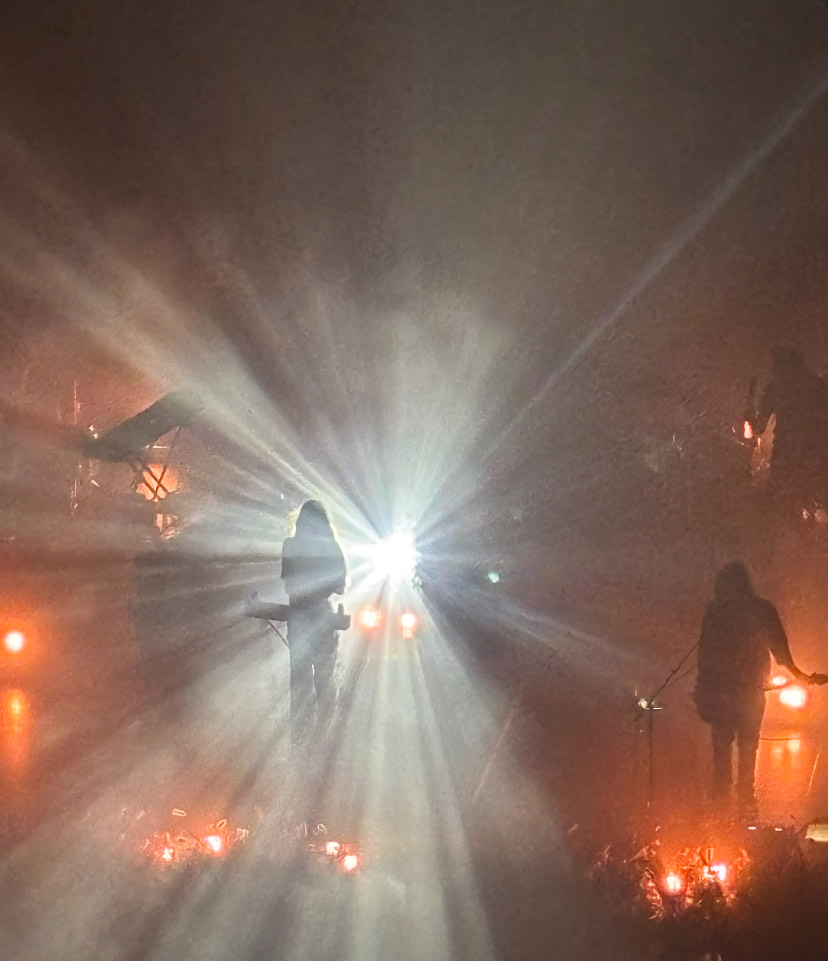

Lady in Purple, played by Nana C E Adubea Toa-Kwapong ’16, is the first to enter the chapel. She dances down one of its aisles with a cream-colored cloth. The song is “So Beautiful” by Asa. All in black, with a purple headwrap, she moves the cloth in luscious circles, controlling it like it’s water in the air and captivating the people in the pews. The benches are mostly occupied, though there is space between people.

Toa-Kwapong reaches the center of the chapel. A pile of pillows waits there in a warm pool of light on the hardwood. Her cast members slowly enter and arrange themselves, reclining amongst the pillows. Some lie down. One performer rests their head on another’s shoulder.

For colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf was performed in the Weyerhaeuser Memorial Chapel last Friday and Saturday by a cast of eight Macalester students. The production was directed by Harry Waters Jr. and sponsored by the Black Liberation Affairs Committee (BLAC). For folks that missed it: the words of each performer swirled and swelled in the chapel like a storm. It felt at times like riotous joy and other times like gut-wrenching pain.

Bringing the rainbow to Macalester

This “choreopoem,” a term coined by the work’s creator, Ntozake Shange, first saw the lights of Broadway on Sept. 15th, 1976. It’s a collection of 20 poems, intended to be accompanied by music and dancing. The language in the text dates back to the 50s, 60s and 70s, referencing people like Willie Colon and something called “El Son.” Each woman is identified only by the color of the scarf wrapped around her head (Lady in Coral, Lady in Red, etc).

For colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf first appeared at Macalester 12 years ago: Kyla Martin ’15, co-chair of BLAC and organizer of the production, noticed a photo of the cast on the desk of a faculty member. After this, it all began to fall into place. Waters approached her about putting on the show.

The eight women had some help from Laurie Carlos, one of the original cast members in the Broadway production. Waters connected the critically-acclaimed professional with the students, and Carlos worked with them during their first rehearsal back in December. The students would pick up the work again in February, and in all but a month memorize monologues, perfect songs and choreograph dance. Some cast members had never before participated in a theater production, although their professionalism onstage made that hard to believe.

The group rehearsed about four times a week, warming up together, checking in together and then going through the piece. Each actress met with Waters once or twice during the month leading up to the show, for one-on-one time with the different poems.

They didn’t actually perform the show in the space until the Monday before opening night.

“The turnout was just as powerful as the actual show,” Toa-Kwapong says, explaining the significance of that first night acting in front of an audience. “That was the highlight of the process.”

“Living in the world”

Not long after they entered the chapel, the performers removed their scarves from their heads and tied them in different fashions — around waists, over shoulders, around necks. Each actress in her own style, her own expression, her own experience. And each actress would have a pivotal moment in the poetry she performed.

“I used to live in the world! Then I moved to Macalester,” Becky Githinji ’18, Lady in Teal, said at the end of a poem called “Harlem.” The word “Macalester” is a shock: we’re expecting to hear the word “Harlem” again at the end of this recurring line. There are snaps and emphatic “oooo!”s in response. Much of the audience seemed to relate all too well to the difficulty that many students have, particularly students of color, in adjusting to Macalester. A simple change in the script made Githinji’s words instantly relevant to our community — a community with a lot of work still to do.

“Somebody almost walked off with all of my stuff!” Gabriella Gillespie ’17, Lady in Fuschia, screamed. She yelled and cursed at the audience in another powerful poem, expressing her deep frustration with the devaluation of her life, and black women’s lives, in general, by talking about a man taking her “stuff” (her smile, her laugh, her kiss).

Earlier in the play, Gillespie delivers a hilarious monologue as an eight-year-old fantasizing about the great Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, only to find a much less romantic, but English speaking, Toussaint Jones instead.

Interspersed with darker, more jarring moments are instances of laugh-out-loud humor. Marie Johnson ’17, playing Lady in Black, incited uproarious laughter with her deadpan, matter-of-fact delivery of several one-liners.

At one point, the women actually play in a parachute — the big, technicolor, elementary school kind — laughing and running like little kids. Eventually they grow still and the parachute is laid down. Lady in Coral, Megan Britt ’15, walked through it. She lets a red cloth fall from her hands, symbolizing the blood of a rape. Her face is cracked apart by the pain she embodies in that moment.

In this way, the choreopoem works much like life, with the beauty mashed right up against the pain. The performers had the maturity and grace to let the gravity of harder moments sink in. But they never let the momentum of the story fall. A performer picked up the thread of the work just as another let it go, almost like they were healing each other when moments got too difficult to bear alone. They cycled through the poems seamlessly, holding each other up and keeping each other safe.

It feels almost prayer-like when Maritza Steele ’17, Lady in Blue, laid out a long blue cloth across the center of the chapel. In a soothing, tender voice she told a story about a woman crying herself to sleep every night. Another haunting moment comes when Niara Williams ’18 (Lady in Red) and Githinji sing together, entering the chapel from opposite sides and slowly passing each other in the middle. Their pure, clear harmonies cut through the weighty silence of the chapel.

These poems could be written off as fiction. Except they’re not. Near the end of the play, Martin delivered perhaps the most disturbing poem, which concludes with a father dropping two of his children out of a five-story window. Actress and organizer Martin said the playwright, Shange, saw this happen.

VIPs

After the Saturday night show, when the lights came up and performers had taken their final bows, Harry Waters Jr. jogged to the center of the chapel to announce the presence of a few very special guests.

He invited them onstage — about a dozen girls, ages 10 to 17, immaculately manicured in long flowing gowns and party dresses.

They came from Brittany’s Place, a shelter in Minneapolis for girls who have experienced sexual exploitation, abuse or trafficking. Martin had the idea to bring the girls to a show: she collected dresses for them, and during the day on Saturday, the cast of the show and the girls got ready together. Hair, make-up, nails. The girls didn’t realize that they got to keep the dresses.

“They were really quiet at first,” Martin explains. “We didn’t want to over-engage; we wanted to find that balance.”

Martin says she doesn’t like calling it a service project because it didn’t feel like one. It was just fun.

“I think it also grounds the work,” she explains. “Abuse happens in the community you’re in.”

Finding Rainbows

“Life is not without pain,” Steele said. “Something that was so inspiring about the people that I worked with was their ability, for even a moment, to overcome fear and share in something great.”

All of the performers had to embrace vulnerability. And all of them had to find a certain power in that vulnerability in order to tell these stories.

“Part of me was in that poem,” Martin said, reflecting on her last lines about a mother losing her babies. “Realizing that I had the power to say it was a big thing.”

A feeling of indomitable sisterhood emanated from the group, whenever they were together. Especially in the last moments of the production when they all stood together, legs apart, arms outstretched towards the ceiling.

“And this is for colored girls who have considered suicide, but are now moving to the ends of their own rainbows,“ they proclaimed in unison. The lights went out, and the people in the pews sprang to their feet.

Sarah Lambert • Sep 9, 2019 at 4:23 am

Hello, I read your new stuff daily. Your humoristic style is awesome, keep it up!