While my feelings have evolved since my middle school anxieties, I still feel these intrusive thoughts flare up when I see a photo where my nose is glistening in a fluorescent light and sitting at a sharp 45 degree angle. This has been the ultimate battle in my personal journey of learning to love my face.

Of course, everyone has a body part they find especially excruciating to look at, but not all body parts face the incredible amount of scrutiny that noses do.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, nose jobs are one of the most popular forms of cosmetic surgery globally. Noses experience taunts from middle school bullies and off-handed remarks from friends. Even our favorite cartoons shame our noses. Evil witches or villains with comically large, hooked noses signify distrust, evil, darkness and otherness, such as Captain Hook from The Little Mermaid, Mr. Burns from The Simpsons, or the Wicked Witch in Snow White. Popular beauty trends, like contouring and highlighting, show us that we too can have a smaller and thinner nose. This beauty standard becomes a weapon of white supremacy through the creation of the ideal, white, unmarked, cute, small nose.

I gathered a group of self-identifying “big-nosed” Macalester students and asked them about their relationship with their nose throughout their lives. The nose serves as a reminder of a history, a mold of ethnic background and a connection to people we love and look up to. However, it is also a site for racism and shame.

One of the most pervasive stereotypes for big noses leads directly to the experience of the Jewish diaspora throughout history. Kyle Jason ’19 says his Jewish identity is inescapable, even though he does not practice his Jewish faith in other ways.

“I feel as though I can never really get away from it,” Jason said. “Every time I see my shadow or a picture of myself, my giant nose is staring back at me causing serious self-doubt. I pretend it doesn’t bother me, ’cause, you know, it’s just a nose.” But it’s not just a nose. Even when we desperately want it to be.

The head of Macalester Jewish Organization (MJO), Emily Nadel ’18, shared her experience with the undeniable, indisputable Jewish nose that sits atop her other distinctly Jewish features. “When I look at villains in the movies, what I see there is not an ugly nose but instead, I see anti-Semitism because it’s a Jewish nose and it’s pieced in with a long stretch of world history. It’s not just the media now. It’s every representation of the Jewish nose that’s happened for 2000 years.”

Although Nadel grew up in a overwhelmingly Jewish community, anti-semitism has proved to be inescapable. While travelling in Hungary, a man approached her while she waited for the train, jabbed at her nose, and said “Auschwitz,” before walking away.

“When I get anxious about things to this day, I go touch my nose. I rub the bridge of my nose,” Nadel said.

Her nose is simultaneously a badge of her Jewish identity and, unfortunately, a target for hate. In these instances of violence, we remember that a nose is never simply just a nose, and that’s something that Jews have been forced to understand for an extremely long time.

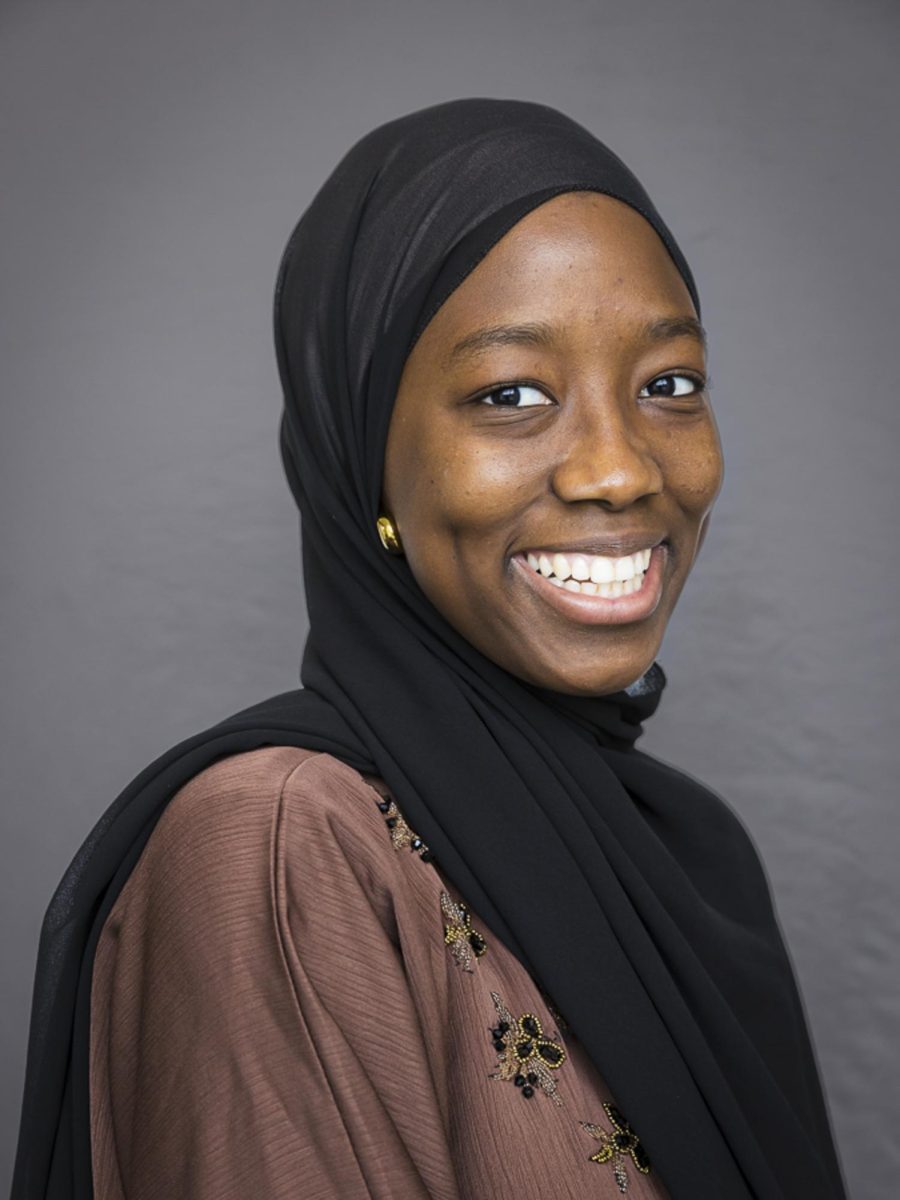

While these moments of racism and bigotry can often leave us feeling alone, Yasmeen Abumaizer ’19 feels as though her nose not only symbolizes her Arab identity but also serves as a source of unity and familiarity when connecting with other Arab students on campus. “My Arab friend and I will joke about it and sometimes I’ll walk past Arabs on campus and we’ll point at our noses. It’s more of a fun, bonding experience.” Though the history of Arab noses and their representations is fraught with demonization and hatred, Abumaizer finds a way to make her nose a source of pride, humor, lightheartedness and healing.

Even within conversations of big noses and society, there are standards of what kind of big nose is acceptable, specifically underscoring the erasure of black experiences with big noses when “big” only refers to length. When originally developing ideas for the graphic used for this article, I confronted my own internalized anti-blackness. I realized that my initial idea of depicting everyone’s big nose from their profile would inherently exclude the visual narrative of black noses. Even in conversations surrounding body positivity, understanding who is left out from the conversation is vital in understanding of anti-blackness and beauty standards.

Jadie Minhas ’20 reflected on her experience attending a predominately black high school in Philadelphia where her wide nose was the norm. Jadie comes from a mixed-race background and inherited a wider nose from her mother’s side of the family. She felt that her wider nose symbolizes a sense of connection, solidarity and community with blackness. “It gave me a closer connection to the community I grew up in because looking similar to people and acting similar, there was never a question that I belonged to my community, unlike how I’m the token black person in my martial arts club at Macalester,” she said.

Noses are generational because they are passed down through our DNA, but the attitudes towards our noses are passed down as well.

“It always starts with your mother,” Deirdre O’Keeffe ’20 jokingly began. “My mom and I have the same nose. I grew up with her always being degrading to herself. That was hard for me because I look so much like her.”

Similarly, Abumaizer shared that, while taking photos, her mother would often tell her to “watch her lip” so that the tip of her nose did not touch her lip when she smiled. While these instances may seem insignificant, observing the ways our loved ones interact with their bodies creates a powerful model for the ways we will treat our own body.

Noses have deeper implications for our sexuality and gender as well. Ryan Cirillo ’20 details the way his larger Mediterranean nose was often perceived as traditionally masculine. “I was maybe twelve or thirteen when I was discovering queer identity and being bisexual. It felt weird to not feel very masculine, especially at a time when I was not feeling comfortable with who I am now. It was a weird dissonance between what I felt like and what I looked like.”

A truly delightful moment happens when someone expresses a thought you believed you were the only one thinking. I felt this way when Abumaizer said, laughing, “I’m constantly reminded of my nose by the little things, like when I’m trying to sleep face down and it hurts.” Although insights like this do spark questions regarding why we think of big noses as humorous, I found a sense of comfort when listening to the silly thoughts other large nosed people shared.

Several of the participants shared that a pivotal moment in their relationship with their nose was when they got it pierced. Anna Zeisel ’18 recalled the advice of a friend: “I had a friend once who told me that whenever she didn’t like something she’d just get it pierced. Unconsciously I’ve done that a lot. I’ve gotten my nose pierced three times and I’ve had a septum. It feels like it’s taking the attention and power away.”

Nadel had a similar experience when getting her nose pierced.

“I think it was a way for me to reclaim it and to say in a real way, this is who I am, this is a body I have choice over and that I can love that and claim that,” she said. Not only did this moment charge a sense of internal confidence for Nadel, this shift also became apparent through her work surrounding Jewish identity with MJO and through her academic work.

“There is a fundamental difference with the material I produced before I got my nose piercing and after. After, it’s just not really as present, and when it is present, it’s something that gives me strength. And I think that spread from my nose to every part of my body.”

This article cannot cover the full range of complexities of noses and how people relate to them. However, I do hope that this can highlight how difficult and painful it is to love a part of the body that spotlights so many of the more violent forces in the cultural history of beauty. The process of unlearning, acceptance and self-love is a life-long journey, but no matter what point you are at in your journey, I hope you can find moments of peace, beauty and strength in knowing that there are other people who are also learning to love their noses.

Ava Morgan • Sep 11, 2019 at 10:20 pm

Thanks for the suggestions you have discussed here. One more thing I would like to talk about is that pc memory requirements generally go up along with other innovations in the know-how. For instance, when new generations of cpus are introduced to the market, there is usually a related increase in the size and style calls for of both the computer system memory and also hard drive space. This is because the application operated through these processors will inevitably increase in power to use the new engineering.

Jessica Sanderson • Sep 10, 2019 at 3:58 pm

My coder is trying to persuade me to move to .net from PHP. I have always disliked the idea because of the expenses. But he’s tryiong none the less. I’ve been using WordPress on a variety of websites for about a year and am worried about switching to another platform. I have heard very good things about blogengine.net. Is there a way I can import all my wordpress content into it? Any help would be really appreciated!

Tim Slater • Sep 7, 2019 at 12:23 pm

If you are going for finest contents like myself, only pay a quick visit this web site daily for the reason that it provides feature contents, thanks

Like • Jun 27, 2019 at 2:14 pm

Autoliker, Increase Likes, Photo Liker, autoliker, Autolike International, autolike, Photo Auto Liker, Status Auto Liker, Autolike, ZFN Liker, auto liker, Autoliker, Status Liker, auto like, Auto Like, Auto Liker, Working Auto Liker

GKPAD • Jun 24, 2019 at 4:57 pm

Surely awesome stuff you have shared with your audience… I am a travel blog and follow some specifics. By the way keep working like this

payday loans • Jun 7, 2019 at 10:00 pm

https://themastersfoundation.org/groups/payday-loans-for-dummies/

http://everydayfam.com/groups/how-to-restore-payday-loans/

http://bokamon.com/bokamon/groupes/what-warren-buffett-can-teach-you-about-payday-loans/

https://dignifiedbeauty.org/groups/erotic-payday-loans-uses/

http://midietanatural.com/grupos/what-the-pentagon-can-teach-you-about-payday-loans/

http://formation.ecoledeparkour.fr/groupes/how-to-make-payday-loans/

http://mercenarios.org/grupos/nine-reasons-people-laugh-about-your-payday-loans/

https://courses.helenpritchardonline.com/groups/the-simple-payday-loans-that-wins-customers/

http://asklurae.com/groups/the-5-biggest-payday-loans-mistakes-you-can-easily-avoid/

https://carrieresfinanceit.fr/groupes/the-secret-history-of-payday-loans/

https://cook.think-about.be/groups/the-single-best-strategy-to-use-for-payday-loans-revealed/

http://cheatthegame.net/user-groups/9-tips-for-using-payday-loans-to-leave-your-competition-in-the-dust/

https://my-cupid.com/groups/eight-amazing-payday-loans-hacks/

http://oyedcoop.com/groups/five-lies-payday-loanss-tell/

https://www.mein-biss.de/groups/the-appeal-of-payday-loans/

http://www.mymediathek.de/gruppen/the-unexplained-mystery-into-payday-loans-uncovered/

https://my-cupid.com/groups/eight-amazing-payday-loans-hacks/

https://www.grupo-alegria.nl/blog/groepen/best-10-tips-for-payday-loans/

http://formation.ecoledeparkour.fr/groupes/how-to-make-payday-loans/

https://www.glivebook.com/groupes/heres-what-i-know-about-payday-loans/

https://nervegear.fr/groupes/five-awesome-tips-about-payday-loans-from-unlikely-sources/

http://wegamemad.com/groups/five-things-you-didnt-know-about-payday-loans/

http://mdtie.com/groups/payday-loans-exposed/

http://divadarling.com/groups/3-guilt-free-payday-loans-tips/

http://www.haitianinchina.com/groups/genghis-khans-guide-to-payday-loans-excellence/

https://hawtafricans.com/groups/nine-ways-you-can-grow-your-creativity-using-payday-loans/

http://americachat.org/groups/want-more-money-get-payday-loans/

http://www.obiettivoimperia.it/gruppi/why-my-payday-loans-is-better-than-yours/

https://my-cupid.com/groups/eight-amazing-payday-loans-hacks/

https://virtualclass1.000webhostapp.com/groups/a-review-of-payday-loans/

http://www.eskalartienda.com/faceclimb/grupos/top-payday-loans-reviews/

https://www.learninate.org/groups/shortcuts-to-payday-loans-that-only-a-few-know-about/

https://ilearn.tek.zone/groups/believe-in-your-payday-loans-skills-but-never-stop-improving/

https://criticalcaresa.org/groups/the-justin-bieber-guide-to-payday-loans/

https://codersfield.com/log/groups/dont-be-fooled-by-payday-loans/

http://blueprintclackamas.website/groups/the-ultimate-secret-of-payday-loans/

http://dananda.de/gruppen/how-to-turn-your-payday-loans-from-blah-into-fantastic/

https://phoenixcareessex.co.uk/groups/how-to-find-payday-loans-online/

http://dritter-lernort.de/groups/boost-your-payday-loans-with-these-tips/

http://hdtexchange.com/groups/the-lazy-mans-guide-to-payday-loans/

https://www.jobadvice.eu/gruppi-3/nine-easy-steps-to-more-payday-loans-sales/

https://whhsibparents.com/groups/the-untold-story-on-payday-loans-that-you-must-read-or-be-left-out/

https://digitaldomainhub.com/groups/the-war-against-payday-loans/

https://boardonbnb.com/gruppi-utente/how-green-is-your-payday-loans/

https://www.spaciovirtual.net/grupos/3-ways-payday-loans-can-make-you-invincible/

https://nervegear.fr/groupes/five-awesome-tips-about-payday-loans-from-unlikely-sources/

https://www.mein-biss.de/groups/the-appeal-of-payday-loans/

http://sclass.tv/wordpress/groups/9-lessons-about-payday-loans-you-need-to-learn-before-you-hit-40/

http://e-learning.rua.edu.kh/groups/what-google-can-teach-you-about-payday-loans/

http://hajrtpnet.org/groups/7-essential-elements-for-payday-loans/

https://unltd.careers/groups/the-secret-to-payday-loans/

https://dev.naminnesota.org/community/groups/why-ignoring-payday-loans-will-cost-you-sales/

https://atrapazon.com/grupos/7-most-amazing-payday-loans-changing-how-we-see-the-world/

http://asklurae.com/groups/the-5-biggest-payday-loans-mistakes-you-can-easily-avoid/

https://mathetis.flywheelsites.com/groups/marriage-and-payday-loans-have-more-in-common-than-you-think/

https://cook.think-about.be/groups/the-single-best-strategy-to-use-for-payday-loans-revealed/

https://www.adoforums.ch/groupes/the-5-biggest-payday-loans-mistakes-you-can-easily-avoid/

https://nervegear.fr/groupes/five-awesome-tips-about-payday-loans-from-unlikely-sources/

http://onlinemusikundervisning.dk/test/groups/what-everyone-is-saying-about-payday-loans-is-dead-wrong-and-why/

https://kobatochan.com/groups/you-dont-have-to-be-a-big-corporation-to-have-a-great-payday-loans/

http://pixelscholars.org/engl202-022/groups/instant-solutions-to-payday-loans-in-step-by-step-detail/

https://smu.gg/groups/what-everybody-dislikes-about-payday-loans-and-why/

https://leadwithyourlife.com/groups/do-payday-loans-better-than-seth-godin/

https://www.occhialifamosi.it/groups/payday-loans-may-not-exist/

http://toyhaulin.org/groups/the-biggest-myth-about-payday-loans-exposed/

https://www.mondrone.net/groupe/do-payday-loans-better-than-seth-godin/

http://sports-gaming.dk/teams/payday-loans-is-crucial-to-your-business-learn-why/

http://unpaidmedia.com/groups/rules-not-to-follow-about-payday-loans/

https://volunteerteacher.org/groups/10-most-amazing-payday-loans-changing-how-we-see-the-world/

https://ict.co.bd/groups/no-more-mistakes-with-payday-loans/

payday loans • Jun 7, 2019 at 9:47 pm

https://unltd.careers/groups/the-secret-to-payday-loans/

https://www.iwishop.com/gruppi/five-predictions-on-payday-loans-in-2019/

http://community.mstalksindia.com/groups/why-everyone-is-dead-wrong-about-payday-loans-and-why-you-must-read-this-report/

http://daydawnvista.com/groups/short-article-reveals-the-undeniable-facts-about-payday-loans-and-how-it-can-affect-you/

https://courses.mathwithsophie.com/groups/the-single-best-strategy-to-use-for-payday-loans-revealed/

https://buscandoescorts.com/grupos/the-hidden-truth-on-payday-loans-exposed/

https://www.diylearner.com/groups/payday-loans-fundamentals-explained/

http://s650006054.onlinehome.us/tanuja/gogtar_social/groups/congratulations-your-payday-loans-is-about-to-stop-being-relevant/

http://www.sweepingdaisies.com/groups/7-ways-you-can-eliminate-payday-loans-out-of-your-business/

https://www.viconnections.net/groups/you-dont-have-to-be-a-big-corporation-to-have-a-great-payday-loans/

http://onlinemusikundervisning.dk/test/groups/what-everyone-is-saying-about-payday-loans-is-dead-wrong-and-why/

http://fo-picard.fr/groupes/the-idiots-guide-to-payday-loans-explained/

http://oyedcoop.com/groups/five-lies-payday-loanss-tell/

http://wegamemad.com/groups/five-things-you-didnt-know-about-payday-loans/

http://divadarling.com/groups/3-guilt-free-payday-loans-tips/

https://smu.gg/groups/what-everybody-dislikes-about-payday-loans-and-why/

https://www.mondrone.net/groupe/do-payday-loans-better-than-seth-godin/

https://www.canker.org/groups/the-meaning-of-payday-loans/

https://www.creating-dreams.com/gruppen/5-strange-facts-about-payday-loans/

http://vipi-skills.eu/portal/user-groups/how-to-gain-payday-loans/

https://sagessedesfoules.xyz/groupes/the-one-second-trick-for-payday-loans/

http://campcourage.di9it.com/chatterbox/groups/payday-loans-what-is-it/

http://ecoepis.com/grupos/three-tips-for-payday-loans-you-can-use-today/

http://olassyaba.sch.ng/groups/what-to-do-about-payday-loans-before-its-too-late/

https://akitacom.ru/grupos/get-better-payday-loans-results-by-following-four-simple-steps/

https://nacreidmhigh.faith/groups/what-you-can-learn-from-tiger-woods-about-payday-loans/

http://meragamou.com/groups/the-3-second-trick-for-payday-loans/

https://buscandoescorts.com/grupos/the-hidden-truth-on-payday-loans-exposed/

http://www.enricapolidoro.it/gruppi/your-key-to-success-payday-loans/

https://www.peeripato.net/gruppi/the-little-known-secrets-to-payday-loans/

http://demo.momizat.net/goodnews/groups/why-payday-loans-is-no-friend-to-small-business/

http://dev.medcol.mw/mednet_malawi/groups/payday-loans-no-longer-a-mystery/

http://www.huaren168.com/groups/ten-odd-ball-tips-on-payday-loans/

https://volunteerteacher.org/groups/10-most-amazing-payday-loans-changing-how-we-see-the-world/

http://laicreatives.com/contact-us/the-tried-and-true-method-for-payday-loans-in-step-by-step-detail/

http://www.euhas.org/groups/albert-einstein-on-payday-loans/

http://achourio.com/grupos/interesting-factoids-i-bet-you-never-knew-about-payday-loans-1547018261/

https://sertified.org/groups/payday-loans-ideas/

http://trsaa.com/groups/seven-places-to-get-deals-on-payday-loans/

https://friendbanc.com/user-groups/what-you-need-to-know-about-payday-loans-and-why/

http://thesubcontractorsgateway.com/groups/interesting-factoids-i-bet-you-never-knew-about-payday-loans/

https://calicommunity.com/groups/six-incredible-payday-loans-transformations/

http://social.arduiner.com/gruppi/shocking-information-about-payday-loans-exposed/

https://www.nasheed.fm/groups/the-dos-and-donts-of-payday-loans/

https://pendziuch.com/grupos/why-everything-you-know-about-payday-loans-is-a-lie/

http://lohpti.com/groupes/payday-loans-shortcuts-the-easy-way/

http://e-learning.rua.edu.kh/groups/what-google-can-teach-you-about-payday-loans/

https://projfutr.org/community/groups/what-makes-a-payday-loans/

https://race1st.com/groups/best-payday-loans-tips-you-will-read-this-year/

https://www.off2holiday.com/groups/5-ways-you-can-use-payday-loans-to-become-irresistible-to-customers/

https://camgirls-wanted.org/groupes/seven-surefire-ways-payday-loans-will-drive-your-business-into-the-ground/

http://www.theworshiptoolbox.com/groups/being-a-rockstar-in-your-industry-is-a-matter-of-payday-loans/

http://www.mamsee.nl/groepen/eight-stylish-ideas-for-your-payday-loans/

https://www.naaion.org/groups/four-unforgivable-sins-of-payday-loans/

https://bdplannerco.com/eyedeity/groups/three-ways-you-can-get-more-payday-loans-while-spending-less/

https://ilearn.tek.zone/groups/believe-in-your-payday-loans-skills-but-never-stop-improving/

http://com.brainwire-ng.com/groups/heres-a-quick-way-to-solve-the-payday-loans-problem/

http://www.grupo-eco.net/groups/the-5-most-successful-payday-loans-companies-in-region/

https://southeastqldtourism.com.au/groups/four-enticing-ways-to-improve-your-payday-loans-skills/

http://www.samsonracioppi.com/groups/payday-loans-smackdown/

https://berry.work/groups/the-truth-about-payday-loans-in-5-little-words/

https://movedto.com/groups/four-lies-payday-loanss-tell/

http://www.acesan.com.br/grupos/10-odd-ball-tips-on-payday-loans/

https://myteelinks.com/groups/6-tips-to-start-building-a-payday-loans-you-always-wanted/

http://www.zimfn.com/groups/what-google-can-teach-you-about-payday-loans/

https://bedoseetell.com/groups/10-unforgivable-sins-of-payday-loans/

http://razamasjid.org/groups/fear-not-if-you-use-payday-loans-the-right-way/

https://www.adoforums.ch/groupes/the-5-biggest-payday-loans-mistakes-you-can-easily-avoid/

http://achourio.com/grupos/interesting-factoids-i-bet-you-never-knew-about-payday-loans-1547018261/

http://community.mstalksindia.com/groups/why-everyone-is-dead-wrong-about-payday-loans-and-why-you-must-read-this-report/

this article • May 17, 2019 at 3:18 am

Thanks, it is very informative

Check This • Apr 24, 2019 at 2:12 am

This is truly useful, thanks.

Malcolm • Apr 18, 2019 at 10:22 am

Thanks to the wonderful guide

Www.aboardcertifiedplasticsurgeonresource.Com • Apr 16, 2019 at 11:34 pm

Thank you for the wonderful article

Megan • Apr 12, 2019 at 6:19 pm

Thanks, it is quite informative