Macalester’s culture, communities and the path forward

April 1, 2018

Content Warning: Matias Sosa-Wheelock’s death affected all members of the campus community differently, depending on individual experiences that night, in the days following or with mental health and mental healthcare at other points in their lives. This special report includes in-depth reporting on the response to Sosa-Wheelock’s death as well as the state of mental health and healthcare on campus more broadly. While we have refrained from including graphic details, it may nonetheless be difficult to read. Before beginning, please be aware.

For a list of support resources on and off campus, visit this link.

At colleges and universities across the United States over the last decade, levels of anxiety, depression and suicidal thought among students have increased dramatically. Macalester is no exception.

“A metaphor that some student used to describe life at Mac is that we’re like ducks sitting on the surface of a calm lake. We look really relaxed, but underneath we’re paddling furiously,” political science professor Lisa Mueller said. “I thought that was really descriptive of how many of us feel.”

That struggle to stay afloat seems to be tied directly to the struggle to stay afloat in Macalester’s academically rigorous environment.

“A lot is expected of [Macalester students], and a lot of those expectations get internalized,” Director of Counseling Ted Rueff said. “And to the degree that they are not all met, I think it puts our students in kind of a vulnerable position.”

Religious studies professor Erik Davis ’96 agreed, but said that many of those expectations – however strong – are implicit.

“It’s the unspoken expectations that are, I think, so damaging,” he said. “Pretending that the world is not different from what it was in the 80s, or that the next twenty years aren’t going to be very dramatic in terms of things like climate change, those are ways of setting up expectations that are illusory for you.”

From the external pressure of professors encouraging students to sacrifice their well-being to complete coursework to the internal pressure to perform that Rueff highlighted, students consistently pointed to the academic demands of the college as a primary factor in mental health challenges.

“Macalester is an Ivy League [school] with an inferiority complex,” Liz Roten ’18 said. “We have to go extra, extra, extra on everything… I wouldn’t have come to Macalester if it wasn’t a high rigor institution. But I think there needs to be [a better] balance.”

“I think that people at Macalester want to push themselves as hard as they possibly can, even harder than they should, and that’s really unfortunate,” Voices on Mental Health co-chair Kendall Dickinson ’18 said. “There’s not a lot of real push to actually take care of yourself, it’s more about just powering through.”

“A lot of my classmates who graduated did not necessarily have th[e] skills to prioritize their mental and emotional well-being,” Voices on Mental Health co-chair Tess Huber ’18 said. “Maybe they have a fancy job or an internship or something, but a lot of them aren’t necessarily happy, and really, really struggled not being in this rigorous academic environment anymore.

“They knew how to do school,” she continued. “They didn’t necessarily know how to do other things because we require everyone to basically be a certain type of student.”

The effects of that attitude can be seen not only in how students take care of themselves, but in how they relate to each other.

“I think that we are also a very busy campus,” Chaplain Kelly Stone said. “And so it’s really easy to be so busy in our own life that we don’t slow down and pay attention to the people around us, that we miss opportunities to connect.”

When Chaun Ping ’21 arrived at Macalester in the fall, he was disappointed in the atmosphere he found.

“I find it a little bit morbid, because when you come to Macalester, you don’t see people smiling,” he said. “[This] is advertised as a close-knit community… but it’s not what I see.”

For students of color, Macalester can be particularly isolating.

“I do not think that my mental health problems are solely because of the fact that I’m a person of color,” Andrew Smith ’19 said. “But I do think [they are] definitely exacerbated by that fact… being a person of color on this campus is extremely difficult and, truthfully, in my opinion, dangerous.”

Smith and Ping’s experiences line regarding the campus community – or lack thereof – speak to a crucial point made by Rueff: that while academic stress can be a “contributing factor,” it is not likely in and of itself to trigger a mental health crisis.

“I think that in the process of an achievement mentality combined with a go-it-alone mentality, we’ve lost track of the benefits of interpersonal interdependencies and our willingness to be vulnerable with each other and support one another in that vulnerability,” Rueff said.

“I think a lot of Macalester students are invested in performing well, and in addition to that are engaged in lifestyle practices that don’t support their well-being,” he continued. “So they look pretty good on the outside, but on the inside are slowly coming undone.”

Davis agreed.

“I don’t want to commit the mistake of representing Macalester’s student body to them without any genuine understanding,” Davis said, “but I do sense that there are real issues on campus for many students of feeling isolated – individualized to the point where they don’t even know where to begin reaching out.”

Against that background, the infrastructure to support mental health at Macalester is not broad or deep enough.

“The therapists on campus, as far as I can tell, are working their asses off,” Davis said. “I certainly don’t want to be read as being opposed to the therapists on campus. But we clearly aren’t meeting the need.”

Rueff, from his position in the counseling office, confirmed that.

“It seems there are never enough [counselors],” he wrote in an email to The Mac Weekly. “In the past five years we’ve grown our individual counseling capacity at nearly five times the rate of student enrollment at the college… yet we continue to struggle in keeping up with the increase in demand.”

That increase in demand has been staggering during this decade. Health and Wellness has increased its face-to-face service offerings by 45 percent since 2012, and has barely made a dent in its waitlist for regular counseling appointments.

Rueff said that he has seen anxiety emerge as a “dominant” theme at Macalester and on college campuses more generally during his time at the schools, accompanied by what he characterized as a “perceived decline in student resiliency.”

“People [are] anxious about things I wouldn’t have anticipated their being anxious about twenty years ago,” Rueff said. “But I’m not blaming anyone for that. It’s not a fault in character or anything, it is a function of what’s in the air – in combination with how we’ve learned to cope with those variables.”

The numbers back Rueff up. Of the 26,139 undergraduate students at American colleges and universities who took the American College Health Association National College Health Assessment (ACHA-NCHA) in 2017, 62 percent reported feeling anxious while 88 percent reported feeling overwhelmed.

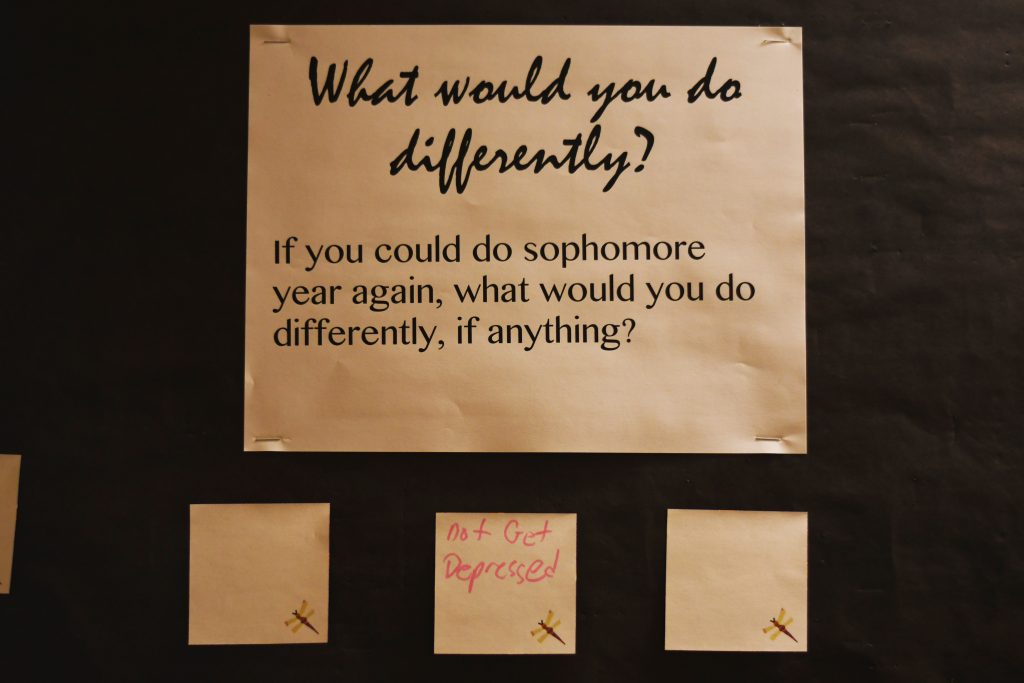

At Macalester, those rates are even higher. Of the 456 students who participated in the ACHA-NCHA last year, nearly 49 percent reported feeling depressed to the extent that it was “difficult to function” sometime during the past 12 months.

80 percent of Macalester students reported feeling very sad during that same time frame, 78 reported feeling very lonely, and 14 percent had seriously considered suicide. Those numbers were all higher than they were in 2009, and higher than the national averages.

Rueff pointed to the presence and effects of technology, rampant social and economic inequality and an ascendant “safety culture” that prevents children from traversing failure before coming to college, among other factors, as reasons for the increase in anxiety.

Those changes have been societal, and, for Davis, no amount of individual attention will be sufficient to handle the mental health crisis on college campuses.

“Basically the situation is, even if Macalester made emotional well-being its number one priority, I suspect there is not enough money to hire a sufficient number of qualified therapists to handle all the genuine need on campus alone, as individuals,” Davis said.

Davis recounted the story of Derek Black, the son of the founder of the white nationalist website Stormfront and a rising star in the movement, who was invited week after week by a Jewish group at his Florida college to Shabbat dinners until finally, after several years, he denounced white supremacy.

“That’s beautiful,” Davis said. “It’s a story of genuine human vulnerability, and opening and wonder. But can we ask every Jewish organization across the country to do that for every Nazi? That’s ridiculous. It doesn’t scale.”

“Many of these are individualized problems [that] need and require individualized attention,” he continued, “but many of these at least overlap with social challenges and problems that do not reside in the individual but reside in our practices and patterns of interaction.”

At a Cornerstone Forum on April 18, Macalester President Brian Rosenberg, speaking on mental health, sounded a similar note.

“I’m not convinced just throwing more counselors in the counseling office is working,” he said. “I think we are triaging right now and I think we need to find a way to treat the cause, not the symptom.

“I need to figure out what we can do and what kind of culture we [can] create inside and outside the classroom that can be healthier than it is now.”

Community, for Rueff and others, is the way out.

“To the extent that we make people feel part of communities and a necessary part of those communities, [that] they have a vital role to play and are valued in those communities,” Rueff said, “that’s really the work of suicide prevention right there.”

Davis agreed, but took issue with the how the concept of community is portrayed and thought of at the college.

“The problem with the word community is that we use it in ideological and representative ways,” Davis said. “We use it to describe the Macalester community. We use it to describe the community of LGBTQIA students on campus. We use it to describe the community of athletes. These may or may not be real communities.”

“When I’m using the word community, what I intend by it are the networks of relationships of genuine individuals and the actual interactions they have,” he continued. “It’s not just a place where people live or an identity category into which people fit, but it’s work. It’s action. It’s care. And it’s love.”

“If you want healing,” he said, “those things are non-negotiable.”

For students like Ping and Dickinson, Voices on Mental Health has been that active community. For Smith, it’s been the football team. Counseling groups – seven offered this semester, a record for Macalester – have also been met with a positive response.

The push for more counseling groups was driven by students, and, according to Davis, so will all of the most substantive solutions to the mental health crisis.

“[This] certainly expands beyond Macalester’s student body population, and, as a consequence, the solutions will have to be broader,” Davis said. “They can’t be limited to Macalester. And realistically and historically, they will be created, driven and instituted by students.”

“Practices of social transformation, trust-building, finding out what it actually means to love each other in public – these will be experimental,” he continued. “They will oftentimes be oppositional or confrontational to the existing situation. And these moments of experimentation will be tense. But they will be moments of potential growth.”

To Davis, that intentionally has very little to do with this institution or institutions at all.

“I refuse a vision of society in which our resilience and our ability to care for each other are dictated by and limited by money and budgets,” Davis said. “If we’re going to heal, transform, and grow, we have to be in control of that process.”

“Nobody is coming for us, to save us. And that’s scary, but that means that we have to do it for ourselves… and that’s where the hope comes from, I suppose.”

James Robertson • Sep 11, 2019 at 7:40 pm

I am impressed with this website , real I am a fan.

Diane James • Sep 10, 2019 at 1:34 pm

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read anything like this before. So nice to search out any individual with some original thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for starting this up. this web site is one thing that is wanted on the web, somebody with a little bit originality. helpful job for bringing one thing new to the internet!

Brian Martin • Sep 6, 2019 at 11:59 pm

I might also like to say that most people that find themselves with out health insurance are typically students, self-employed and those that are not working. More than half on the uninsured are under the age of Thirty-five. They do not sense they are requiring health insurance since they are young and healthy. Their own income is typically spent on houses, food, and also entertainment. Many people that do go to work either complete or part-time are not offered insurance through their jobs so they proceed without due to rising cost of health insurance in the states. Thanks for the tips you discuss through this blog.

Ty • Aug 12, 2019 at 7:02 pm

Thanks I needed this