The history of this land

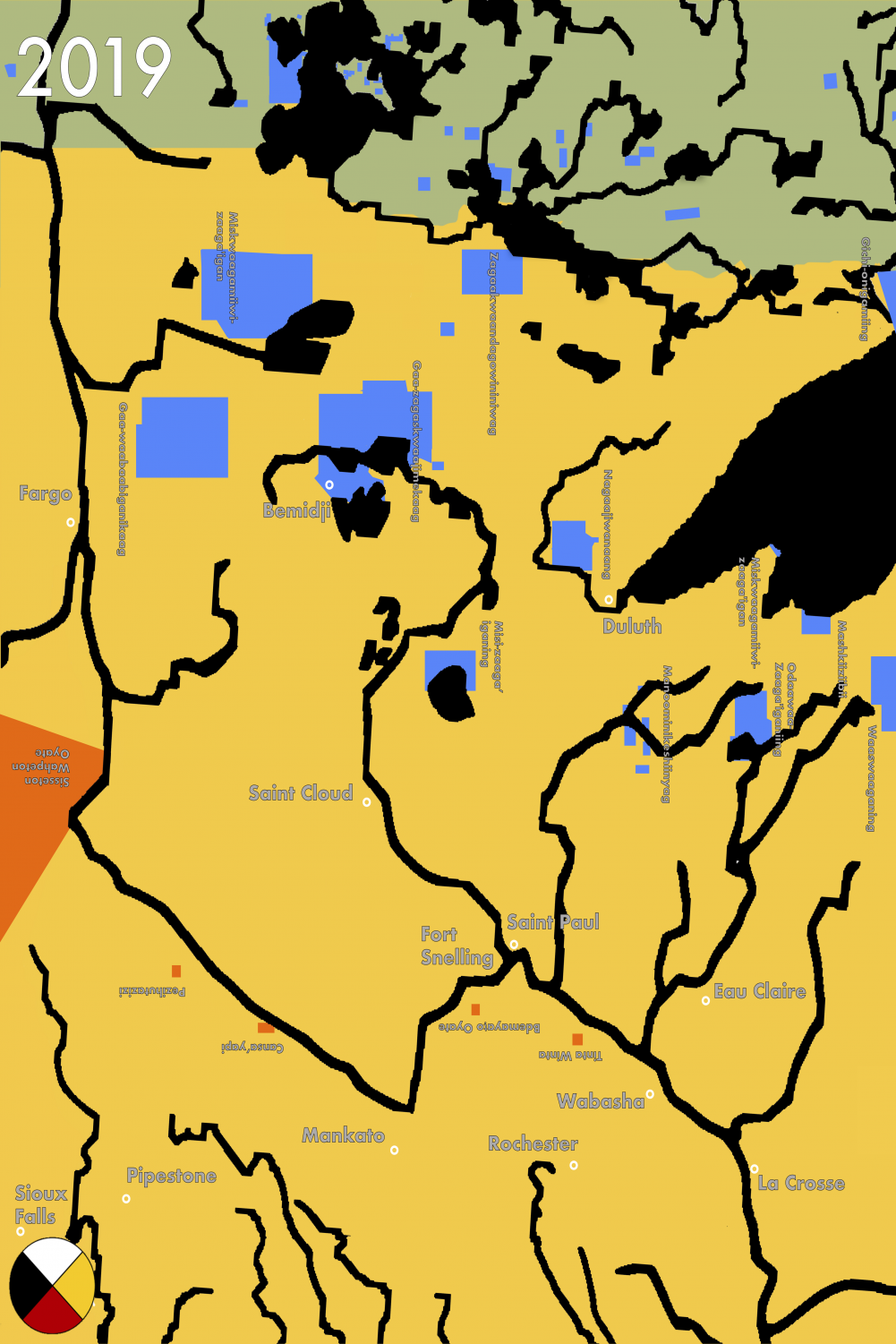

The Dakota, Anishinaabe and U.S. all use different navigational conventions, which are reflected in the maps. For the Dakota, south is up, while it is east for the Anishinaabe. The U.S., like many other colonial entities, uses north as up. Mergenthal displayed all eight of their maps, several are pictured on this and the proceeding page, on tables so that they do not have a “true” up. They did not have time researching their IRT presentation to find out about Ho-Chunk navigational conventions, so oriented them to the west, the lone remaining direction. Maps courtesy of Jennings Mergenthal ’21.

October 31, 2019

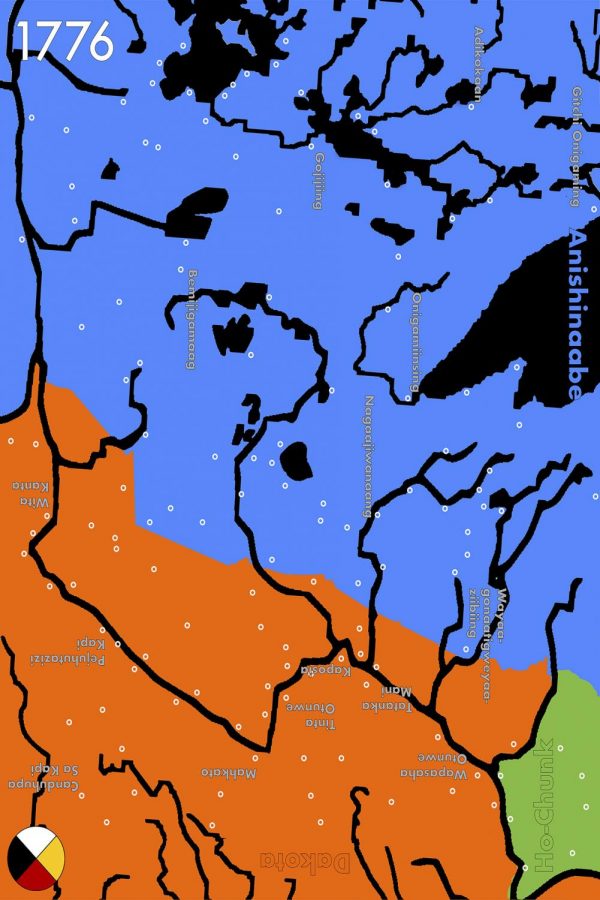

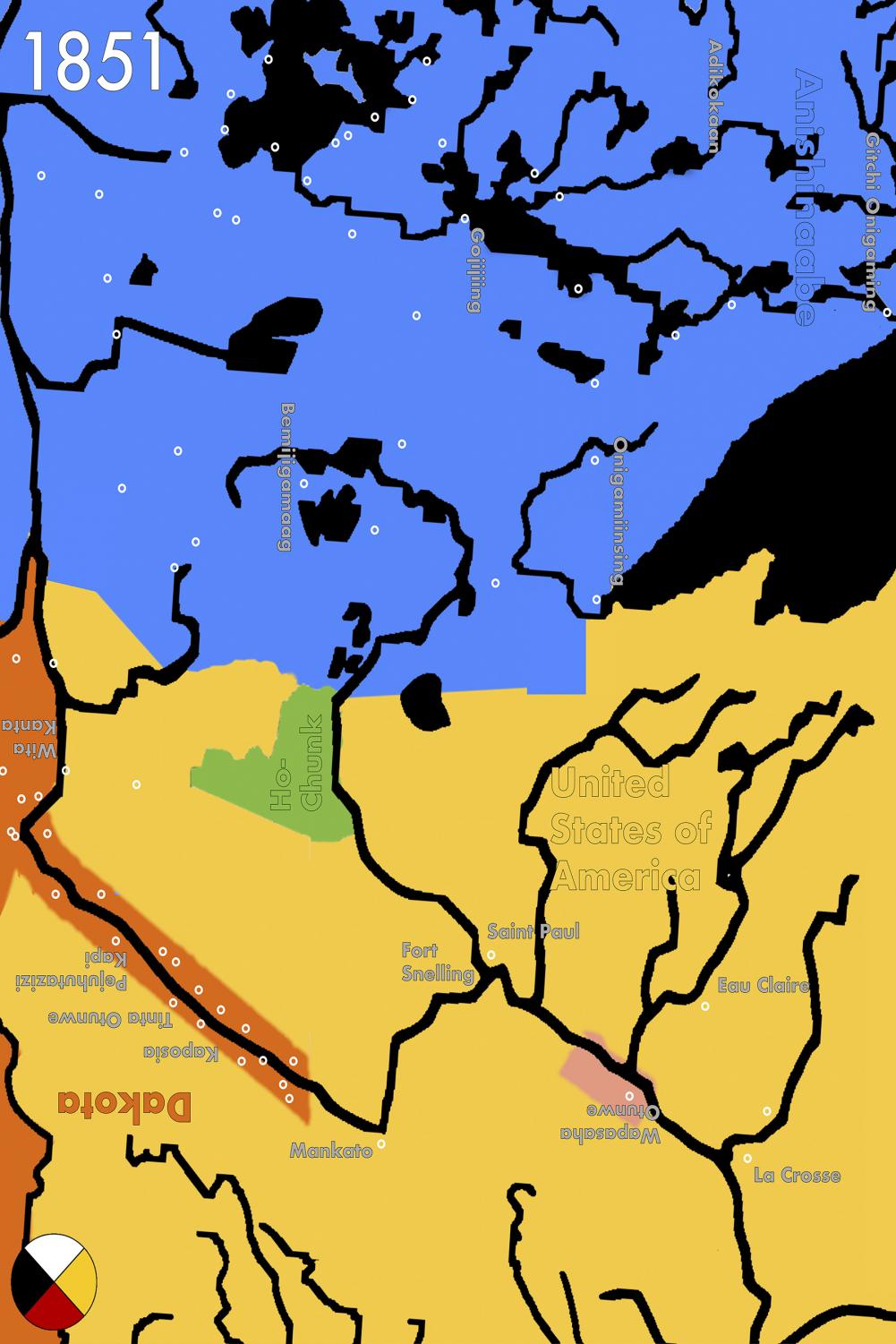

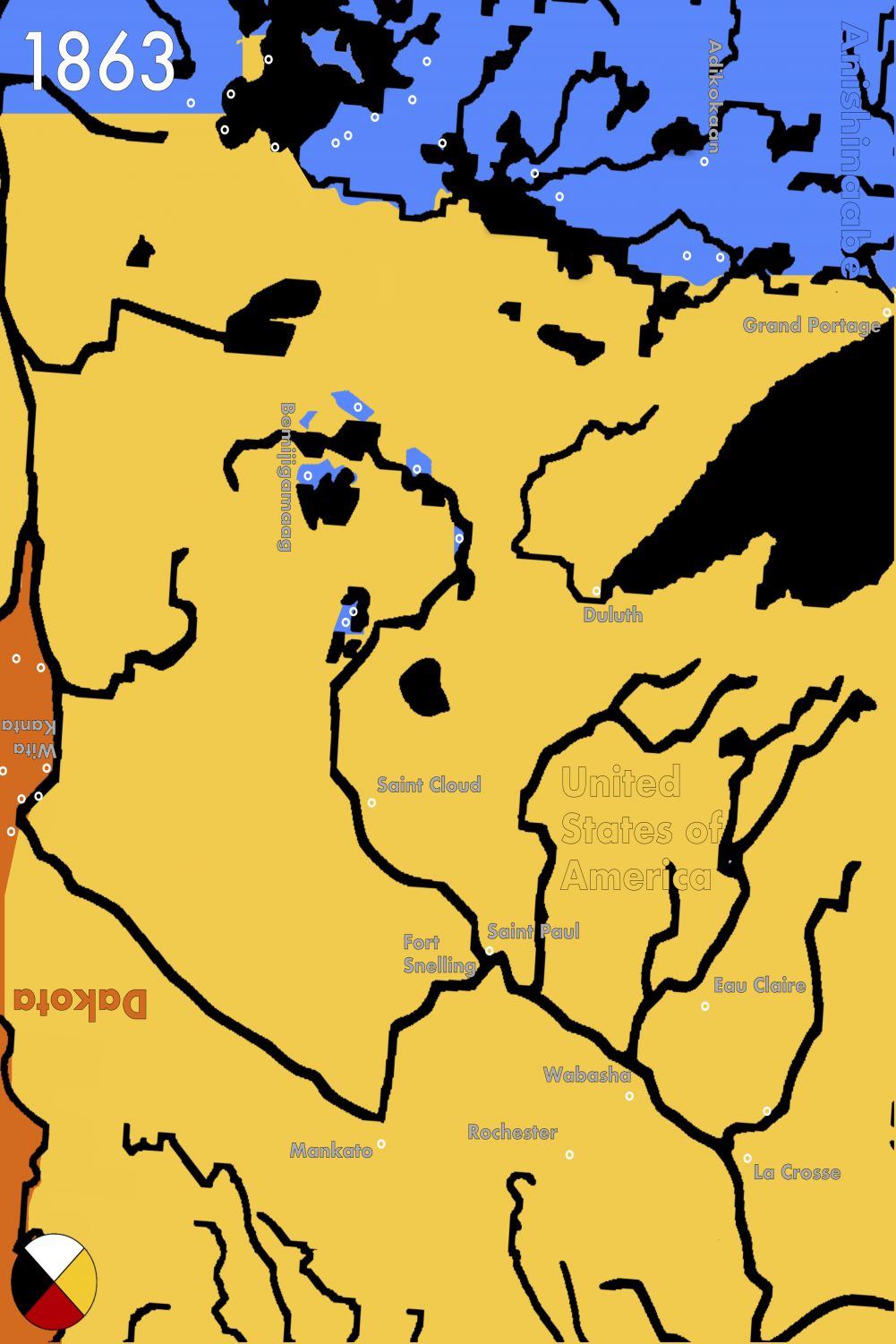

At this year’s International Roundtable (IRT), Proud Indigenous People for Education (PIPE) co-chair Jennings Mergenthal ’21 presented a sequence of maps detailing the history of the land of what is today Minnesota and the surrounding area.

Mergenthal’s maps range from 1776 through 2019, illustrating where the Anishinaabe, Dakota and Ho-Chunk peoples lived and when they lived there.

The maps were installed in the Weyerhaeuser Memorial Chapel on Thursday, Oct. 10 and Friday, Oct. 11 of IRT alongside a number of primary sources and interpretive signage, presenting a decolonized history.

“Even the better versions of maps that show indigenous land hold pre-colonization… the state or national borders are still superimposed over the maps, which casts the formation of the states as an inevitability — which it wasn’t,” Mergenthal said.

Presenting the formation of the states erases 10,000 years of indigenous existence in North America.

The earliest map in Mergenthal’s installation depicts the land holdings of Anishinaabe, Dakota and Ho-Chunk people. The United States of America does not appear on the map.

The United States government did not have a formal presence in what is today Minnesota until 1805. Over the following six decades, the United States stole the rest of modern-day Minnesota through a pattern of aggressive and persistent settler-colonization.

That included negotiating and then breaking treaties with sovereign, indigenous nations, like the Dakota, Anishinaabe and Ho-Chunk.

Mergenthal’s maps — from 1776, 1805, 1837, 1847, 1851, 1858, 1863, 2019 respectively — detail the shift in land holdings during that period.

The 1851 map reflects the forced displacement of Dakota people caused by the Treaties of Mendota and Traverse des Sioux. Those treaties were negotiated by then-territorial governor Alexander Ramsey, and federal commissioner of Indian Affairs Luke Lea.

Through those treaties, the United States government forced the Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands to cede 21 million acres of land, while the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Bands ceded 14 million acres.

Shortly after this cession of lands, a number of colleges and universities — including the University of Minnesota, Hamline University and Macalester College — were founded on the stolen land.

“The reason all of these institutions could be founded when they were is because of cessions of Indian land,” history professor Katrina Phillips, an enrolled member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, said. “That’s not an indictment of Macalester. Nobody who is at Macalester today is directly responsible for any of this. But if we’re going to talk about the history of Macalester College, we can’t start in 1874.”

The history of the land Macalester occupies goes back thousands of years.

Evidence of millennia of indigenous existence appears on land occupied by Macalester College at the 300-acre Ordway Field Station in Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota. The Field Station, on the bluffs of the Mississippi River, is used for ecological education and research across several Macalester departments.

“Ordway presents very plainly, and with material evidence, the fact that Macalester is on Native land,” Abby Thomsen ’20 said. “Not that we need material evidence for that, but it shows that Macalester owns land that has been inhabited for over 2,000 years.”

Thomsen became involved with the Ordway site while taking an archaeology class taught by anthropology professor Scott Legge. She is now doing an honors project to add interpretive signage to the Ordway property.

Legge’s class conducted a cultural resource survey of Ordway, which revealed four archaeological sites that predate contact between indigenous peoples and European colonists.

He taught the same class in 2018 near Ordway at the Pine Bend Bluffs Scientific and Natural Area, and Thomsen worked as his assistant in a literature review and partial excavation of the site. Directly across the Mississippi River from Pine Bend is Gray Cloud Island, where a Dakota village led by Chief Waukan Ojanjan, also called Medicine Bottle, existed in the 1820s.

The village inhabitants were forced to leave Gray Cloud Island in 1837 after the Dakota ceded land to the United States in a treaty and moved near Pine Bend, close to the Ordway property.

“We know [the village] was in that general area,” Thomsen said. “We don’t need to know exactly where it was to realize that it is part of that greater landscape and connect it to the U.S.-Dakota War, treaty-making, westward expansion and genocide.”

Waukan Ojanjan’s nephew, Wakan Ozanzan, also called Medicine Bottle, exemplifies these concrete connections. He famously fought in the U.S.-Dakota War, and after it ended, eluded capture by the U.S. and escaped to Manitoba alongside another famous Dakota leader named Sakpedan, also known as Shakopee.

In 1864, the two were drugged and captured north of the U.S. and handed over to the U.S. Army. They were publicly executed at Fort Snelling on Nov. 11, 1865.

But those deaths are far from the only connection between Macalester College and the U.S.-Dakota War.

After arriving in Minnesota in 1849, Neill became friends with some of the most prominent and important settler colonists in Minnesota — including future governors William R. Marshall, Alexander Ramsey and Henry Sibley, the architects of the U.S.-Dakota War.

Ramsey and Marshall were founding members of the board of trustees at the Baldwin School, the prep-school precursor to Macalester College. According to Dr. Jeanne Halgren Kilde’s “Nature and Revelation: A History of Macalester College,” Sibley was an “early supporter” of the college.

In 1863, shortly after the war’s end, Congress passed the Dakota Removal Act — making it illegal for any Dakota to live in Minnesota. In the years following the Act, the violence of white settler-colonization did not end, nor did the influence of men connected to Macalester.

In an 1868 letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs Hon. N.G. Taylor, Neill argued for stricter policies to civilize indigenous peoples, including forcing indigenous peoples to wear western clothing in the presence of Indian Agents. Another of his suggestions, known as allotment, became law in 1887.

The General Allotment Act of 1887 divided indigenous reservation land from communal into individually owned plots. It also opened the door for the U.S. government to steal more land for white settlers and corporations. According to the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, from 1887 to 1934, indigenous land holdings decreased from 138 million to 48 million acres across the United States.

That attack on indigenous sovereignty was part of a broader program of forced assimilation. In 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School opened its doors in Carlisle, Pennsylvania with U.S. governmental authority. Its mission, according to founder Lt. Col. Richard Henry Pratt, was to “kill the Indian, save the man.”

Over the following decades, boarding schools became government policy to force assimilation. The United States Bureau of Indian Affairs operated 26 similar boarding schools where students were forced to cut their hair, use English names and were forbidden from speaking their native languages.

Those schools forcibly educated tens of thousands of indigenous children.

The United States did not grant indigenous people citizenship until 1925, and even that action was designed to demean their sovereignty.

During IRT, Mergenthal displayed a map from 2019 that illustrates both that indigenous peoples still exist and that the impact of settler-colonization is not merely historical.

In an interview with The Mac Weekly, Mergenthal explained the need to reframe colonial histories not as something that happened, but rather as part of an ongoing process.

“The notion of a history itself serves a purpose in a colonial context as opposed to, say, situating it as an eternal present, where these are things that have happened, but still continue to happen,” Mergenthal said.

“So if you look at state violence against the Dakota not as a ‘that is then and this is now and here are the parallels,’ but as a ‘here is a[n] ongoing arc of the present that is a continuation of the same beliefs, policies and legacies,’” they continued. “It’s a way of framing it that’s implicitly far more critical to the settler.”

In his new book, “Translated Nation: Rewriting the Dakhóta Oyáte,” English and American Indian studies professor at the University of Minnesota and enrolled member of the Spirit Lake Nation Christopher Pexa connected that arc to the #NoDAPL protests of 2016.

Pexa argued that the protest camp at Standing Rock — which unified the Oyáte, or People of the Seven Council Fires, an allied confederation of Dakota/Lakota/Nakota people including the Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands — constituted an actively decolonized space.

That the decolonized space was used to resist the U.S. government and achieved widespread support and awareness, was what prompted the government to respond “with radically increased surveillance, militarized police force, and violence,” Pexa wrote.

While the context was different, the state violence inflicted by the U.S. against water protectors resisting the pipeline’s construction is a continuation of the same arc that extends back hundreds of years.

PIPE co-chair Zoe Allen ’22, an enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, also connected the historic pattern to the impact of the ongoing displacement of indigenous peoples.

“When we’re talking about indigenous issues, we cannot only focus on pipelines and renaming buildings,” she said. “We have to also think about police brutality, missing and murdered indigenous women, the opioid epidemic.”

According to 2015 data from the Center for Disease Control (CDC), indigenous peoples are killed by police at a higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States. Indigenous peoples also had the highest drug overdose rates of any racial or ethnic group in the country.

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) crisis is another of the many issues that profoundly affects indigenous communities and is largely ignored by white Americans.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, indigenous women on certain reservations are “murdered at a rate more than 10 times the national average.” A 2012 report from the Department of Justice also found that 46 percent of indigenous women have experienced “rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner.”

The Center for Disease Control, meanwhile, found that homicide is the third-leading cause of death for 10-24 year-old indigenous women and the fifth-leading cause of death for 25-34 year-old indigenous women in the United States.

The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women pinpoints the issues caused by a lack of communication — and jurisdictional differences — between federal, state, local and tribal governments as one of the key reasons for the ongoing “pattern of structural violence” against indigenous women.

In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe that tribal courts do not have jurisdiction over non-indigenous people — a decision that, according to the National Institute of Justice, “essentially provided immunity to non-Indian offenders and compromised the safety of American Indian and Alaska Native women and men.”

This problem is compounded by the very thing that the water protectors at Standing Rock were protesting: the construction of pipelines that extract resources from indigenous communities.

According to an article published in The New Republic on Oct. 15, “Pipelines, a growing body of research suggests, can actually fuel violence against Native women.”

Where pipelines are constructed, energy companies create temporary housing communities for their workers known as man camps. A 2012 study in the Western Criminology Review found an 18.5% increase in violent crime in oil- and natural gas-producing counties in Montana and North Dakota. A key aspect of the increase in violent crime connected with the man camps is an increase in sexual violence, much of which is directed at indigenous women.

This kind of violence has been particularly destructive in the Tar Sands region of Alberta, Canada, and the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota and Montana.

That the Bakken fields in North Dakota have been so dangerous for indigenous women and girls is no coincidence, given that North Dakota has enacted legislation that renders indigenous people lesser citizens than others.

In 2017, the state passed a voter identification law requiring that voters have an ID that includes a “residential street address.” Many indigenous people in North Dakota live on rural reservations, which don’t have street addresses, and are therefore barred from voting.

A district court blocked the implementation of the residential street address portion of the law after a lawsuit, but an appeals court halted the district court order.

After a series of court battles, the Native American Rights Fund appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, but, less than a month before the 2018 midterm election, the Supreme Court denied their request and the law went into effect.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, the law disenfranchised as many as 70,000 people in North Dakota in 2018. That year, in an intensely competitive U.S. Senate race, incumbent Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) lost to now-Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-ND) by a fraction over 35,000 votes.

The process of white, settler-colonization that Edward Neill and Macalester College by extension participated in is ongoing. Its enduring impact affects much more than a building.

This article is part of the Mac Weekly’s special reporting project, Colonial Macalester. Read the entire issue here.