As a student with an invisible physical disability, I am no stranger to the ever-present ableism that exists within society. I am used to dealing with intrusive questions about injuries, inaccessible buildings and constant accusations of faking my physical issues, as I have been dealing with these things for my entire life. I thought I already knew the extent of the ableism I would have to experience, but I was apparently incorrect.

Two weeks into this school year, I severely injured my right knee. As someone who is incredibly prone to injury, this event was not surprising, but it did have a large impact on my semester. For the first time in my life, I was on crutches, and my physical condition was visible and obvious. The way I was treated by others during this time was so foreign to me, so there must be something happening. The various ways that ableism manifests significantly interfere with how disabled people interact with the world.

Simple observations first: holding doors. While on crutches, people tended to go out of their way to hold the door for me, which just seems like something that decent people would just do for everyone else. However, while limping my way to class without crutches after rolling my ankle or hurting my hip, some people would purposely close the door in front of me and then mock me for faking an injury. Because I was injured in a way that was not obvious at first glance, some people determined that I did not deserve the basic respect of holding the door for someone who was less than five feet away.

When I had a visible physical issue, I was uncomfortable with how helpful people wanted to be. Going out of the way to hold a door for someone who is injured seems like a kind gesture, but it may not always come across that way. When I was injured, I could not put on my own shoes, but I could push the automatic door button or, later on when I was only using one crutch, open a door by myself. If someone waited at the door, holding it open for me while I was still 30 feet away, or even worse, ran in front of me to open the door, I often felt that the little bit of autonomy I had was being taken away.

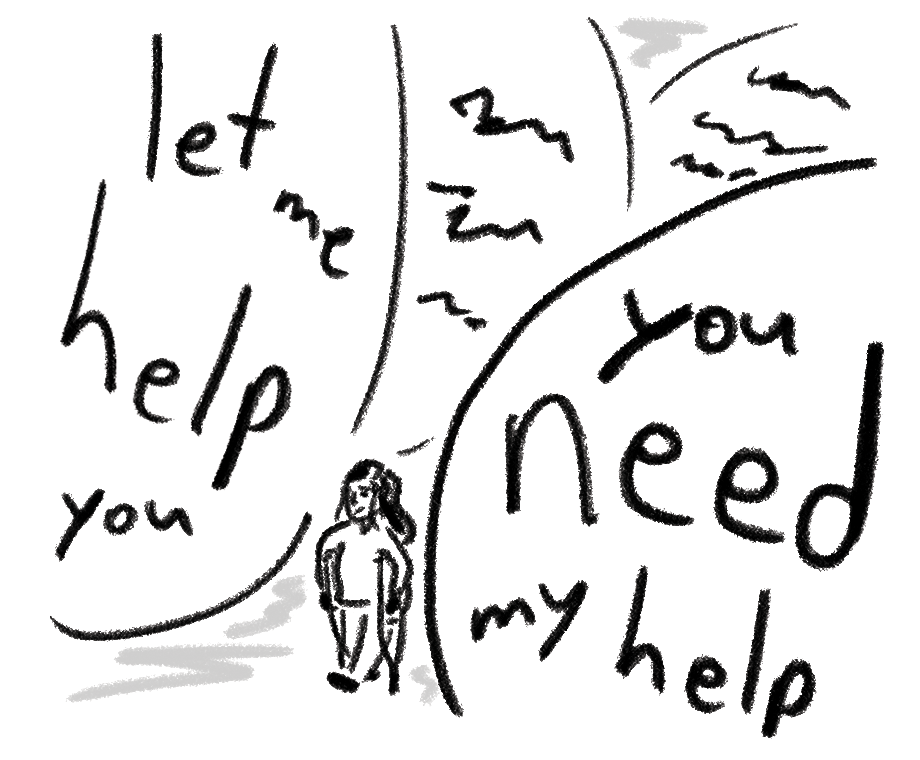

This is common occurrence within the disabled community. Many disabled people recount stories of strangers deciding it is okay to push someone’s wheelchair without permission. A wheelchair user could be completely self-sufficient, but that does not matter. Someone could just decide to “help” and the disabled person cannot do anything about it. If they complain, they are often told “just let him help! You need it, sweetie!” Too often, disabled people are seen as a pity outlet for able-bodied onlookers. Other people want to seem kind or look like they are doing a good thing, and the disabled person does not get a say in the matter.

It is one thing if someone asks for help. If I asked someone to hold a door for me, I would hope that request would be respected, whether I was injured or not, but the need for assistance should never be assumed. I know some people try to hold the door for everyone, but this is very different. There were instances where I was simply moving across the room, passing a door, and someone ran in front of me, almost tripping me to open said door. I was not even leaving, and this person assumed that I needed the door opened. This person proceeded to act offended that I did not thank them profusely and make use of their “kindness.” Why should I thank someone for nearly injuring me further so that they can feel like they are doing a good thing? Why should I apologize for going about my business and not adjusting my path to adhere to someone’s ego?

The societal perception is that all disabled people are helpless and incapable, and that no disabled person can exist in the world without endless assistance, but even when disabled people are independent, other people never want to leave them alone. With the application of basic accommodations, a lot of disabled people can live life to the fullest and participate in society. However, when disabled people find ways to navigate the world without relying on other people, like the use of service dogs, they often face extra discrimination. In the case of service animals, whether that be guide dogs for the visually impaired or medical alert dogs for cardiac conditions, they are often not welcomed within businesses. Even though it is illegal to ban service animals from an establishment within the United States, people still try to do so. Sometimes the harassment does not come from the business owner, but from the other customers who have decided that someone’s accommodation is an inconvenience to them. When disabled people do not need to rely on others, they are forced to endure even more harassment from those around them.

Ableism is ever-present throughout society, and this means that ideas and stereotypes are often pushed onto this minority. One of the biggest examples of this influence can be seen in labels. You may have noticed my use of the term “disabled people” throughout this article, which is intentional. This is a descriptor that has become surprisingly controversial, mainly because of able-bodied people trying to impose other labels onto individuals who do not want them. If someone wants to use these terms as a part of their identity, that is up to them, but a problem arises when certain terms become stigmatized against the will of the people who identify themselves with them.

The reason new terminology has not been widely accepted by many disabled people is the ambiguity of what the terms really mean, and the intentions behind their use. The terms “differently-abled” and “special needs” could imply that the person in question has abilities or skills that the general public does not possess. In conversation, these terms have become a way to make disability seem like a positive thing. These terms are often supported by able-bodied people, who often use the phrases to shame disabled people for “being too hard on themselves” and “looking at things too negatively.” Even worse, the term “handi-capable” is trying to do the same problematic thing to a term that is already problematic to begin with. The term “handicap” is incredibly ingrained into society, an example being that many people refer to accessible parking as “the handicap spot”, but the origin of this term is incredibly ableist. The word comes from the phrase “cap in hand”, referring to jobless people begging for money. This perpetuates the stereotype that disabled people cannot have jobs, so they take handouts and rely on able-bodied people to survive.

There are also those who argue that person-first language is necessary in this case, insisting on the use of “person with disability” rather than disabled person. The argument here is that being a person is more important to emphasize than being disabled, so the phrase must be ordered as such. Like all of the terms previously listed, this idea has been pushed onto the disabled individuals by able-bodied people. This is a personal experience that many disabled people, myself included, share. When talking about my disability, I have been told to use more positive terminology, on more than one occasion, and this comment has always come from an able-bodied person. I have never heard another disabled person insist on the use of person-first language, it is always an able-bodied person who claims to be an ally to disabled people. This insistence on the use of these terms is a form of cultural imperialism and is attempting to change our community to fit the perspective of the majority. But why should we listen to these pressures?

I am a disabled person. This is an integral part of my identity and should be treated as such. Why should anyone be able to tell me how I describe who I am? People don’t argue that LGBTQIA+ people should insist on being referred to as “person who is LGBTQIA+”, so why does it matter with the disabled community? Because able-bodied people want to feel bad for us and think that changing the “socially acceptable” term, to something that we disagree with somehow justifies their treatment of us.

Disabled people are smart, independent and capable individuals who have goals and inspirations, and we do not exist for others to take pity on. We deserve the same respect as any other person, whether our disability is visible or not. If I was having an issue, there are some basic respect points that I would hope people would follow: if I ask for help, please help out; if I want to do something myself, please respect that. I have a voice and can communicate if I need help or not. When it comes to terminology: please, listen to disabled people when deciding what terms you choose to use for them, instead of listening to ableist, cultural imperialist rhetoric.

The treatment of disabled people in society needs to change. There isn’t one particular area where the problems are isolated, these issues are systemic and wide reaching across all areas in life. Is there a clear solution? I’m not sure. But what I do know is that the disabled community cannot be silenced on these issues, the people affected need to be a part of the conversation.

Another person with an invisible disability • Dec 1, 2023 at 2:42 pm

Thank you so much for this

R • Dec 1, 2023 at 12:24 pm

It’s always refreshing seeing your articles on disability. When I first started using my cane, there was an immediate shift in how people treated me; I was no longer capable of autonomy in people’s eyes. I am sorry that you have had similar experiences, though I am glad to see someone talking about it publicly. I am disabled, and I am just as worthy of respect as anyone else. We shouldn’t have to beg for scraps. We deserve to be listened to, to have our needs met, to be included as a part of society instead of being relegated to the outskirts. Macalester in particular has a reputation for being very inaccessible to a variety of disabled people; this is an issue that needs to be addressed, and it needs to be addressed with the urgency and care that it deserves.