Ecologist, author Robin Wall Kimmerer proposes “reclaiming the grammar of animacy” at Engel-Morgan-Jardetzky Lecture

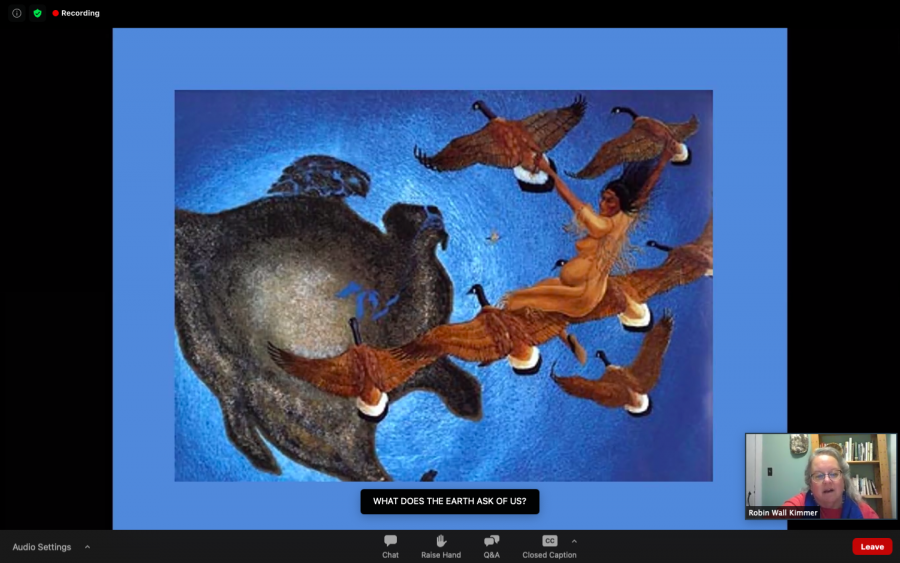

Kimmerer’s presentation included a painting of the Potawatomi origin story of Turtle Island, in which North America was formed on a turtle’s shell by many animals.

March 11, 2021

Author and professor Robin Wall Kimmerer spoke up for the human rights of land itself as a living ecosystem last Thursday, vying for a shift in perception of nature in language and policies. From Syracuse, New York, Kimmerer spoke at Macalester’s Engel-Morgan-Jardetzky Distinguished Lecture on Science, Culture and Ethics over Zoom on the topic of “restoration and reciprocity.”

Macalester biology professors Devavani Chaterjea and Mary Montgomery introduced the lecture speaker. The Engel-Morgan-Jardetzky Distinguished lecture series was founded and funded in 2001 by Oleg Jardetsky, pioneer of biological applications of nuclear magnetic resonance.

Guest speaker Kimmerer, or “light shining through sky woman” in Anishinaabeg Potawatomi, argued in her lecture to rethink the westernized ideology of land as property in favor of the Indigenous ideology of land as identity, sustainer and teacher.

“Most of our [western] institutions privilege this one view.” Kimmerer said. “[But] land is understood as the place where we enact our moral responsibility to all of life [in the Potawatomi Nation].”

Kimmerer is a Distinguished Professor at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry and an enrolled member of the Potawatomi Nation. In 2015 she addressed the general assembly of the United Nations on the topic of “Healing Our Relationship with Nature.” Kimmerer lives in Syracuse, NY and is the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment.

Her book “Gathering Moss” was awarded the John Burroughs medal for nature writing in 2005. “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants” was awarded the Sigrid Olsen nature writing award. Wall Kimmerer has also authored numerous scientific papers on plant ecology, bryophyte ecology, traditional knowledge and restoration ecology.

Kimmerer also spoke of land as a source of knowledge, a sacred healer and ancestral connection, as well as the residence of our non-human plant and animal relatives, instead of the colonialist treatment of land and ecology as capital.

“Almost all of us live in a way that we are harnessed to institutions and certainly to an economy that relentlessly asks ‘What more can we take from the earth?’” she said. “And really, the question needs to be ‘What does the earth ask of us?’ What is our responsibility in return for the gifts that come to us unbidden every day?”

In her lecture, Kimmerer proposed the theory of the “honorable harvest” for humanity’s treatment of the land and ecosystem, which proposes first asking permission and consent, only taking what you need, minimizing harm, using everything you have taken, sharing what you’ve taken and then being grateful for reciprocal gifts. Kimmerer said the theory of the honorable harvest includes cleaning up the water.

“The last of the tenants of the covenant of reciprocity is: take only that which is given,” Kimmerer said. “We need to rethink this notion of human exceptionalism and seek justice for all creation.”

Kimmerer also focused her lecture in part on how the language we use shapes and reflects our perception of the world, and proposed adding the pronouns “ki” and “kin” (plural) to English for plants and animals instead of using the term “it.” Kimmerer said this pronoun change would support traditional Indigenous knowledge, scientific knowledge and the knowledge of plants themselves.

“How might we give healing and medicine to the English language so we don’t have to ‘it’ our beloved relatives?” Kimmerer said. “[Mother Nature’s] gift or natural resource: words matter. I don’t think we need words and a worldview that destroys beings that sustain us.”

Kimmerer gave several non-Indigenous definitions of sustainability she has encountered in science in the U.S., including “developments that seek to produce sustainable economic growth while ensuring future generations’ ability to do the same by not exceeding the regenerative capacity of nature,” as it read in her presentation. Kimmerer said her native elders did not agree with this westernized scientific view of sustainability.

“In fact, what they said is, ‘It sounds to me like they just want to keep on taking,’” Kimmerer said. “When your feet hit the ground in the morning, we should be thinking ‘what can we give?’”

Kimmerer said, “We should not be just takers of the world. What does the world ask of us? Respect. Gifts and responsibilities [are] two sides of the same coin.”

Kimmerer asked her question, “What does the world ask of us?” throughout the lecture and answered it with traditional Indigenous storytelling. She told the Potawatomi origin story of Turtle Island, or North America, in which Skywoman fell through a hole in the sky made by the fallen tree of life and was saved by the geese and other animals that fell with her. They brought her mud and earth from below the vast ocean that they then planted on the back of the turtle. The muskrat gave his life to get Skywoman earth from below the water for planting. Kimmerer said the gratitude and reciprocity of humans and creatures formed the world.

“From the branch in her hand, the tree of life, she seeded that land with all the seeds of all of the plants,” Kimmerer said. “And so, we know that the world was created not by one alone. In the beginning of the world the other species were our life raft. And now in the spirit of reciprocity we must be there. This is the way we answer the question, “What does the earth ask of us? In return for the gift of this world on Turtle’s back, what is it that we can give in return?”

Kimmerer also talked about the Indigenous “one bowl one spoon” ethical model of sustainability to preserve natural resources more effectively. The thousands year old Indigenous metaphor is based on equitable shared practice for hunting grounds and resources. The one bowl is used among many different nations, and resources are finite. The one spoon signifies that all Peoples are expected to limit their consumption for the continued abundance of the hunting grounds in the future.

Kimmerer talked about changing U.S. and Indigenous legal frameworks to align with the natural laws of earth, challenging the idea that earth’s living systems are our property.

“The rights of nature simply say that nature, in all its forms, has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles,” Kimmerer said.

Kimmerer gave examples of Ecuadorian law, in which the land can take people to court, as well as a river in the South Island of New Zealand that is enshrined with human rights in Maori law.

“International tribunals [are] building rights of case law for the protection of the systems who keep us alive,” Kimmerer said.

Kimmerer ended with an analogy in the Potawatomi language of the prefix “mni,” as in Minnesota.

“In our Potawatomi language, the word [mni] for ‘berry’ and the word ‘to give’ mean the same. [The language] asks us to be like the berries.”

Macalester Biology professor Robin Shields-Cutler read Kimmerer’s book “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants” with other biology department members in preparation for the lecture. Shields-Cutler wrote in an email to The Mac Weekly that he related to Kimmerer’s writing through his own experiences as a father, gardener and microbiome researcher. Shields-Cutler wrote that Kimmerer’s work helped him view reciprocity to the earth as familial.

“Her discussions of the “honorable harvest” and the effects on ecosystems from rampant extraction of resources are incredibly relevant.” Shields-Cutler wrote. “There are many languages lost in our society, and one of those, I feel, is the interest and skill to respectfully create, repair, and reuse.”

Shields-Cutler also related to Kimmerer’s negative depiction of western cultures that reward cheap and disposable labor in capitalist consumer market economies. Shields-Cutler wrote that the direct ongoing link of these destructive forces to colonialism, white male dominance and the rigid, westernized pillars that define science in America was very thought-provoking.

“Dr. Kimmerer’s book helped me see these challenges in a larger systemic structure and shared ways of thinking that can provide intentionality to the choices we make.”