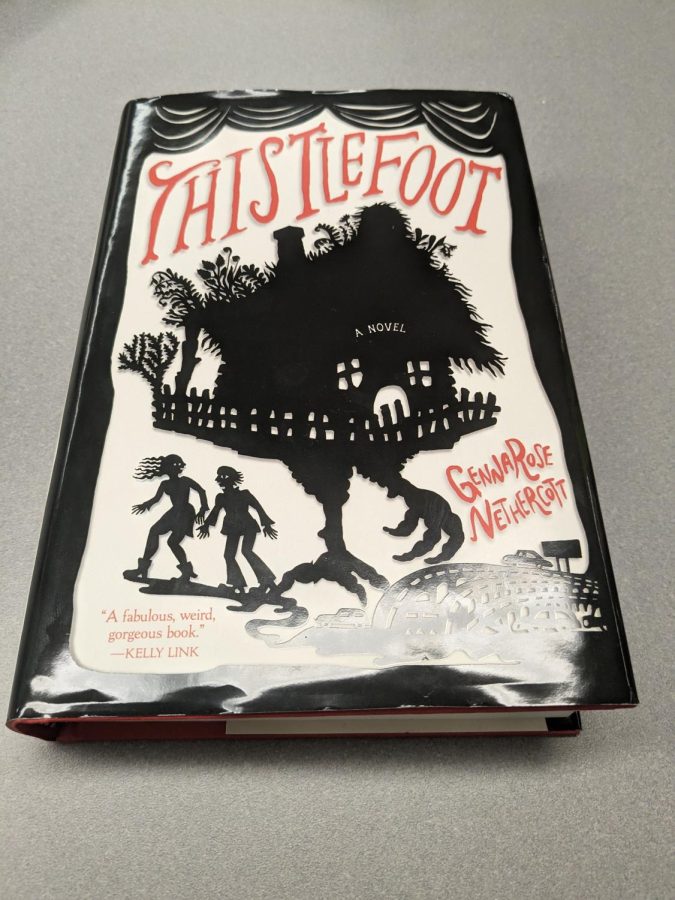

“Thistlefoot” crafts a powerful story of Jewish remembrance

February 9, 2023

In many Eastern European countries, Baba Yaga is one of many typical folkloric figures. She’s a mysterious hag, a witch who performs miracles or curses depending on who you are. Most importantly, she owns a house held aloft on the clawed legs of an enormous chicken that stalks the steppe and can take Baba Yaga anywhere.

Before reading GennaRose Nethercott’s debut novel “Thistlefoot,” released last October, I had never given the Baba Yaga myth much thought. Reading this book has forever transformed my perception of the tale. Nethercott uses the book’s 431 pages to reimagine the folktale and implant its mythos firmly into the modern day. Leaning on her own Ashkenazi Jewish roots, Nethercott has crafted a beautiful and haunting Jewish narrative of family, generational trauma and, ultimately, remembrance that resonated with my own Jewish heritage.

The protagonists of the novel are estranged siblings Bellatine and Isaac Yaga, fifth generation descendants of Baba Yaga herself, who in this world was a Jewish woman living in a shtetl, the Yiddish term for a village the Russian Empire forced Jews to live in, in what’s today central Ukraine. At the behest of an inheritance lawyer, the Yaga siblings convene at a port in New York City to receive a mysterious package from Baba Yaga: an enormous box. Out of this box stalks a century-old, crumbling shtetl house on chicken legs, a rarity, but not entirely impossible in the world of Nethercott’s novel. Isaac, ever the salesman, has an idea to revive the family business and tour the country with the house and host a puppet show. Bellatine, a carpenter, feels an odd familial pull to the unusual house, which she warmly christens “Thistlefoot,” and agrees to Isaac’s plan.

Things go south quickly. Both of the siblings possess magical abilities: Isaac an ability to mimic voices and faces perfectly, and Bellatine a power she calls the embering: through touch, she can bring inanimate objects to life. Isaac doesn’t care about his gift; Bellatine believes hers to be some ancient curse. The siblings’ relationship goes rocky as they hide or deflect their powers from each other and as they debate what to do with an eerie string of deaths that follows them across the country. A mysterious figure with a Russian accent has arrived in the U.S. and is following the siblings and Thistlefoot, using his own abilities to turn ordinary people into an army of angry, fearful drones.

As the Yagas just barely time and time again escape from the mystery villain, who is christened the Longshadow Man, they learn more about Thistlefoot’s history and its first owner, Baba Yaga. The house is the sole survivor of an antisemitic pogrom waged against Baba Yaga’s shtetl in 1919. The horror of the event twisted the fabric of reality enough to create the Longshadow Man, a demonic personification of the pogrom itself. It also sparked the embering in Baba Yaga, who used it to animate her shack into the living, thinking Thistlefoot, who escaped to allow the Yaga family and the memory of their shtetl to live another day. The Longshadow Man is stalking the Yagas and Thistlefoot to finish what he started and complete the pogrom. With this understanding, Bellatine and Isaac take it upon themselves to exorcize the Longshadow Man and ensure the memory of the Jewish community wiped out a century prior can live on.

This novel is a hauntingly beautiful examination of Jewish trauma and self-acceptance. Both siblings enter the novel estranged from themselves and their pasts, consumed with self-hatred, and exit the story with the Longshadow Man exorcized and the history of their ancestral community proudly living forevermore within them. Nethercott makes the point, subtle as a brick, that antisemitism, like any ideology obsessed with ethnic cleansing, works by not only ending lives, but also by slashing the connection current marginalized people have with their ancestry. The Longshadow Man is defeated not through Bellatine’s tremendous life-giving power. Rather it is Isaac’s remembrance of the individual Jewish lives snuffed out by Russian soldiers and mobbing farmers, denying the progrom’s goal of cultural elimination, that destroys the demon. Baba Yaga herself is a perfect example of this. Nethercott allows Thistlefoot itself to narrate many possible stories about the old hag, all prefaced that these are just that: stories. The reader traverses the book thinking that they will never know the actual origin story of Baba Yaga and Thistlefoot itself.

Finally, just shy of the novel’s boiling point, the true history of Baba Yaga is revealed: she was no witch with magic powers, and she did not eat babies or curse local merchants. She was just an ordinary Jewish woman, mother of two, who lived and died in the Pale of Settlement, haunted by the cruel destruction of her town and people.

The Jewish literary tradition is often noted for being dark, quirky and self-deprecating. Nethercott’s novel is no exception. The Yaga siblings and the cast of characters who join them on their quest are odd, flawed, funny and human. They are a treat to read, root for and question. They are perfect champions for keeping the memory of their past alive: they are not brave or heroic. They are strong though, with calloused hands that hammer mezuzot into door frames and beautiful voices that sing and shout in Yiddish. Their role in the story of Baba Yaga and the shtetl razed a hundred years ago is indeed to be their avengers, but in an extremely Jewish way. This is what gives Nethercott’s novel its candor, melancholy, and heartaching beauty. The Yagas’ task, as has been the task of countless Jews for thousands of years, is simply to ensure that their ancestors’ memories may be a blessing. And that, the nullification of the pogrom, the perseverance of my people, is the ultimate revenge to antisemites everywhere.