Mac faith communities break new ground during campus closure

April 20, 2020

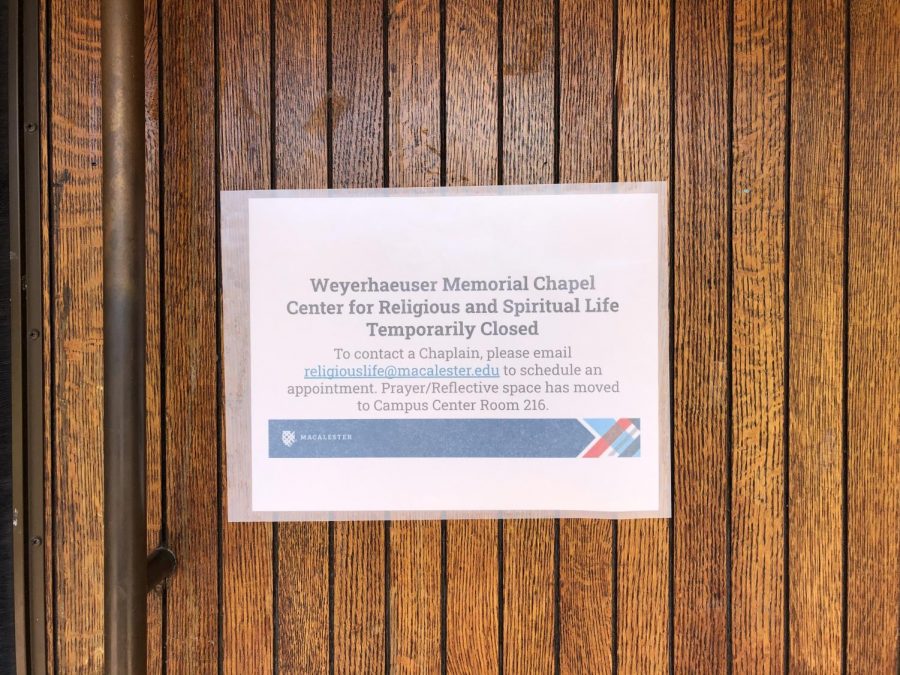

Since college facilities closed down after spring break, the doors to the Weyerhaeuser Chapel have been shuttered. Not only is the chapel normally the hub of campus religious and spiritual life, but it’s often busy with lectures, performances and spring sampler events. Most nights, golden light pours out of the floor-to-ceiling windows on the main floor, flooding the Great Lawn with its glow.

Now, the building is quiet and dark. It’s especially jarring in a season where many students are celebrating some of the most prominent and holiest holiday traditions of the year.

“You can’t celebrate these holidays absent the backdrop of what’s really happening in our human family,” Chaplain and Associate Dean of Religious and Spiritual Life Rev. Kelly Stone said.

At the same time, faith communities are looking to these traditions for answers and for guidance during a time of pandemic and mandated isolation.

“Ritual both gives you a sense of continuity with previous experience, but it also gives you a container to process your current experience,” Associate Chaplain for Jewish Life Rabbi Emma Kippley-Ogman said.

For Macalester Jewish Organization (MJO), the campus closure on March 30 backed right up to one of the most widely-celebrated Jewish holidays, Passover. The MJO-sponsored Passover Seder is usually a popular event on campus, often boasting over 200 attendees in the Kagin Ballroom.

MJO matriarch Gus Dexheimer ’20 assisted in adapting the annual seder to be held over Zoom at 7 p.m. on Wed. April 8. MJO let all of their members know that while the org wasn’t going to host the regular seder dinner, all members were invited to the virtual seder.

Dexheimer said that for her, personally, not having the regular seder dinner in her last year at Macalester is hard. Originally from Austin, Texas, she grew up hosting big seders in her backyard with her family, and over the years she has grown to love the MJO seder too.

“It’s hard to be in this in-between, where I’m not at home, but also not in my community here,” she said.

In an era where gatherings over ten are banned and leaving your house at all is frowned upon, MJO couldn’t host anything like a typical seder, which is a celebration of plenty.

“You gather dozens of people in your homes, you find whatever chairs you have, you squeeze them in,” Kippley-Ogman said. “People bring things — lots of food. [There’s] this sense of abundance and presence and a moment not just for the religious or ritual practice, but also for that recognition of family and of community.

“This year, it’s really the opposite of that,” she continued.

MJO leadership said they would do their best to provide the traditional foods that accompany seders to anyone who needed something for their seder at home. Dexheimer hopes that Jewish students recognize that the holiday has come amidst challenging circumstances.

“I think the biggest overarching thing is you’re only expected to do your best,” Dexheimer said. “That’s all you can be expected to do with Jewish practice and with any kind of practice, so I’m hoping it comes across as forgiving and flexible.”

“So if you don’t have leeks to hit people with on the computer camera, or boiled eggs, or matzo ball soup, I don’t think that matters,” Dexheimer said. “That is probably not why people come to it, or seek that kind of thing.”

Dexheimer also helped convert the weekly Shabbat services to take place over Zoom on Friday evenings. She acknowledges, however, that the celebrations are not quite the same.

“Probably my favorite part of Shabbat is cooking dinner… I love cooking a lot of food for a lot of people,” Dexheimer said. “I love when people start arriving and greeting people and seeing people, and it’s also hard to know how people are doing on Zoom and that I think Shabbat is good for [that].”

Both Dexheimer and Kippley-Ogman believe that MJO members will continue to participate in the weekly Jewish practices, either through engaging with the student org or with their families.

Muslim Students Association (MSA) is also keeping up with weekly meetings. They gather on Zoom on Fridays at 12 noon, their normal meeting time.

“Friday is the day where we come together and gather together and eat food together and pray together so we try to maintain that,” MSA member Mohamed Abdi Mohamed ’21 said.

MSA is currently deciding how it will celebrate the holy month of Ramadan. Under typical circumstances, the group usually meets every night in the kitchen in the CRSL and together they cook a meal together for iftar, to break the fast.

“So at night here at Macalester, we would come together and cook together, but now with everything going on… we’re going to have to figure out where we are going to get food from,” Mohamed said. “We will see how that works out.”

Stone worked with the Macalester administration to determine how to best accommodate MSA members.

“To lighten the burden of cooking and meal preparation (which is often done in community) approximately 1/3 of the 30 days, meals will be available via curbside pickup at local restaurants, for local students,” Stone wrote in an email to The Mac Weekly. “Paired with regular digital gatherings to break-fast together, we are hopeful that we can preserve an important communal experience of Ramadan.”

Mohamed is a little concerned for Muslim students who are still living on campus, trying to celebrate Ramadan away from their families and virtually with MSA.

“They won’t be back home, but then they won’t be with us as well,” Mohamed said. “Before it was like ‘Yeah, even if you’re not going back home, you have a community that supports you, you come together, you hang out together, you eat together, you cook together, so it feels like home.’ I think that might be hard for some students.”

MSA is also grappling with a lack of a Muslim chaplain currently. Former Muslim chaplain Ailya Vajid departed Macalester in August 2019, and now serves as the Muslim chaplain at the University of Virginia.

Mohamed said the absence of a chaplain has pushed the upperclassmen to reach out and connect with the Muslim first-years so they know that they have a home.

“For the Muslim students who are first-years, if there is a Muslim chaplain, it’s easier for them to approach the chaplain, because they know that the person is there for [them], and the connection becomes easier and you have a lot to talk about,” Mohamed said. “Kelly [Stone] has been trying to connect us to first-years and prospective first-years.”

The search for the new Muslim chaplain, which began last semester, is now on hold in light of the ongoing pandemic.

“Right now, we’re in a bit of a pause because doing interviewing with candidates is actually quite complicated and the college is taking prudent financial steps to ensure the well-being of all members of our community in this moment,” Stone said.

For now, Stone has been attending the weekly MSA meetings and coordinating preparations for Ramadan.

Meanwhile, Macalester Christian Fellowship (MCF) have also been maintaining their regular meeting schedule on Zoom. While MCF didn’t plan a virtual Easter celebration, Macalester-Plymouth Church made a stream of their Holy Thursday, Good Friday and Easter Sunday services available to the Macalester community.

MCF member Jennifer DeJong ’21 attended her home church’s virtual Easter Sunday. She just got back to Minnesota from an abbreviated semester abroad in Edinburgh. She’s been taking the opportunity to get back in touch with her community back in Sammamish, Wa.

DeJong, who stepped back from MCF leadership to go abroad, has been attending the org’s weekly meetings on Zoom. While she appreciates the time to catch up with her friends, virtual meetings haven’t fostered the same spiritual reflection as those that took place in the oasis of the CRSL.

“One of the nice things is in that central area when there’s no one around it does feel isolated from the rest of campus, which I think can lend itself to more vulnerability in discussion,” DeJong said.

It’s the loss of these safe spaces that led Queer Faith Community (QFC) facilitators Amelia Gerrard ’20 and Jessi-Alex Brandon ’20 to call off meetings for the rest of the semester.

One of the founding tenets of QFC is anonymity. The group prioritizes creating a space where individuals can openly discuss their identities without fear of judgement. While private Zoom codes and password-protected meetings may sound like a safe option, there are still dangers.

Now, many students have moved back into homes that may not be accepting of their queer and or trans identities, and attending Zoom QFC meetings is no longer an option.

Besides, Gerrard said, having that space — that physical environment fostering community — was always essential to the QFC experience.

“There’s an ability to say things to everyone in the Queer Faith Community space that you wouldn’t be able to say otherwise just because you know you’re protected physically and emotionally,” Gerrard said. “By losing that space, I think we lose a lot of that progress that we make.”

Gerrard founded QFC back in her sophomore year, and has facilitated the group ever since. Having to finish out her senior year remotely and without this part of her identity and support network has been challenging.

“To have it end so suddenly is really heartbreaking because… I don’t get to say goodbye to all these people that are really important to me,” Gerrard said. “And then also, it’s just such an anticlimactic end to all of the work that I’ve done and all of the work that my counterpart Jessi-Alex has done.”

However, while QFC is no longer meeting, Gerrard has stayed active in Westminster Presbyterian Church in Minneapolis, where she is a Youth and Family intern. She also attended a virtual candlelight service at the conservative Episcopal church she grew up in. It’s something she hasn’t done in the years since she came to Macalester.

With her internship, her personal practice and her capstone on female divinity, faith has been occupying her mind a lot lately.

“A lot of Christianity is based on this experience of powerlessness,” Gerrard said. “We are practicing a faith where we have a belief in something greater than ourselves aiding us and helping us and I think COVID-19 is the ultimate form of being powerless.”

For the most part, faith communities at Macalester have rallied together in this time to find strength.

“That’s how you sustain yourself in times like this — is to reach for the practices that will hold you and that will challenge you to be helpful in the world,” Kippley-Ogman said. “That’s what I’m seeing.

“People are trying to show up with all the skills they have,” she continued. “To me, those are the core practices of a powerful faith.”