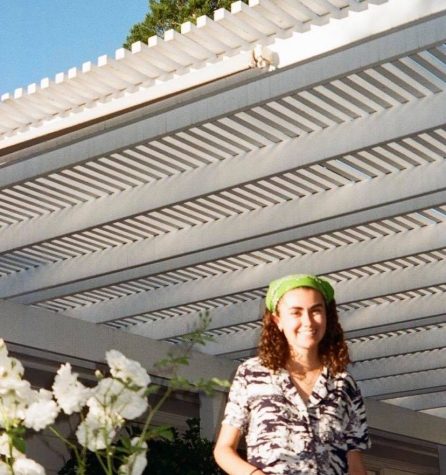

Macalester alum speaks on art, research and resistance

September 19, 2019

Last Wednesday, Macalester alum Heba Y. Amin ’02 came back to campus for the first time since she graduated. Since her time as a student, she has made waves with her performance art and research. Most famously, Amin took part in the graffiti work done on the set of the TV series “Homeland.” With two other artists, Amin critiqued the show itself with subversive language. The episodes aired months later causing the show to unknowingly criticize itself. After the story broke, it went viral and was reported by media all over the world.

Her talk, entitled “Female Subjectivities & Technological Dystopias,” began with an examination of photographs taken on the African continent in the 18th and 19th centuries. The images, Amin argued, highlight how Europeans portrayed romance and sexual fantasies in their constructions of geography and women. For example, in many of the sketches, the African landscape serves as the background with a naked, sexualized woman in the foreground.

Women became colonized like the settlers “claim[ed] the land,” Amin said. “The body of the woman is equated with the mapping of geography. The idea of the woman is implied through voyeuristic gaze.”

The Europeans romanticized both women and the land and turned them into “propaganda of sexual desire,” Amin said. Colonizers “imagined [the soon to be conquered land and women] becomes the neurotic image.”

This investigation brought Amin to the conclusion that art and media have the capacity to normalize misconceptions. In 2014, she embarked on a mission to unveil the similar dynamic of media fetishizing immigration crises happening all over the world.

“I wanted to critique the media’s ‘refugee porn’ kind of narrative,” Amin said.

She traveled from Lagos to Berlin along contemporary migration routes to try to understand the experiences migrants face. Amin herself called the project “problematic” because of the privilege she has in contrast to the rights and abilities of migrants.

“Where does that put me as an artist in retelling this narrative?” Amin said. The journey was taxing and expensive. Amin had to apply for 14 visas without a clear idea of what kind of art she would end up with.

In preparation for her trip, Amin researched the geography and history of the land, most of which she found was documented by colonizers with romanticized and racist descriptions. The reality of mapping and photography is an inherently intimate and controversial conundrum, Amin found through her research. The first comprehensive text describing West Africa under the Islamic empire — compiled by historian and geographer Al-Bakri in the 11th century — was an anthology of firsthand accounts of geography. Amin found that through these accounts of geography the respondents associated women’s bodies with sexuality, novelty and land, much like the sketches of Africa. With this realization, Amin decided to retrace the steps of different photographers and artistic endeavors along migrant routes.

In order to properly replicate geographers’ historical actions, Amin used an old kind of camera; a theodolite. Theodolites have the capacity to zoom incredibly far with a telescopic lens. With this piece of equipment, which was a predecessor to military technology, Amin was struck by the invasive ability to create a public narrative off of people’s lives — similar to how the media features the intimate stories of displaced people. “It felt like I was setting myself up to shoot somebody,” Amin said on using the theodolite, as it has cross hairs in the lens. This powerful and potentially violent act of preserving history is what Amin has shifted the focus of her work towards.

One way in which history and its study has remained narrow is through the actions of dictators, who created distractions and reshaped history. To combat this, Amin performed the aesthetics of fascist movements with photographs and recreations. Pulling language from famous dictators, their speaking tendencies, physical attributes and even their flower arrangements, Amin staged a speech in Malta in 2018 where she attempted to convince an audience that she was going to drain the Mediterrean Sea — something many geographers (and even the CIA) had advocated for up until the 1950s.

The performance was advertised to the Maltese people as authentic, and Amin held a question and answer portion at the end. She found that turning herself into a megalomaniac and studying megalomania was a kind of research that she never thought she might undertake. But, as is the case with most performance art, according to Amin, “you’re understanding [the art] as you’re putting it out into the public.”

Amin’s work is located at the convergence of academia and art — two professions that overlap but have very different resources and execution. Amin spoke about her privilege in this way as she can access academic archives and also gain fame and funding as a public artist. She enjoys putting these tools against each other and sees this as necessary while the media becomes increasingly problematic and lacks legitimacy. Amin believes that artists and academics fill these gaps, when journalists can’t be as outwardly critical. It is clear that Amin will continue to do work that will push the boundaries of research, academia and resistance.

Amin currently serves as a professor at Bard College in Berlin, is a doctorate fellow in art history at Freie Universität and is a current Field of Vision fellow in New York City. To learn more about Amin and her current exhibition at the Minnesota Museum of Art, visit www.hebaamin.com/.