s background is in gender studies, with a focus on Black feminism and critical race theory. She constructed the course by centering on the foundations of the subject, how race, gender and national identities operate and building out from these base ideas.

“My hope is that [my course] asks people to question their relationships with places and other people,” Gardner said. “What that looks like is always a surprise.”

She finds the course to be very dialogic, with her both answering students’ questions and asking them herself, and she hopes the class will help her students develop critical thinking skills that they can utilize in any learning environment, regardless of their field of study.

Visiting Assistant Professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies Myrl Beam’s course focuses on talking to people that have lived experience with the topics the course covers, for a more immersive experience. Beam teaches Telling Trans Stories: Queer and Trans Oral Histories, which partners with the Tretter Trans Oral History Project, a program based out of the University of Minnesota.

Beam describes the course as an experiential course where students both learn about oral history methods and get to work on an existing oral history project, ideally conducting oral histories themselves for donation to the Tretter Collection at the end of the semester.

“The experiences of trans and gender non-conforming people within the written archive is absent or only present as a problem to be encountered by powerful institutions,” Beam said.

According to Beam, oral history, in particular, is a helpful source of information about activism around trans issues, as well as a more robust and fabulous understanding of people’s experiences. He described the story told about trans and gender non-conforming people as flat and damaging, thus making oral history the perfect chance to get a better sense of gender transgressive strength.

“There’s often a really interesting fascinating mix of trans or non-binary identified students who know a lot from their lived experience and people who might be completely new but are really strongly interested in allyship,” Beam said of his courses centered around queer and trans issues.

According to a number of topics course professors, students come into topics courses with extraordinarily varying degrees of knowledge about the subject being taught, which is partially because topics courses rarely have prerequisite classes. From being a part of the communities that the class talks about, to having touched on the subject briefly years prior, students usually have vastly different perspectives to offer.

Phillips and Suzuki have both found that most students take their topics courses because they are interested in learning more about the subject matter and recognize the importance of the issues being discussed, not just because they are looking to fulfil a course requirement. This sentiment was echoed by Gardner and Beam, who have found a broad diversity of majors, interests and background amongst the students in their topics courses.

Beam is part of the department of women’s, gender and sexuality studies, which is composed of only two professors. This affords him even more freedom with the subject of his classes than topics courses allow on their own. However, even in larger departments like history or Asian languages and culture, topics courses permit professors to pull on their varying areas of expertise when they teach a class, creating a different experience for students than a class in the core curricula.

“I think topics [courses] are often gateway drugs,” Beam said. “They open a door into a new field.”