Way back at Mac: 9/11 through our coverage

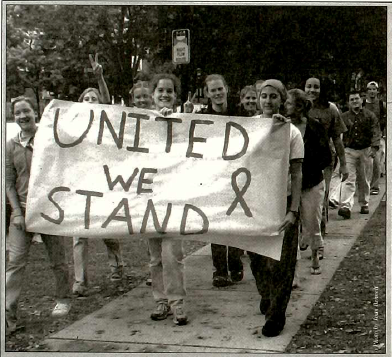

Excerpt from the Mac Weekly Sept. 21, 2001 issue. The original caption reads, “Macalester athletes and other students participate in a march to show support for victims of last week’s tragedy, including people of Middle Eastern descent who have been targeted.” Courtesy of the Macalester Archives.

September 16, 2021

Last Saturday was the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, which many marked as a day of mourning and remembrance. Others marked it as a day for war hawking and gaudy patriotic displays. At The Mac Weekly we decided to dive into our archives and examine how the Macalester community reacted and opined in the days and weeks after 9/11.

Macalester’s first issue after the attacks focused more on students arrested at a party than 9/11 itself. Almost three-quarters of the front page is dedicated to coverage of two students who were arrested after a noise complaint. The other quarter, however, did mention two students who spent their lunch hour holding signs reading “No Violent Retaliations.”

In their initial issue after the attacks, page three of the Weekly featured reactions from Macalester students with personal ties to New York City. Katy Forsythe ’02 described waiting hours to hear that her mother, who worked across the street from the World Trade Center, was safe. Forsythe also had two friends who worked in the Towers. They were missing and presumed dead at the time.

Both Forsythe and Lucy Cherkasets ’03, another New Yorker, felt unsupported by the Macalester community following the attacks. The two wore black to mourn the tragedy and reported that some classmates made fun of their decision or told them to “get over it.”

“I came [to campus] looking for community, I came looking for support,” Forsythe said. “But today there was nothing.”

Beyond a lack of support from classmates, there was also a lack of institutional support from the college. According to Cherkasets, Macalester was the last school to cancel classes on 9/11 (neither she nor The Mac Weekly give further context about this).

“[Cherkasets] felt that President McPherson ‘was patting himself on the back’ when he said that he did not take class cancellation lightly in his short speech in the Chapel on Tuesday,” the article said.

Students also noted the demonization and vitriol most media slung at Muslim and Arab people. One anonymous Macalester student feared for their family’s safety as a result. The two students who held the “No Violent Retaliation” sign on the corner of Grand Ave. and Snelling Ave. said they received many shouts which were unsupportive.

In an issue published on September 21, 2001, the Weekly’s front page headline reported that two Jordanian students received hate mail to their Macalester PO boxes. According to the article, the note, which was scrawled on the inside of the envelope, told the two students that they had no place at Macalester or in the U.S..

“In the heat of the moment we took it as ‘you’re not even worth the piece of paper,’” one of the students the letter was addressed to said.

The two students reported the letter to the school, and worked with then-Dean of Students Laurie Hamre to find support for not only themselves but other international students at Macalester who were affected by the contents of the letter. The article said that the college offered supervised trips to Target and promoted a buddy system so that students didn’t walk alone.

In a later issue, the Macalester College Student Government (MCSG) Executive Board responded to the incidents of hate mail. The board called the hate mail “deplorable,” and said that those acts will not be tolerated.

“Targeting people over their ethnicity and religion goes against every principle on which this community is based,” the board wrote. “These acts were cowardly and low. Those responsible for them should reconsider why they chose to come to Macalester.”

Targeted hate crimes like these letters spiked in the wake of 9/11. The number of hate crimes against Muslims jumped from 28 reported in 2000 to 481 reported in 2001. The U.S. government enacted huge surveillance operations in any and all Muslim spaces including mosques, student groups, civil societies and businesses. They passed the PATRIOT Act which disproportionately targeted Muslim people, and, broadly, Muslims in the U.S. were placed under a panopticon of surveillance, suspicion and hate.

Unlike many media outlets, The Mac Weekly and most at Macalester did not react with violence, Islamophobia or hatred. In contrast to reporting by the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other outlets, The Mac Weekly spent its journalistic time on the effects of the attacks on Arab students, New Yorkers, and the community as a whole.

A Weekly editorial said that while it was great that Macalester students discussed how the media was demonizing Arab and Muslim people, they must recognize that this concern is not universal outside of the Macalester bubble.

“It is important that we support those in this community and outside of it who may be affected by retaliation,” the Sept. 14 piece read.

In the issue published on Sept. 21, a page of the paper was devoted to comments from Macalester faculty, staff and students as they processed the events of the previous week.

“As a teacher, I’ve been concerned about my students and have encouraged them to keep talking, keep feeling whatever it is they’re feeling, keep listening respectfully to one another,” psychology professor Joan Ostrove wrote.

“Terror like the unparalleled tragedy of September 11, 2001 will stay with us for a long time,” Bibek Pandey ’02 wrote. “I only hope the world leaders make sound judgements and scrutinize possible consequences before taking any actions.”

Eileen McNamara described in WBUR how she uses the coverage of 9/11 in her college journalism classes as an example of how journalists should not report on an event.

“It is easy to forget two decades on how much a compliant press corps contributed to the patriotic fervor and uncritical thinking that helped launch the disastrous wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in response to the attacks,” McNamara wrote.

McNamara also mentions that there were journalists who questioned then-President George W. Bush’s assertions about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and eventually the war. Macalester students and The Mac Weekly appear to have agreed with these journalists. Their activism and coverage in the weeks after the attacks demonstrates concern for “the victims of last week’s tragedy, including people of Middle Eastern descent who have been targeted,” the Weekly wrote.

In addition, the Weekly’s editorial on Sept. 21, 2001 is titled, “The propaganda machine: irresponsible media leading the call to war.” Within their editorial column, the Weekly criticizes examples like Ann Coulter, a conservative pundit, and reactionary radio censorship in the aftermath of the attacks to describe problematic media decisions after 9/11. They also call on Bush to stay above the “raw emotion that can rule a mass of people.”

The Mac Weekly also published a number of opinion pieces and letters to the editor which graphically and problematically described how Macalester and the U.S. should react to 9/11.*

There were several students and alumni who advocated for the war that would ultimately ensue, calling for swift actions of force and protections of idealized American values of freedom and equality. Another described their outrage as they processed what happened and feelings of anger towards members of the Macalester community who advocated for a peaceful response, not reactionary war.

Later, in October, students staged a walkout to protest Bush’s decision to bomb Afghanistan. Over 200 students participated in the protest. One student wrote in an opinion piece in the Weekly that America should not fight a war against innocent people, drawing comparisons to America’s genocide against Indigenous people— the Diné (Navajo) Nation in particular.

Some students at the protest like Dan Ganin ’04 believed that retaliation such as this would lead to greater hatred of the U.S. in Afghanistan.

“Killing innocent civilians with the hopes that we may somehow stumble upon the terrorists after killing lots of innocent bystanders is just going to foster more hatred against the U.S.,” he said.

Others protested because they felt the media was misreporting the bombings and situations in other countries after 9/11. They were correct. In 2004, the New York Times apologized for their miscoverage of 9/11 and the aftermath, in particular their misreporting on Iraq. There are a number of other examples including cable news reports which did not fact check statements from Bush administration officials like then-Vice President Dick Cheney and late night shows airing unfounded reports of al-Qaeda members dancing on rooftops in New Jersey after the attacks.

Twenty years later, the echoes of 9/11 continue to reverberate through the world and Macalester’s campus. By Aug. 31, 2021, the U.S. ended its official military presence in Afghanistan, closing one of the longest overseas wars in U.S. history. Though the official withdrawl is complete, anti-Arab and anti-Muslim hate continue in America; the patriotic displays at sports games and country music concerts, made commonplace after 2001, continue and grow. Jordan Pender ’02 wrote in The Mac Weekly about the warped sense of justice in America after 9/11.

“War on Afghanistan, or wherever we decide to wage it, will not bring back the kids who were riding to the top floor of the World Trade Tower,” Pender wrote. “But it may cause the death of other children in distant lands.”

*Editors’ Note: We decided to not quote some inflammatory and harmful statements. Macalester community members who wish to read further can find original articles from The Mac Weekly in the college archives. We also chose not to include full names of students who received hate mail to avoid retraumatizing these survivors.