“Twilight” and the double standard for teenage girls in YA

March 24, 2022

Content warning: this article contains mentions of sexual assault and spoilers for plotlines.

In 2008, fans of the book saga “Twilight” by Stephenie Meyer lined up outside theaters to see the first book turned into a film on the big screen. The major demographic in these crowds for the now worldwide franchise was teenage girls, most of whom featured on-theme T-shirts with the iconic movie poster printed across the fronts.

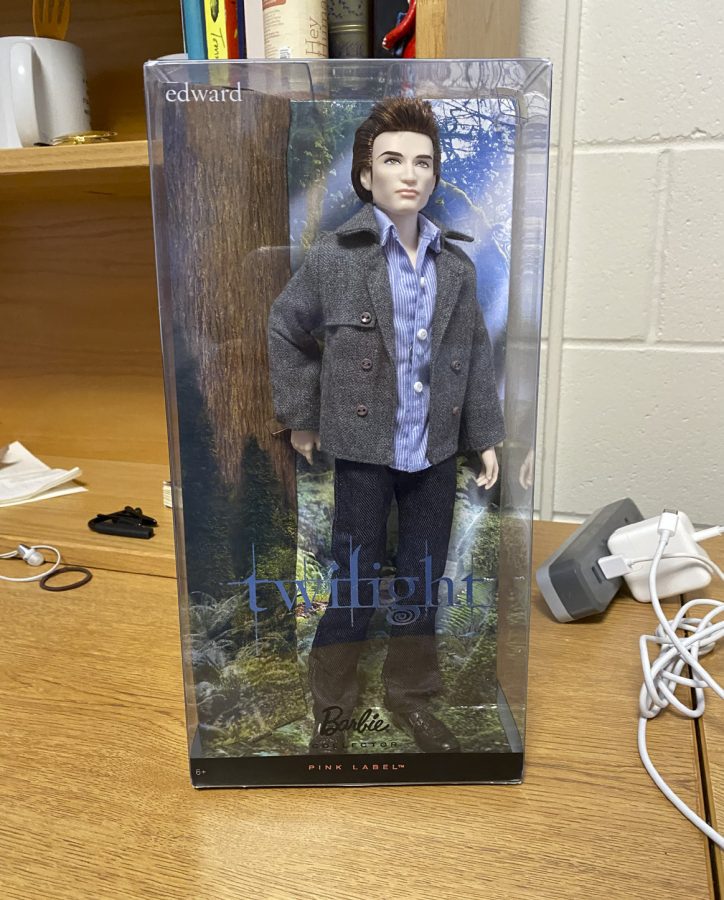

Since then, “Twilight” has become a peculiar case study: it has a wildly successful, dominating cultural phenomenon — a story about Bella Swan, a human, who falls in love with Edward Cullen, a vampire, and the supernatural teenage drama that ensues. Yet at the same time, “Twilight” is one of the most ridiculed works of fiction in recent history. At one point, it was considered cool to hate it — even Robert Pattinson, who starred as Edward, seemed to despise the story.

What it comes down to is that the world loves to hate what teenage girls love, simply because teenage girls love it.

The narrative that surrounds “Twilight” and other similar aspects of culture and media targeted toward teenage girls goes beyond the idea that “Twilight” is unintelligent and instead says that not only is it unintelligent, but if you like it, you are also unintelligent. “Twilight” was never seen as just a guilty pleasure that a lot of people have; rather, it was used as proof of teenage girls’ intellectual inadequacy.

Still, most would agree that Stephenie Meyer is one of the defining authors of the current Young Adult (YA) genre, a genre that itself is mostly written for teenage girls and is consequently often not thought of as containing “real” books. Instead, a well-known YA title like “Twilight” makes many people who consider themselves intelligent members of society roll their eyes. Of course, vampires and forbidden coming-of-age romances are indeed tropes that we’ve seen again and again in the past twenty years. However, in 2005 when Meyer published “Twilight,” her Edward and Bella love story was the first of its kind — this vampire trope became cliche because of Meyer’s fiction, not in spite of it. She paved the way for authors who rode the wave of her success when they saw how popular “Twilight” was, but her ideas have always been completely her own, for better or worse.

So if we put aside the cliche argument and accept that Meyer was successful enough she created an entire sub-genre of YA, there are other potential reasons for disliking the story. Some may think, perhaps subconsciously, that they have a sort of literary authority over teenage girls that gives them the license to belittle “Twilight” and others things like it. Many of these critiques are not given in equal measure to teenage boys.

Whether a teenage girl’s perspective is respected or not, there is one argument against “Twilight” specifically that does have textual evidence: the saga has a lot of issues that could leave its readers with problematic conceptualizations about the world and relationships. One of the most well-known issues is the toxicity and incredible dependency of Bella and Edward’s romance; after all, it starts with Edward peering through Bella’s window and watching her sleep. Bella is honored to be his object of affection (by affection, I mean stalking), and this likely comes from her feeling of complete unworthiness of Edward that she mentions at least twice a chapter for the following four books. It gives their relationship a quality of subservience that leads to Bella’s extreme depression when Edward leaves her and later, his “Romeo and Juliet” decision to kill himself in “New Moon,” although he doesn’t end up dying. Defining love as this roller coaster of toxicity does not give young girls a good example of a healthy relationship.

And the problems with “Twilight” do not stop at the romance. In the third book of the saga, Jasper Hale, one of Edward’s adopted vampire siblings, tells the story of his experience as a Confederate soldier with fond memories and pride. No one questions this, not even Bella in her internal monologues.

In that same book, Jacob Black, the werewolf best friend, sexually assults Bella twice. The first time, he kisses her without her consent and she punches and then forgives him. The second time, he threatens to get himself killed in a vampire-werewolf battle if she doesn’t kiss him, and after Bella does kiss him, Meyer ends the scene with Jacob being described as a hero.

In “Breaking Dawn,” members of the Cullen family are suspiciously pro-life, saving the life of Bella’s half-vampire baby even as it is killing her. Also in that book, Jacob — the manipulative sexual assaulter — “imprints” on Bella’s daughter once she is born, and while this is described as a werewolf connection where Jacob won’t feel romantic feelings for the child until she is of age, the entire concept is rather close to grooming.

Now, fans of “Twilight” acknowledge these flaws in all their complexity; they make fun of these crazy, problematic scenes and ensure that Meyer understands where she went wrong. Still, fans love “Twilight” for all its good parts; what makes it popular is, at the end of the day, that it’s a page-turner.

However, when people ridicule “Twilight,” it isn’t because of the parts of the series that present a skewed reality for its readers. Most of the time, if one hates the story as intensely as a lot of people do, they probably haven’t read or watched further than the movie trailer. Even if one doesn’t have quite as strong feelings about “Twilight,” they likely have a sort of underlying condescension toward it instead.

Either way, “Twilight” isn’t the only work of literature or media targeted toward young people that is flawed. Melissa Rosenberg, screenwriter of all five “Twilight” movies, pointed out in an interview with Jezebel that the worldwide response given to the saga is quite different from the response given to similar YA stories geared to teenage boys rather than girls.

“We’ve seen more than our fair share of bad action movies, bad movies geared toward men or 13-year old boys,” Rosenberg said. “And you know, the reviews are like okay that was crappy, but a fun ride. But no one says ‘Oh my god. If you go to see this movie you’re a complete fucking idiot.’ And that’s the tone, that is the tone with which people attack Twilight.”

Meyer’s vampire romance incited a whole host of both fans and anti-fans. When “Midnight Sun,” Edward’s point of view of “Twilight,” came out in August 2020, the saga experienced a renaissance. The movies hit Netflix again in 2021, and all five of them were the most-watched movies on the streaming service. Teenage girls have the ability to skyrocket things to fame and then give them staying power, no matter the controversy; even 17 years after the first book came out, “Twilight” is still as popular as ever.