An economy to be worried about

November 3, 2022

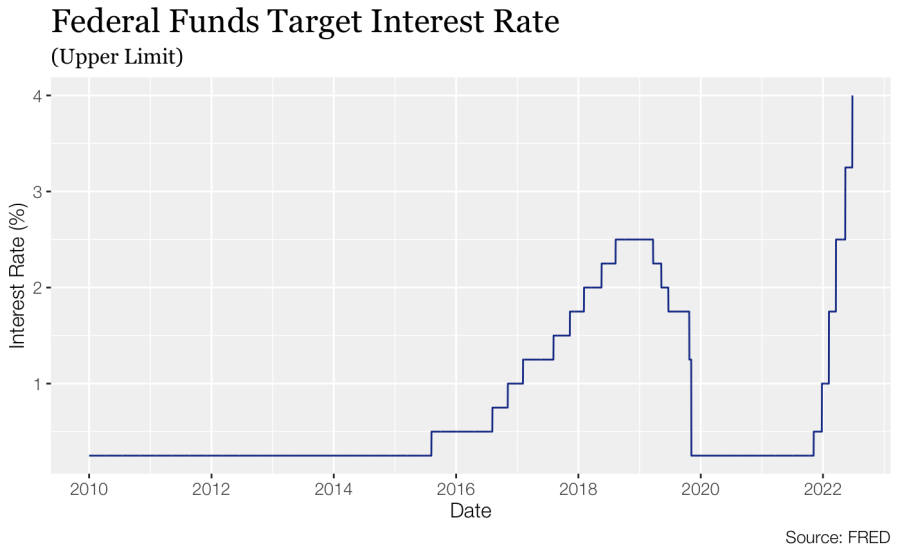

On Wednesday, Nov. 2, the Federal Reserve (Fed) announced that they will raise interest rates 0.75%, bringing rates to 4% after they started increasing from 0% in March 2020. This reflects the Fed’s efforts to combat inflation — prices today are over 8% higher than they were a year ago, which is the fastest price rise that the United States has seen since the early 1980s.

The meanings of these things aren’t always so clear to those less familiar with macroeconomics, who might not understand what interest rates really are and by what mechanisms they affect inflation and other pieces of the economy. But when we fully understand the implications of these economic undergoings, one thing becomes clear: we’re in an economy to be worried about.

First, we must understand what interest rates are, and why the Federal Reserve would use them to address inflation. The Federal Reserve controls the “federal funds rate,” which very specifically controls the interest paid by banks loaning to each other. More importantly, when the Fed raises the federal funds rate, there are ripple effects on the cost of borrowing money on a much larger scale. Businesses pay higher rates on loans, homeowners pay higher rates on new mortgages and everyone is incentivized to save more money instead of spending it on goods and services.

This process is already playing out in the nationwide housing market. Housing development is a risky, investment-intensive endeavor: developers have to borrow large amounts of capital to build new houses and apartments. When the Fed raises interest rates, developers have more challenges borrowing capital because loans are more expensive, and the demand for homes drops because mortgage rates are more expensive. The builders must build less.

As for the many construction workers whose labor builds our shelter, some of them will inevitably work less hours or become unemployed because there is simply less construction work to be done. This highlights an especially important effect of raising interest rates. When people are spending less money and businesses are investing less, unemployment will go up. In fact, this is an explicit aim of policymakers — they fear that wages will grow too quickly if the unemployment rate is too low, allowing for more consumer spending that will make inflation worse. The solution is to weaken the labor market by making more people jobless.

As a result, we’re facing increasing risks of a recession. If the Federal Reserve continues to raise interest rates, unemployment could become much higher and output could fall substantially. As the economist Adam Tooze writes, these risks are further multiplied across a web of global economic activity that is deeply interconnected but highly uncoordinated.

Here, the problem should feel more immediate to Macalester students. Attending or graduating college during a recession means having a harder time finding the jobs of your choice, and it means accepting lower pay for those jobs. Hopefully, we’re far away from a 2008-level recession, but ask anybody who graduated into that job market how their post-graduation job search went; research confirms that entering the labor market during a recession has long effects on peoples’ earnings and even long-term health outcomes.

And over the next few years, higher interest rates will likely cause other problems in our economy too. We can return to the housing sector, where, as we would expect, permits for new housing are already falling nationwide. Housing has been one of the largest contributors to inflation recently, with both rents and homebuyers facing steep price growth. One key driver of high housing costs is insufficient supply creating intense competition for places to live, especially in the metropolitan areas with the most housing demand. Addressing these housing problems will not happen without building more housing.

Yet perversely, higher interest rates cause builders to build less housing, which will serve only to exacerbate housing costs in high-demand cities. Although a decline in new homebuilding might help to address inflation, we’d be hard-pressed to call this a good long-term shift given our pervasive housing problems. And again, these concerns ring true across many different sectors: addressing inflation now likely means losing out on the investments that provide for an abundant future.

The Fed and other policymakers are in a tough bind right now — it’s not a great alternative to let inflation, which has also been reducing the value of workers’ wages, run wild. And to combat inflation, the Fed can do little aside from raising interest rates, so perhaps they must do this. However, this is a blunt tool that carries huge human costs, while also failing to address some of the key supply-side problems — not just in housing, but in energy and food too. Alternative policies from the government, such as targeted investment to address costly supply chain bottlenecks or tax increases on higher income brackets could help address inflation without the same downside risks or punitive distributional effects — but for now, the Fed is primed to continue on their path of raising interest rates.

Don’t let these complicated processes obfuscate the very real reasons for concern over the coming months.

Joseph P. • Nov 3, 2022 at 6:50 pm

Zak, thank you for your thoughtful essay. You might want to study the history of interest rates and their relationship to inflation, money supply and the time value of money. Furthermore, you might want to study the 1970s and 1980s as well as the 1930s in Germany. You see, Zak, money isn’t free. It has a cost. You spend your first 22 years in amazing (pseudo) prosperity based on artificially suppressed cost of money (interest rates). The piper has to be paid. The piper is here.

Zak Yudhishthu • Nov 20, 2022 at 6:10 pm

Hello Joseph.

I do agree that money supply has a relationship on inflation. But I fail to see the connection between the low interest rates of the 2010s and the inflation of today. The economy during the 2010s was in fact horribly understimulated, as represented by the dismal growth in nominal GDP and too-high unemployment. Now, I can see the case that large fiscal spending packages increased US inflation in the past two years, in addition to major supply shocks. But I don’t think that the longer-term trend of low interest rates before COVID is at all relevant.