Lack of mental health training leaves professors, students wanting more help

April 8, 2018

Content Warning: Matias Sosa-Wheelock’s death affected all members of the campus community differently, depending on individual experiences that night, in the days following or with mental health and mental healthcare at other points in their lives. This special report includes in-depth reporting on the response to Sosa-Wheelock’s death as well as the state of mental health and healthcare on campus more broadly. While we have refrained from including graphic details, it may nonetheless be difficult to read. Before beginning, please be aware.

For a list of support resources on and off campus, visit this page.

Managing academics amidst difficulties with mental health requires what can sometimes be an unexpectedly complex set of relations between students and faculty.

One frequent point of contact between students and professors regarding these issues is requests for extensions on coursework. International studies professor James von Geldern’s approach to granting extensions, which has long been strict, may be evolving.

“If I’ve assigned something a month before, [and the student] comes in a few days before saying, you know, ‘I’m having anxiety issues. I need an extension.’ You know, no, there’s a system. You need to follow the system,” he said. “But increasingly over the last few years I’ve found myself being lenient on extensions.”

Students have mixed views on how their professors handle mental health concerns.

Voices on Mental Health co-chair Leah Wilcox ’18 commented that sensitive content in some of her courses that could have been approached more mindfully. “Like, when we’re talking about psych disorders, don’t talk about them like no one in the room has the psych disorder. Oh my God. I see this most often with eating disorders, actually. [Professors will] talk about eating disorders and how hard it is to get people to eat, stuff like that, and then there’ll be three people in the room flinching.”

“I think most professors do a good job, at least the ones that I’ve had, of being lenient and just listening to what’s going on and being understanding about it,” Anni Clark ’21, a domestic abuse and sexual violence survivor, said. “That should be encouraged.”

“I know a lot of people who are timid or don’t know how a professor will react or how to go about approaching [asking for help],” they continued. “In my experience, with myself and with people close to me, you can’t help them if they don’t want to be helped, so I feel like there’s a limit to what a professor can do.”

Though professors can’t be expected to do everything, their jobs position them to serve as a resource for struggling students – whether that be in developing closer personal relationships or directing students to other campus resources when it is appropriate to do so.

Onur Unal ’18, a student from Sinop, Turkey, has taken multiple semesters off for his mental health. “I failed a course in the economics department [and my] professor, before I failed the course, want[ed] to meet with me and he asked, ‘What’s going on?’ And I told him and he said, ‘You should go to the Health and Wellness Center and talk to a counselor,’” Unal said. “[That] was the start of my journey for treatment.”

“The faculty is at the frontline of this. They’re the ones who see the students regularly. They’re the ones who notice their students coming to class,” Provost and Dean of the Faculty Karine Moe said.

Despite their role on the front lines of student life, Macalester professors are often unequipped to do the work of identifying and helping students struggling with their mental health. In the current mental health climate, that unpreparedness is having serious consequences.

“We really don’t [have any required faculty training],” Vice President for Student Affairs Donna Lee said, “And I’m not sure how I feel about actually making it mandatory. What I will say though is that I’m seeing an increase in the number of faculty and staff for that case who want training and education.”

“We get some information about what to do, and most of it’s sort of ‘call this office,’” biology professor Devavani Chatterjea said. “But given that these students are… in our world on a regular basis, it’s not just sort of calling someone to help manage a crisis, but knowing what might be good strategies, how we might be most useful to them, what you can ask of students and what you can give them.”

As faculty members express a desire for greater training in helping students address their mental health, Macalester administration has been thinking about how best to expand these options.

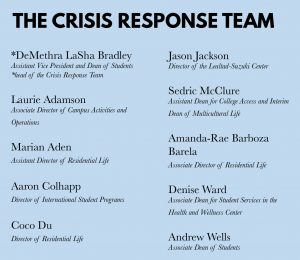

“My hope is that we engage this issue as a community, in a holistic, collaborative and integrated way that extends resources and support beyond the Health and Wellness Center to other parts of our campus community,” Lee wrote in an email to The Mac Weekly. “I’m committed to creating spaces, or even enhancing the spaces that we’ve already created on our campus to continue to have those conversations. This should not be a one and done,” Assistant Vice President and Dean of Students DeMethra LaSha Bradley said.

There are, for the college, opportunities to provide willing professors with further training than they have received in years past.

Executive Director of the Minnesota Branch of National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Sue Abderholden ’76 has provided area schools like Carleton College and the University of St. Thomas with mental health first aid and training. The full course lasts eight hours.

K-12 teachers at Minnesota public schools are required by law to take part in mental health training and 2016 Minnesota Session Laws state a new five year teacher license renewal condition for an additional hour of evidence-based suicide prevention training. This training involves Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR), which is an hour long session that NAMI offers. Professors, at private or public institutions, are not included under this law.

“[Macalester] should have it so all the faculty get QPR. We can come in and do that so that they know how to respond and that would make perfect sense for [professors] to have that,” Abderholden said.

Voices on Mental Health co-chair Tess Huber ’18 has gone through both mental health first aid and QPR training and is adamant about bringing these trainings to campus. “Even though I’ve been studying mental illness for a while, I feel so much more able to work with someone experiencing psychosis and things like that [now]… I think [mental health first aid] should be required for everyone on campus,” she said.

While those trainings cost money for most colleges, Abderholden mentioned the possibility of doing a series of pro bono sessions at Macalester to begin the process of bolstering the college’s mental health training program for professors.

Moe is open to the idea, but said that initiating a training of this sort falls, at least in part, under the jurisdiction of Student Affairs.

“I think that it would likely be something we would do in concert with Student Affairs since they are really the professionals around these issues,” she said. “I would really rely on the judgment of the Student Affairs staff to help me think about what would be the best way to do that.”

Although mental health has been on the minds of faculty and staff, Matias Sosa-Wheelock’s death in February spurred more conversations focused on faculty training.

“Part of the communication [that Karine sent to faculty] was something that Ted [Rueff, Director of Counseling] had written for her that talked about how to manage the classroom, how to talk about it, how to help students process [Matias’ death],” Lee said.

The Jan Serie Center for Scholarship and Teaching provides weekly Talking About Teaching sessions covering different topics relating to teaching and scholarship. Although these often don’t relate to mental health, after February’s events, political science professor and Director of the Serie Center Adrienne Christiansen arranged a few discussions and panels through the center to voluntarily bring faculty voices together on these pressing topics.

Notably, professor and chair of the psychology department Joan Ostrove hosted one on the Friday following Matias’ death and Chaplain Kelly Stone, Director of Academic Programs and Advising Ann Minnick and Rueff hosted one the next Monday. Those conversations were well attended and received. Additionally, the Faculty Advisory Council has also discussed how to better educate faculty, set appropriate expectations for students and work better with institutions like Disabilities Services to provide the support students need.

Another opportunity for faculty to receive training on mental health issues, highlighted by political science professor Lisa Mueller, is through Macalester’s Allies Project.

“It’s not specific to mental health concerns but I think many of the tenets [of the Allies Project] training apply,” Mueller said.

“For example, one of [the] philosophies on the Allies Project at Macalester is that allyship is not a badge that you wear or a peak that you reach, but allyship is an ongoing process,” she continued. “I think that’s a very humane way to approach allyship – whether we’re trying to approach it with communities of color or with different mental health concerns.”

Apart from these few conversations, Mueller feels largely unprepared to help her students deal with their mental struggles – but knows she cannot let that stop her.

“I have felt more comfort in revealing my struggle with my students because I feel like I didn’t really have a choice,” Mueller said. “Like, here’s this task that I need to meet of supporting students with varying degrees of mental health concerns. I am inadequate to the task, but it’s my responsibility and I don’t have a choice but to step up to the plate.”

“Through my experiences, I have learned that my professors have a lot to learn from me as to how they can be there for their students,” Malvika Shankar ’19, who is currently on a voluntary leave of absence from Macalester, said. “While some professors are great, some only look through the lens of establishing equal and fair measures amongst the students of their class, and this is unfair when students are inherently ‘unequal’ in various factors.”

More honesty from professors about their own mental health challenges could open up those kinds of connections as well.

“I want to be forthright about my struggle,” Mueller said. “[Mental health is] really difficult to address, and I think something that I share in common with many Macalester students [is that] I tend to want to disguise my struggle and always want to appear with it and together.”

On multiple occasions, Mueller referred to an opinion piece written by Hannah Gray ’18 published in the March 9 edition of The Mac Weekly titled “Macalester is Not OK” as a touchstone of sorts.

“The reason why I appreciated Hannah’s article so much is that she includes us all, the experts and non experts, in this collective responsibility to support one another,” Mueller said. “That was so liberating and empowering for me.”

“It was the first time that I realized, you know, I don’t have to be a professional counselor to provide some support for these students,” she continued. “And if we treat each other with humanity, then there is some space for me to mess up as long as I’m acting in good faith and trying to be a better ally.”