In celebration of the current Women’s History Month, The Mac Weekly interviewed six of Macalester’s notable female alumni about their studies and careers. From the lab to social

justice, these women have lived impressive lives that inspire the current generation of Macalester women. We hope that this article will become the first in a series spotlighting impressive alumni during their respective history months.

Lois Quam ’83

Lois Quam ’83 is among the most notable female alumni of Macalester College. She was on Fortune’s list of the most influential women leaders in business three times and is the Chief Executive of the global health nonprofit organization Pathfinder, which is focused on reproductive health and justice. She was the head of former US president Barack Obama’s Global Health Initiative at the Department of State and was the founding CEO of the UnitedHealth Group sector, which provides services to low-income families in the United States.

Interested in ways people create social change, Quam pursued a political science major and a history minor. When looking back at her time at Macalester, she noted that her involvement in the school and community foreshadowed her future career. She was, for instance, an active member of Macalester’s student government, which was called Community Council at the time.

Quam became a student at Macalester only a few years after Roe v. Wade, the court case that legalized abortions in the U.S., was decided. Even as an undergrad, Quam was an avid women’s rights advocate, which led her to teach a January term course on the history of reproductive health in America.

She went on to write her thesis on the same topic.

“[Macalester] taught me how important it was to persevere and to be resilient for justice,” Quam said.

After graduating from Macalester, Quam went to graduate school and earned a master’s degree in philosophy, politics and economics at Oxford University and became a Rhodes Scholar. Alongside her work in the global health sector, Quam is the author of the book “Who Runs the World? Unlocking the Talent and Inventiveness of Women Everywhere,” which she is launching this week in celebration of International Women’s Day in the United States. In her work, Quam explores the importance of reproductive health and its role in unlocking women’s potential.

Quam believes that reproductive justice, which she defines as all women having autonomy over their bodies, is essential to the creation of a more just world. As her final remark, she urged all young women who have the privilege of choice to choose to follow their dreams.

“[Women must] be our whole selves and to find purpose in our life,” Quam said. “I have three children, [and have] done interesting work [because] I wanted to have both. I wanted to work and I wanted to have children. I think as women we can sometimes [forget] to pursue our dreams and so if I could speak to my younger self or to you, [I would encourage you to] pursue them. No matter what they are.”

Gaby Strong ’86

Strong.

Gaby Strong ’86 grew up in the heart of the American Indian Movement (AIM), a grassroots Indigenous rights movement with a birthplace in the Twin Cities.

An enrolled citizen of the Sisseton-Wahpeton/Mdewakanton Dakota Oyate, Strong graduated from the Red School House in St Paul. This school was one of the original “survival schools,” community schools for Indigenous preschool-12th grade students, created due to concerningly high dropout rates among Indigenous students.

“I always had that lens of Indigenous rights and social justice,” Strong said. “I had a very different life than most of the students there.”

And as far as she knew, Strong was the only pregnant student on campus, having two of her three kids while enrolled. She chose Macalester in large part for its accessibility and the financial aid she received. To make ends meet, Strong held multiple jobs during her time at Mac, including at her alma mater the Red School House and at the Indigenous organization Women of Nations.

“Financially, it was more accessible at that time,” Strong said. “I don’t think those kinds of resources exist anymore, I left Macalester only $1,200 in debt. It’s discouraging to see the kind of education that Macalester could provide [that] is not as accessible anymore.”

On campus, Strong was very involved in the American Indian Student Support Group (now Proud Indigenous Peoples for Education [PIPE]).

“There weren’t many students of color on campus [but Mac] had a really strong American Indian student support program,” Strong said. “I think there’s been a lot of shifts in what’s being offered in terms of American Indian student support. At that time, there was an actual office and staffing.”

After leaving Mac, Strong worked for 16 years less than a mile from campus at the Ain Dah Yung Center, which provides shelter, housing, and prevention services for Indigenous youth. Strong was a part of its founding, helping obtain the initial grant and serving as a counselor.

During her time at Ain Dah Yung, Strong rose in the ranks to serve on the board. With time, however, she started to feel her interests shift.

“I felt like I wanted to be able to address root causes of social issues and social justice issues rather than help people cope with those injustices,” Strong said. “I realized that there was deeper work that needed to be done.”

Strong transitioned to working with the NDN [Native Indian] Collective, an organization that defines itself as an “Indigenous-led organization dedicated to building Indigenous power.” Some of NDN’s core programming includes grantmaking, narrative amplification, lending and investing, policy and advocacy work, climate justice and power-building.

“No one [program] alone can really address the issues that our people face,” Strong said. “Most of the wealth that we know today was built off of our lands and on brown and black labor, exploited,” Strong said. “We look at [NDN’s work] as liberating wealth from the philanthropic sector and repatriating that wealth back to our people.”

Strong, NDN’s vice president as of Monday, March 4, has worked with the organization for four years.

In its short six years of existence, NDN has become “the largest Indigenous-led fund in history, in herstory,” according to Strong.

For college students looking to get involved in advocacy, Strong gives some advice.

“Know what your issue is, know what you want to accomplish, know who your allies are … ensure that whoever you’re involving are those that are going to be impacted the most by it,” she said. “You were born for this time. And if you were born for this time, there’s a role you play in it.”

Joan Velásquez ’63

For Joan Velásquez ’63, Macalester College opened her eyes to the world. Velásquez grew up on a farm in the homogeneous Protestant town of Hills, Minnesota, which lacked racial diversity and an assortment of worldviews.

While it was initially intimidating to move from a small town to the Twin Cities, Mac’s international student population allowed Velásquez to meet people she would never have met had she stayed in her hometown. The more she began to know students from other countries, the more her perspectives broadened and her interests shifted.

Velásquez was a sociology major. She knew she wanted to be a social worker when she arrived at Mac, but she also highlighted the importance of building a solid foundation in college that gives students the flexibility to go down many different paths in the future.

“People see a sociology degree and say, what is that worth?” she said. “But there are so many things you can do … it doesn’t close off possibilities when you start as a generalist.”

Velásquez was also passionate about student activism and was involved in the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA).

Velásquez graduated around the height of the Vietnam War. In 1967, inspired by John F. Kennedy’s mission, she decided to join the newly formed Peace Corps and was stationed in Bolivia for two years.

“Joining the Peace Corps [was] doing something very different from military service, something positive,” Velásquez said. “And that was a very exciting kind of alternative. You can go some other place in the world and hopefully make a positive difference.”

Upon returning from Bolivia, Velásquez earned both her master’s and doctorate degrees, working as a clinical social worker. She received a grant for a social work program that aimed to train social workers to work effectively with communities of color. Along with another Mac graduate, Velásquez ran various Latino learning centers and taught students. She was the only social worker in the program who spoke Spanish, staying connected with the Latino community even after returning home.

Eventually, she was hired by Ramsey County as a research director. She did program evaluations for social service mental health programs and other types of research.

In 1994, all her hard work culminated in her biggest project yet, the result of an unexpected setback. When Velásquez was just two years old, she contracted polio and was placed in an iron lung. With frequent hospitalizations, she was able to live a relatively normal life. But late effects reappeared, and Velásquez became too sick to work outside the home.

“There’s a whole lot you can do while lying in bed,” she told me. “In this day and age, when you have a cellphone and computer, it doesn’t matter where you are.”

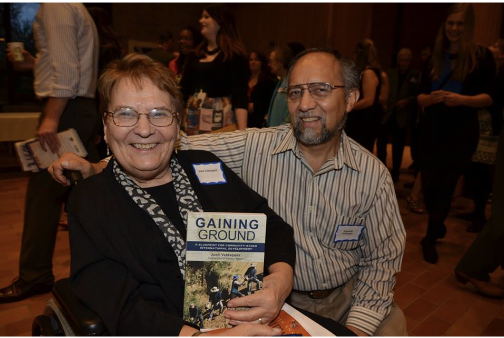

She and her husband Segundo co-founded the Mano a Mano International organization to address critical health issues in rural Bolivia. By collecting medical surplus in Minnesota and shipping it to Bolivia for distribution, Mano a Mano has since shipped over four million pounds of medical, school and construction supplies to Bolivia, with 700,000 Bolivians now having access to healthcare for the first time.

Macalester College helped Velásquez discover the values that most mattered to her. For us, as current college students, she gives some advice.

“I can’t overemphasize [this]: listen, observe, pay attention, come in trying to clear your mind of the sense that you already know something,” Velásquez said. “Try to understand as much as possible about different views of the world.” “What are your core values as a person? Passions? What interests and excites you?” she said. “Trust that … Something will emerge.”

Lisa Peterson ’81

Lisa Peterson ’81 fell in love with the lab environment in her time at Macalester, and has since pursued lab work throughout her life.

One of Peterson’s main reasons for attending Macalester was the opportunities it provided for undergraduate lab experience. Most undergraduates at larger schools were not offered lab opportunities, but Peterson had two: one at a University of Minnesota pharmacology lab, and the other synthesizing arc beetle pheromones as her Macalester honors thesis. Although the arc beetle experiments were a failure, the experience was crucial for Peterson.

“I really started graduate school with a leg up because I knew how to function in a lab,” Peterson said. “[And] I spent a year making gum, so I knew what it was like to have something not work.”

Macalester also allowed Peterson to embrace the variety offered by a liberal arts education. For instance, she made sure to take at least one non-science class each semester. Stretching herself this way taught her to write well and consider biases.

“It’s a liberal arts approach to life that [was] strongly nurtured at Macalester and has continued throughout the rest of my life, not just my career,” Peterson said.

With the encouragement of chemistry Professor Emeritus Janet Carlson, her Macalester thesis advisor, Peterson stepped out of her comfort zone by attending grad school out-of-state at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) for medicinal chemistry.

“I really wanted to go to a chemistry program that was at the interface of chemistry and biology, and back then the best place to do that was medicinal chemistry,” Peterson said.

She then pursued doctorate work with the stereochemistry of nicotine metabolism at UCSF and post-doctoral research at Vanderbilt University’s Center for Molecular Toxicology.

After her postdoc, Peterson took a job in carcinogenesis at the American Health Foundation in Valhalla, NY. Research there depended on grant money, and Peterson turned in her first grant proposal the day she went into labor with her son.

At the time, people were often suspicious of women pursuing research and academics; they thought this education was wasted on people who would become stay-at-home moms.

“My second advisor told me that he didn’t think I should pursue academics,” Peterson recalled. “Because if I have babies on my mind, I’m not going to be able to focus on research. And of course, he was a father of two children.”

Peterson, however, proved them wrong. Her initial proposal was accepted and her research was funded, which was rare, especially for new researchers. A few years later, Peterson was recruited to teach at the University of Minnesota. She started as an associate professor, and is now tenured. While teaching there, Peterson has researched how chemicals cause cancer. The past ten years, she has served as Program Co-Leader of the Carcinogenesis and Chemoprevention Program in the Masonic Cancer Center.

Peterson is now starting phased retirement and looking for the next branch of her career.

“I don’t know what it’s going to be yet,” she said. “But I’m looking to do something different.”

Peterson’s advice to current students is to not get stuck on a singular rigid career path.

“Be curious and explore things that interest you and try not to be just on a path,” Peterson said. “Students today think that they have to come out of college trained to do something. I think the meandering and the wandering that happens with a true liberal arts experience teaches yourself how to teach yourself.”

“Be curious and explore things that interest you and try not to be just on a path,” Peterson said. “Students today think that they have to come out of college trained to do something. I think the meandering and the wandering that happens with a true liberal arts experience teaches yourself how to teach yourself.”

Kate Ryan Reiling ’00

Photo courtesy of Macalester Athletics.

At Macalester, Kate Ryan Reiling ’00 majored in political science and minored in women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and Spanish. She also played soccer and studied away in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where she did work around labor rights and sweatshops. She went on to become a successful entrepreneur and to work in higher education.

After graduate school at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College, Reiling founded a successful startup game company. She describes the game itself, Morphology, as “three-dimensional pictionary.”

“[The game came from] this idea of how [to] be creative and silly together and have fun,” Reiling said. “It’s about figuring out how to build a business — because I was interested in that work — but also about designing something that brought joy and happiness and people together.”

The company, Morphology Games, went on to design other games, an expansion pack and an app. Morphology was even named Time Magazine’s #2 Toy of the Year in 2010.

A few years after working at Morphology Games, Reiling did entrepreneurship work at Macalester. She taught internet entrepreneurship as an adjunct professor of economics for a year, then worked with Jody Emmings, the current Director of Entrepreneurship and Innovation and Idea Lab, to build the Office of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Reiling and Emmings also redesigned the second floor of the library to allow for creative problem solving.

“Being part of a community that’s invested in the growth and the potential of human beings and the impacts that we hope those humans have on the world is inspiring,” Reiling said. “I loved the evolution of the program and [being] part of building something that I wished had when I was at Macalester.”

Reiling has done other work in higher education, informed by other experiences she had at Macalester.

While studying away in Bolivia, Reiling saw how the power of the drug trade and drug war impacted small communities, and how U.S. powers tried to transition the Bolivian economy without understanding the practical realities in Bolivia. She still carries these lessons about power and access.

“My work centers around thinking about education and the democratization of education, who has access to it and who decides what learning counts [as learning] … and what that says about power and privilege in society,” Reiling said.

In 2021, Reiling started to work at the African Leadership University (ALU), which aims to provide accessible high-quality education focused on entrepreneurship. ALU was founded by Fred Swaniker ’99. At ALU, Reiling serves as Chief Experience Officer. She manages a variety of departments, including the curriculum.

“[I consider how to] teach entrepreneurship without reinvesting in systems that we think need to be changed or torn down,” Reiling said.

At both Macalester and ALU, Reiling loved working with students.

“They’re so fun and hopeful and they want to make an impact in the world,” Reiling said. “[Students are] these super smart, talented, gifted individuals trying to make their way in a complicated time.”

Reiling’s advice to current students is to not think that adults have it all figured out.

“I think there’s a sense of, ‘oh, when I get to “x” point in my life, I’m gonna know things,’” Reiling said. “And the reality is you’re just gonna have a different set of questions. It’s important to answer the questions because the work is around discovery. But, I find that once you answer questions, more emerge … [It’s] somewhat disappointing and also very exciting.”

Christy Haynes ’98

’98, Haynes, and Stephanie Medwid ’99. Photo courtesy of Christy Haynes ’98.

Dr. Christy Haynes ’98 graduated with a chemistry major, a Spanish minor and a mathematics concentration. Today, she is the first woman to head the chemistry

department at the University of Minnesota, the Associate Director of the Center for Sustainable Nanotechnology and an associate editor for the peer-reviewed journal Analytical Chemistry.

Neither of Haynes’ parents attended college, and they were not supportive when their daughter decided she was going to be the first in their family to pursue higher education. Haynes chose Macalester because of its flexibility with financial aid that made college education accessible.

To Haynes’ knowledge, she is the first in her family to choose a career in the sciences.

“I felt drawn to it because it felt like you could do something that made a difference, but also there were lots of jobs and at the end of the day … coming from kind of a more financially insecure background, I was really drawn to something that was going to be employable,” Haynes said.

As a first-generation, low-income student, even with the generous financial support Haynes got from Macalester, she still worked 30 hours a week outside of school and graduated a year early.

“I definitely was envious of the people that were in the position to [join clubs and be involved with the Macalester community], which was almost all of my friends,” Haynes said. “But that wasn’t really an option for me.”

When speaking of her time at Macalester, it is clear that Haynes appreciated the professors the most. She spoke very highly of the Macalester chemistry professors who inspired her to pursue a career in chemistry. She particularly highlighted the influence of Professor Emeritus Rebecca Hoye, who taught her organic chemistry.

“[Hoye] was a really important faculty member in my life because she was a woman, a chemistry professor and had young kids while I was [at Mac]. She looked like she had it all, and it was important [for me] to see that,” Haynes said.

After graduating from Macalester, Haynes went to graduate school at Northwestern University, she got her masters of science in 1999 and her doctorate in 2003. When asked what Haynes wishes to tell her younger self or a female student at Macalester, she gave two main pieces of advice.

“Every time I was in a room or in a class or in a club or wherever, I kind of felt like, ‘maybe I’m not good enough for this,” Haynes said. “Maybe I don’t belong here. Maybe I’m not a real scientist.’ [Reorient that and say]: ‘Actually, it’s the frame that is the problem. It wasn’t built for me. It was built for me as a white person, but it wasn’t built for me as a first-gen woman who’s never had a science person in [her] life. The frame is the problem, I’m not.’”